Putting your game design through many playtests is essential to developing an amazing game. But how do you know you’re done with the game design? More specifically, how do you know when you have the right game mechanics and are ready to pitch it to a publisher or commission some art in preparation for a Kickstarter? That’s a challenging question even for experienced game designers. Here are 6 tips to help you know if you’re done with your game design and ready to move forward.

1. When You Achieve Your Game Design Vision

Whenever I start on a new game design, I grab a blank notebook and write my vision for the game on the first page. My vision statement usually includes theme, number of players, components, main mechanic, and gameplay time. My vision statement may also include other attributes that interest me, such as price point and box size. Here’s an example:

Villianopolis – a dice and card game about supervillains fighting each other for dominance in a city. This game will be for 6 players and last about an hour. During gameplay, villains will recruit henchmen/minions and research super weapons. Combat between villains will be resolved by dice. The game should cost no more than $25.

This vision should serve you more as a guide than a hard requirement. You’ll be making dozens of design decisions as you develop your game. Using your vision statement is a great way to ensure all those decisions are working towards a common goal. You’ll also likely be confronted with tempting components like custom dice or intriguing mechanics like deck building. Having a vision will keep you from constantly chasing “shiny new objects” through development.

Whenever I talk to new designers about using a Vision Statement, they usually ask me, “But what if I change my mind?”

You can absolutely change your vision statement. But you don’t want to change it on a whim. The real trick is to create some kind of process to review those changes. Maybe you can review your vision statement after 10 or more playtests. You could also list all the pros and cons of making the change you want.

2. When Your Game Has a Great Interest Curve

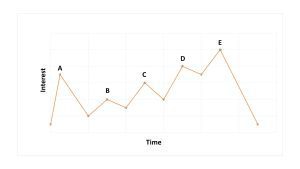

One of my all-time favorite game design books is called “The Art of Game Design” by Jesse Schnell. It is a book primarily about video game design but much of it is applicable to tabletop game design as well. Chapter 16 in the book is titled “Experience can be judged by their interest curves,” where Schnell introduces the idea of interest curves. It’s basically a graphic representation of players’ interest level through time during gameplay. Below (Figure 1) is an example interest curve for a tabletop game.

Figure 1. Interest Curve for a Tabletop Game

The graph shows in this notional game the players’ interest immediately spikes high at point A. This game has a few areas of high interest throughout the game as shown in points B, C, and D. Interest gradually rises overall during the middle portion of the game, then hits its peak at point E during the climax of the game. Keep in mind that this graph is not based on any specific numbers. You are judging the “feel” of the game. A game that feels like it has a high interest point at the beginning, several gradually increasing interest points in the middle, and a high interest point at the end has an ideal interest curve.

To see if your game has this kind of interest curve, review your game design, then evaluate the most interesting points of your game and when they should theoretically occur during gameplay. Ideally, when you make a rough drawing of these interest points, you should have something like the idealized interest curve in the figure above when your game design is nearly complete.

Another way to judge your game’s interest curve is to ask your playtesters about the most memorable moments of the game and when they occurred. You know you’re near the end of your game design when you have high interest in the beginning, a few spots of interest in the middle, and the highest interest at the end of the game.

3. When Playtesters Want to Play More Than Once

It’s not difficult to make a game that’s enjoyable when you win. The trick is to make a game that’s fun even when you lose. This usually means your game has some great aspects that have nothing to do with the winning conditions. It probably has some great elements, such as meaningful choices, great social interactions, or an immersive theme.

The desire for your playtesters to keep playing usually also means your game is well-balanced. In other words, the players genuinely believe the winner played the game well and earned their victory. While luck does play a role in many games, a fair game is not determined by luck alone. A balanced game allows players to take risks and maximize their gains when a lucky opportunity presents itself.

Having players want to keep playing your game attests to the game’s replayability. The phrase “Leave them wanting more,” is well known in show business. I believe it also applies to game design. You want your game to be just shy of 100% satisfying. You want to tease your players with the idea there is more to your game than can be experienced in one session.

4. When Playtests Yield Only a Trickle of Critical Feedback

Initial playtests typically produce a flood of feedback. Most games are a delicate balance between player and design elements. Player elements let players know what components do. Design elements dictate how components interact with each other. The initial version of your game will likely have these elements drastically out of balance. Even the most novice of playtesters will be able to see where these elements fall short to produce a satisfying game experience. Consequently, your first playtests will often generate a deluge of feedback about what elements to add, eliminate, or change. However, with each iteration of your game, elements will begin hitting the right notes. Overall, you’ll receive less and less feedback on your game as you iterate the design.

As you near a game design that works well mechanically, you’ll likely only receive a trickle of feedback from playtesters. It’s possible playtesters won’t find anything to critique. But no game is absolutely perfect, so you should receive some feedback no matter how far you are into development. Furthermore, the critiques will often be repeated suggestions from past playtests. If you’ve already reviewed those past suggestions and decided those changes are not in line with your design vision, then you’re likely nearing the end of game mechanic playtesting.

It’s possible during these late stages, a playtester will give you feedback you’ve never heard before. That has happened to me and it is harrowing to think there may be major flaws you and your playtesters missed. However, if you’ve gone through several playtests with no new critiques, then whatever flaws you have in your game design are likely extremely minor.

5. When Your Trusted Network of Game Designer Friends Says You’re Done

I’ve mentioned it before in my article “Jumpstarting Your First Game Design” but it’s worth saying again—your most valuable resource as a designer is a trusted network of game designer friends. You want a network who will be 100% honest with you even when they are critiques you don’t want to hear. Game creation requires time, effort, and passion. It’s difficult to remain objective about a project that you’ve invested so much into. Your trusted network will help you see things that you can’t.

One advantage of consulting your trusted game designer network is they’ve watched your game evolve from concept to working prototype. They’re familiar with your game design goals. They’ve seen the problems you uncovered and how you solved them. They’ve seen which solutions have worked and which haven’t. They can offer a much more comprehensive evaluation of your game than any one-time playtester.

If possible, take full advantage of your trusted game designer network and talk about your game in-depth. I recommend playing your game once then having an intensive feedback session. Review your design goals. Talk about how you think it meets or surpasses your goals. No game is perfect, so share what concerns you have about your game. Ask them if you should take some time to try to resolve those issues or if they are relatively minor and you should move forward with your game design.

6. When Gameplay Highlights What is Fun and Unique About Your Game

As you’re playtesting, you will likely find some aspect of your game that players tend to notice more than other aspects of your game. Maybe you’re using a game component in a new and interesting way. Perhaps your game allows players to interact with their friends in a unique and enjoyable manner. The feedback you will often get is something like, “I enjoyed this aspect and I want more of it!” This is likely what makes your game fun and unique, and highlighting that aspect is key to designing a great game.

This aspect may be something you planned or, as is often the case with my design process, a complete surprise. In either case, it’s worth the time to reflect on this aspect and try to think of ways to bring that aspect to the forefront of your game design. In early iterations of game design, you may find this unique aspect buried under less interesting game mechanics or it may take several turns for players to get to that aspect. If that aspect is particularly enjoyable, players may spend their turns just to get to that point of fun. Do your players a favor and find ways they can experience this fun as early as possible and with as little effort as possible, maybe even on the first turn. If you see your job as a game designer as ensuring you quickly and clearly connect the player with the most fun aspects of your game, you’ll never go wrong.

If this fun aspect is a complete surprise, in other words, if this fun aspect was not part of your original game design vision, this would be one of those good reasons to reconsider your game vision. It’s OK to change that game vision if you can honestly see how your original vision and this surprising new fun element complement each other. However, if you honestly can’t reconcile the two, then it’s OK to note that fun element and maybe save it for a future game.

My Best Advice

If you’ve put your game through months of playtests, got feedback from a variety of playtesters, made improvements after each session and feel close to the final game design, you’re on the right path to an amazing game design. Keep in mind, no game is perfect. There will always be minor flaws in your game. But most players will likely never even notice these minor flaws in a well-tested game. Unfortunately, as a game designer you know your game design intimately from its greatest elements to its minor flaws. It’s normal to have doubts about the most elegantly designed games. Moving to the next stage of game design is less about dealing with the minor flaws and more about finding ways to be comfortable with the minor flaws. Establishing your own consistent process to review your game design is key to instilling confidence in your game design and help you to move forward beyond the game mechanic testing stage.

Congratulations for this article. Will help me a lot in my game designs. I am always thinking that what I am doing is not good enough. I believe that I can use this point to be more “scientific” about my design and less “passionate”.

Thanks.