Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

Quo Vadis? is an early entry in the storied catalogue of Reiner Knizia. Set in the Roman Senate, players negotiate with one another to advance members of their individual factions from room to room, ultimately trying to reach the main Senate chamber. The title is strange. It’s Latin for “Where are you going?,” and is likely a hard-to-parse reference to the Bible.

Quo Vadis? is a minor classic, a cult affair. In my experience, it is not the sort of title people speak of with hushed reverence so much as a warm fondness. Even its fans would not argue, I don’t think, that the game is an out-and-out masterpiece. Nonetheless, it has its admirers. First published in 1992, and entirely out of print since 2005, the game hasn’t had much opportunity for reappraisal.

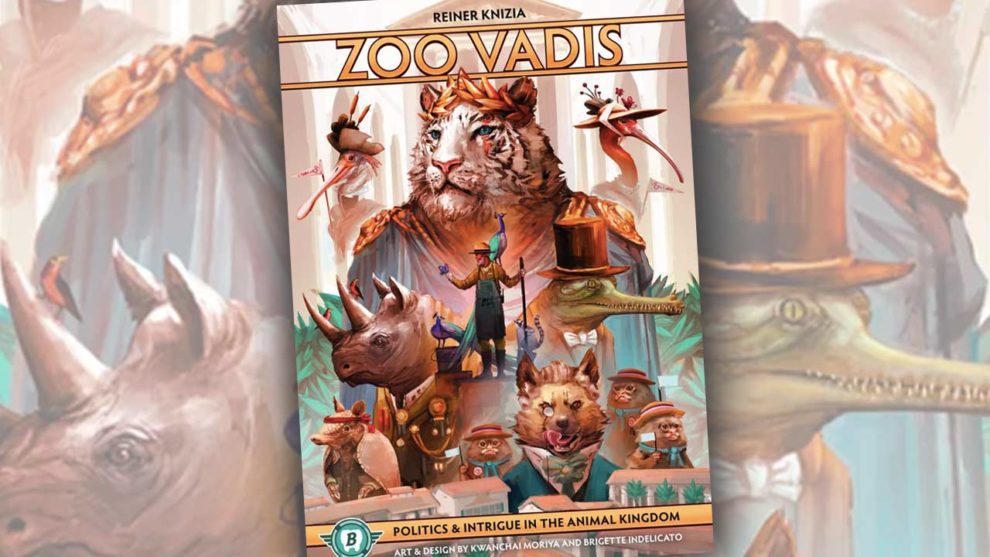

Arizona-based publisher Bitewing Games is doing something about that, bringing Quo Vadis? back in a beautiful new edition under the title Zoo Vadis. This is not a straight reprint. Bitewing and Knizia have worked together to shake up the status Quo. They’re dropping the question mark and adding zoo animals. If Quo Vadis? asks “Where are you going?,” Zoo Vadis calmly tells you, “You are going to the zoo.”

The Rules of the Game

It’s election season in the zoo, and various factions of animals are vying for power. The Armadillos, Crocodiles, Hyenas, Ibises, Marmosets, Rhinoceroses, and White Tigers all want your vote, and they are willing to do just about anything—read: one of four things each turn—to get it.

Zoo Vadis is charming on the table, maintaining Bitewing’s early but promising Hall of Fame batting average. The drab setting and aesthetics of the original—look, I like it too, but other people aren’t like us—have been replaced with a colorful map and tall wooden tokens. Players now have privacy screens bearing striking anthropomorphized illustrations by Kwanchai Moriya. The little Marmosets, with their little flags clutched in their little fists, look adorable. The White Tigers look suitably imperious. The Rhinoceroses look fascistic. The Armadillos look like they have some thoughts about the kinds of flowers being planted on Main Street.

The rules are straightforward enough. On your turn, you can:

- Place a piece in one of the four entry enclosures. This requires, of course, that there is space.

- Advance one of your pieces from one enclosure to another. This requires a sufficient number of votes from pieces in the enclosure of origin. When you advance, you collect any victory point token that may be on the path between your point of origin and your destination.

- Advance a Peacock from one enclosure to another. The Peacocks are not running for office, and therefore do not require consent to advance.

- Move the Zoo Keeper. The Zoo Keeper, Caesar in the original game, allows for free advancement along the path he stands on. On your next turn, provided the Zoo Keeper is still there, you won’t need anyone else to approve your advancement. The tradeoff is that the Zoo Keeper covers the point token on that path, so you won’t get to collect it.

Advancing, and the negotiations around it, form the bulk of the game. To advance from a Zoo Keeper-free enclosure, you need a majority of the votes. A plurality will not suffice. The threshold for majority is determined by the number of spaces in the given enclosure, occupied or not. A lone, solitary piece in a three-space enclosure cannot advance.

Let’s say the Ibis has one piece in an otherwise empty three-space enclosure. The Crocodile moves in, and so does the White Tiger. Now, if the Ibis wants to advance, they will need to either move the Zoo Keeper and hope he’s still there when the round gets back to them, or grease the palms of another player. You can offer anything within the scope of the game. Victory points from your stash, the promise of a vote later down the line, the promise not to vote for someone else, the promise to place or not place, advance or not advance, to move the Zoo Keeper, etc.

In the fine tradition of negotiation games, these promises need not be honored later. The only rule regarding following through on a deal is that anything which can be resolved within the scope of that single turn must be resolved. That is to say, I can’t promise to give you points for a vote, move my piece, and then stick my tongue out at you.

This, I feel, is a wise rule.

The game ends once the top enclosure is full. The player with the most victory points is the winner, though there is one catch. If your pieces aren’t represented among those at the top of the board, you are ineligible to win.

Everything Old Is Zoo Again

Save for some thematics, what I’ve just described is Quo Vadis? to a…well, to a “Q.” There are, for those who were already familiar with the game, some differences. Zoo Vadis introduces neutral pieces, Peacocks, which I like very much, and asymmetrical faction powers, which my play groups ended up preferring not to use.

Peacocks are set out according to player count. They strut about the zoo, mostly minding their own business, but they can be persuaded to throw their support behind a candidate for a 2-point chip. In a three-space enclosure with a Peacock, a Crocodile, and a Marmoset, the Marmoset can leverage paying 2 points to the Peacock to deflate how much it will cost them to get support from the Crocodile.

Peacocks can advance, the same as any other piece, though they never require consent. They can be moved defensively or offensively, depending on the game state. I could move a Peacock in to make it cheaper to advance on my next turn, or I could move a Peacock in to keep somebody else out. They bring a pleasant background hum of extra tension to the design, keeping the space alive for lower numbers of players. An A+ addition.

The faction powers introduce further fodder for negotiation. Each animal has an ability that can be sold to other players. Crucially, you cannot use your own ability on your own pieces. The Hyenas allow another player to move the Zoo Keeper before or after their action on the same turn, for example. The Armadillos give access to secret tunnels which do not require majority support to utilize. The Ibis lets you move into an already full enclosure.

In keeping with Knizia’s general ethos, none of these abilities are particularly complicated. At higher player counts, though, trying to remember what everyone else can do for you gums up the works. Everyone gets a little too lost in the rules.

I’ll put it this way: A game of Zoo Vadis without the player powers, even at six or seven players, goes by in a breezy 30-45 minutes. That’s the case even if everyone at the table is new. A game of Zoo Vadis with the player powers, even at four or five players, can creep up above the hour mark. At that length, you feel the design start to buckle.

Where Goest Thou?

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: I get more joy out of playing most fair-to-middling Knizia designs than I do out of playing most consensus great modern games. Zoo Vadis is certainly not fair-to-middling, but it is a perfect illustration of why even Knizia’s worst designs will always have at least a momentary home at my table. He has always understood that games are great because of the people at the table. He provides a framework for interaction, rather than an object that’s meant to take up all your bandwidth. A game of Zoo Vadis is spent looking in the eyes of your fellow players, not staring at the board.

Do I have complaints? I do. I already talked about the player powers, but if they don’t work for you, they are easy to omit. The rulebook even tells you how to adjust play if that’s the case. I’m also not entirely sold on the arc. The end always comes about in a way that isn’t entirely satisfying, and the accrual of points feels transparent enough that the winner has never been a surprise. These are the barriers to loving it, but I mean loving it. Without those issues, we’re talking about an all-timer.

Zoo Vadis has moments of transcendence. A player moves a piece up an enclosure and the whole table feels that turn as pregnant with the promise of what that player intends to do next. That is pure magic. Quo vadis? Where are you going? No idea. Quo vado, though? Ludere vado. I am going to play.