Every game is an “Abstract” game. Let’s get that out of the way early. Every game you will ever find is, to varying degrees, an abstraction of whatever concept it is attempting to convey. Even heavily-themed games like Terraforming Mars or Blood Rage are abstract. No game is a literal representation of its topic. However, some games go out of their way to try and give you a feeling–an experience–that transports you. Games like Captain Sonar or Spyfall, while they can’t put you on a submarine or in an espionage agency, work hard to make their mechanics serve their theme. To me, an abstract strategy game is the exact opposite of that.

The theme, if there is even one present (which is often not the case) is superfluous, thrown on like a blanket and, wherever necessary, made to serve the mechanics of the game instead of the other way around. As publishers grow cannier, they have realized that some semblance of theme can help a well-designed game ascend to a higher plane of popularity. Take, for example, Santorini, which was actually first created in 2004 to little or no recognition. 12 years later it was reprinted, replacing its cubes and blocks with elaborate miniatures and tiny buildings. The rules were largely unchanged, but a more visible theme helped propel its Kickstarter campaign to make over $500,000.

This is what I mean. Nothing fundamentally changed about Santorini from 2004 to 2016. The theme served the mechanics, it just got a new lick of paint. So, by my definition, Santorini is still an abstract strategy game despite the tiny Grecian miniatures and their blue-domed domiciles. Not every game on this list even makes the attempt at theme, as the prototypical hallmark of abstract strategy is a lack of representational pieces or narrative, but the newer games attempt to varying levels to give your game a raison d’être.

It’s also worth noting that abstract games are not for everyone. Their emphasis is often solely on strategy and skill, leaving out elements that make games more social or experiential. In my experience, gamers who play in large groups tend to dislike abstract strategy which, for reasons I’ll cover in a moment, tend towards a 2-player limit. Abstract strategy games don’t lead to conversations and laughter, but more often to solemn silence and furrowed brows. So your love for this style of game hinges entirely on your love of pure, balanced competition.

I like the social side of gaming as much as the next person, but the root of my love for gaming comes from my competitive nature. I learned my first board games almost entirely because I wanted to beat my older brother at something, and in my teenage years I fell deep into the well that is tournament Magic the Gathering. For me, the draw of a good abstract game is twofold. First, it allows you a kind of mastery that you can never dream of in another game, simply because the ruleset is so concise. Whereas it can take weeks just to learn a game like Caverna, a good abstract can be taught in minutes and lets you get right down to the core of wrapping your head around the strategy of it.

Second, and the reason I like the 2-player maximum of most abstract strategy classics, is the elimination of chance. Chance is a nice spice for games to have, giving a variability that can elongate a game’s lifespan by making each replay different. Conversely, though, a game that has zero chance becomes a pure exercise in your skill against your opponent’s. Each game will still be different, but not because of a random roll of the dice or draw of the deck; each game will be different because you are different, your opponent is different, and as you change as players the game will change with you. In a game like this, every loss becomes an opportunity. Far from being able to chalk up your defeat to the confluence of bad luck and multiple enemies ganging up on you, losing an abstract game is usually because your opponent is just better than you. For some people, that’s infuriating. For others, it’s exhilarating… (check our our top 6 two player games list for more in this genre).

“Playing to win involves viewing a loss as an opportunity to learn and improve.”

–David Sirlin, Playing to Win: Becoming the Champion

Hive (John Yianna, designer)

Hive makes this list through one key virtue: its portability. While in truth this delightfully-tactile game of chunky, hexagonal bugs is a lot like chess without the burden of history, the best thing about Hive is that there is no game board. You can play on any flat surface, placing pieces adjacent to each other to create the titular “Hive” as you attempt to surround your opponent’s queen bee. Each bug moves differently, much like in chess, and the learning curve to this one is slightly steeper than most of the games that will follow on this list. That incline is what keeps this one so low on the list.

Contrary to what I talked about earlier, this is an abstract that will take people a little while to grasp the rules, keeping them at bay from their wholehearted enjoyment of the strategy that much longer. That said, if you are able to find a player as enthusiastic about this game as you are, then this has the potential to rise much higher on your own personal list.

(Read our review of Hive).

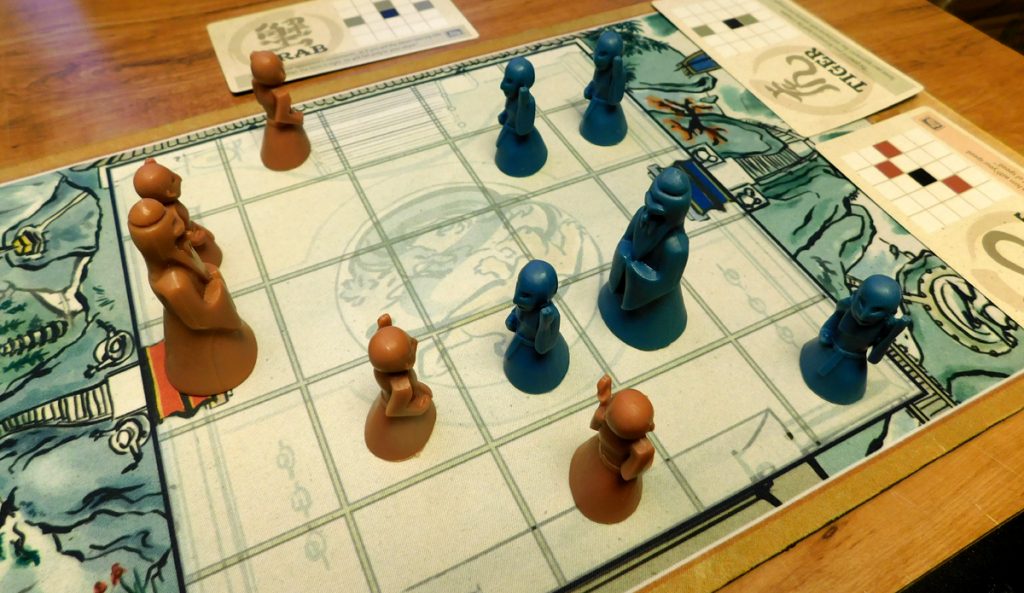

Onitama (Shimpei Sato, designer)

This is a marvelous little game that seemingly does the impossible: it provides you with a wealth of possibilities while remaining pure and unimpaired by chance. A tactical movement game in which your army of 5 is going up against the other player’s on a compressed 5×5 field, Onitama doesn’t assign its movements based on piece type, but rather uses a deck of cards to determine what martial arts “moves” these pieces know. Only 5 will be used per game: each player starts with 2 and 1 is placed to the side of the board.

Here’s where things get good: You can execute either of the moves you possess on your turn, but you must then immediately swap that move with the one that’s sitting off to the side. So Onitama never becomes rote, with different combinations of moves each time you play, but perfect parity as those moves cycle from player-to-player throughout the match. Now, these moves are often fairly limited in scope, and Onitama can, at times, feel like running in mud, but that feeling goes away when you embrace the impact that even the smallest move can have on the game down the line.

TZAAR (Kris Burm, designer)

The GIPF Project is kind of the magnum opus of abstract strategy games. A series of 8 games (GIPF, PUNCT, DVONN, YINSH, TZAAR, ZERTZ, TAMSK, and LYNGK) all designed by Kris Burm, each game in this series was an exploration of the abstract, a look at a different facet of strategy in a world devoid of any kind of theme or setting. Even the names are gibberish, random strings of letters selected by Mr. Burm to give the impression of being words but, really, signifying nothing.

Every game in this series is unique and meritorious in its own right (ZERTZ narrowly missed being included in this list, itself) but TZAAR is undoubtedly the best. It’s the easiest to teach of the games while retaining all the strategic complexity of the others. Played on a hexagonal grid with a gap in the center, each player starts with a collection of pieces on the board. There are three different types of pieces, and both players have the same distribution. Gameplay involves either moving your pieces in straight lines to eliminate opposing pieces or stacking your pieces on your own to make them more difficult to remove (you can only eliminate an opposing stack with one of equal or greater height). As soon as one of your three types of pieces is no longer represented on the board (or you can’t make a move) you lose.

This seems simple enough until you start to realize the delicate interplay between fortifying your pieces to protect them and actually inflicting damage on yourself by covering up valuable pieces (effectively eliminating them from play) via the fortification process. Like the best games, TZAAR is a puzzle and one that you’ll find yourself wanting to play again the moment it’s finished. And really, what more can you ask from a game?

Pente (Gary Gabrel and Tom Braunlich)

Pente was inspired by the grandfather of all abstract strategy games: Go. The similarities are evident both in the large grid of a board and the simple glass tokens each player controls. Like Go, Pente is a game of area of control, but unlike Go it has been made to be streamlined and cutthroat.

Designed in 1977 by a dishwasher at a pizza joint (Gary Gabrel), it was made to be a pastime for customers to play while waiting for their deep dish. As such, the core of Go had to be distilled, as it is a game that can routinely take hours or more to play. So Pente boiled things down their essence. Instead of fighting for large swaths of land, you were now fighting for rows of five or two. Create a row of five in your color, and you win. Bookend exactly two of your opponent’s pieces in a row and you capture them. Capture 10 of their pieces and you win.

The dual paths to victory means you can never steer too fully towards one or the other, because doing so leaves you vulnerable on the other front. And because you can only capture rows of 2 (never more and never less) there’s an incentive to play offensively when you can, because if you let the moment pass it won’t come around again.

The mass-produced version of Pente was first published in 1977 and has been in-and-out of print since. I started playing with a garage sale copy in 1995 and have continued to play it through the intervening 23 years. Considering the golden age of board games that we live in, any game that can hold my attention for over two decades is one worthy of a place in the pantheon of greatness.

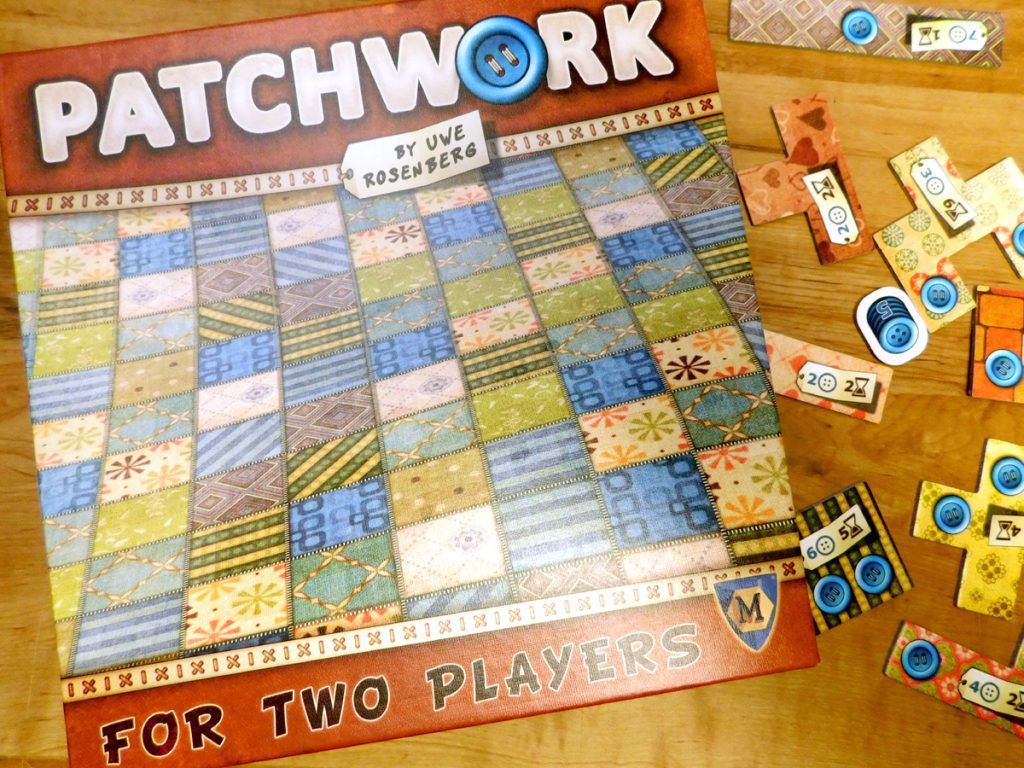

Patchwork (Uwe Rosenberg, designer)

At a glance, Patchwork is the most thematic of any game on this list and one that some might claim isn’t truly an abstract. But little in the game has anything to do with sewing a quilt, and it can only be considered a “theme” in the loosest of terms. Moreover, that “theme” bends and contorts to fit the game, not vice versa, which makes it an abstract game to me. And what an abstract game it is.

Best known for his increasingly-heavy games (Caverna, Agricola, A Feast For Odin), Uwe Rosenberg’s simplest game is perhaps his greatest masterpiece. In Patchwork, players work to place polyominoes (Tetris-esque pieces) in the most efficient way possible, as every uncovered space on their playerboard will count against them at the end of the game.

Patchwork has two incredible systems that work in perfect unison. The first is its dual currency system. Each piece you take needs to be accounted for in two ways: movement and buttons. Pieces cost buttons, but every piece will also move your pawn forward a certain number of spaces, and when you run out of spaces the game is over for you. This makes every decision agony, because sometimes the biggest pieces shoot you forward like a rocket, eroding your runway and also leaving the door open for your opponent to destroy you before you even get to play again (the other player will keep taking pieces until their pawn passes yours).

On top of this is the selection field. At the start of the game every single piece is spread in a circle and a marker is placed randomly between two pieces. On your turn, you have the option of claiming any of the next three pieces from wherever that marker sits. On the surface, this is simple enough. Three choices. No big deal. But as you peel back the layers you begin to realize that, with this simple setup, Rosenberg has laid the burden of knowledge squarely on your shoulders. From the very start you can see the game in its entirety and have the option to plan ahead to the very end. Now, your opponent will no doubt derail those plans, but that doesn’t make the planning any less satisfying.

Patchwork is often dismissed as simple, or a kids’ game, because of its apparent simplicity, but calling it simple is, in itself, a simplification. Patchwork is every bit as rich as Rosenberg’s more complex fare, but you will only get out of it what you put in. Go in with an open mind, ready to run with the options it gives you, and you will never look back.

Quarto (Blaise Muller, designer)

A riff on the “four-in-a-row” genre, Quarto is made up of 16 pieces, all of which are a mix of tall/short, light/dark, hollow/solid, and round/square. To win the game, you simply have to place a piece somewhere on the compact 4×4 board that makes a row of 4 with at least one of those traits in common. That, alone, makes Quarto interesting, but what makes it my favorite abstract strategy game of all time is its twist: your opponent chooses what piece you get to play on your turn and you choose theirs. It’s this seemingly-simple spin that makes this game (which can never extend beyond 16 turns) so knotted and complex.

While your choices have a very low ceiling, you find yourself staring at those pieces as if there are twice as many, because you know that, if you lose, it will be with a piece that you gave your opponent. While the spatial reasoning and pattern recognition required for Quarto make it great, the skill that it tests more than anything is your attention. The small playing field makes it seem deceptively-straightforward, and as such it’s easy to be lulled into a lackadaisical approach. But make no mistake, if you lose focus for even a moment that’s all it takes for a single path of traits to slip past your radar and allow your opponent to win.

Quarto is like a fencing match: it’s quick, it’s breathless, and it will keep you on your toes. Consistently in print for 27 years now, Quarto is not only the quintessential abstract strategy game for your collection, but also an excellent way to introduce new players to what abstract games are all about.

(For your consideration, here are the games that didn’t quite make the cut but are well worth exploring: Kuzushi, Dragon Face, Abalone, Zertz, Push Fight, Kamisado, Azul, Kulami, Twixt, and Eternas)

There is a photo at yhe top of this article depicting a game i don’t see in the article.

Square tiles on round coasters, a multi grid board in the background: what game is in this photo.

Please and thank you!

Deborah, the game in that photo is Azul. Check out our review:

https://www.meeplemountain.com/reviews/azul-review-tile-your-way-to-victory/

While I don’t know if the designers of Pente knew about them, the game is actually more a derivative of Go-Moku and Renju (Both variations of the same game, the latter being more balanced between the first and second players). Both of those games are played on Go boards with Go pieces and the object of the game is to get five of your pieces lined up in a row.

I am missing Japanese chess shogi 🙂

Better than normal chess and one of the best abstract games for sure.

Rock Paper Switch by Mindware is a good new one.

It’s Rock Paper Scissors turned into a chess-like board game.

[Editor’s note: Robert is the designer of this game]

Logan,

Thanks for the excellent article on abstract games. Trxilt is a game that you should check out. It was inspired by the Dots and Boxes game. Game rules: https://trxiltgames.wixsite.com/trxilt-game

Have a great day!