Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

With so many games on the shelf, deciding what to play can be a process all its own. One of the thrills of writing reviews is that every now and then I get to suggest a game that makes everyone cock their heads to the side and raise an eyebrow.

“Ladies and gentlemen, I give you Zestrea, the game of Romanian arranged marriages.”

Thankfully, there is a story to accompany this particular game that helps close the deal. During a Kickstarter campaign for their graphic novel The Lost Sunday, I had the chance to correspond briefly with one of the author/illustrators, Maria Surducan. It’s a beautifully illustrated story that combines a Grimm tale with a traditional Romanian fairy story. Not long after, this fascinating little game came across the wire for review. What a delightful surprise, then, when I saw the same Maria Surducan as the illustrator of Zestrea! I love when crissing paths later cross.

Zestrea is a social game for three to six players in which players take up the role of Boyars—aristocrats of a bygone generation responsible for the welfare of the people of their village. In the past, we’ve seen games that feature marriage as a key element as well as games that brush with parenting. This 2019 release from Pronoia keeps matrimony in the hot seat from start to finish. Through a lengthy series of hard times, Boyars attempt to raise children and intermarry with the surrounding villages in order to secure a prosperous future for all—but a slightly more prosperous future for their own. Along the way, they must battle hunger and the cruel, and occasionally hilarious, hand of Fate.

“Zestre” is a Romanian term akin to dowry—the payment that often changed hands when a young bride was sent to join her husband in wedlock. Coming out on top in this negotiation game involves preparing your people to endure the hard times while maximizing your zestre. Do you have what it takes?

Matchmaker, Matchmaker…

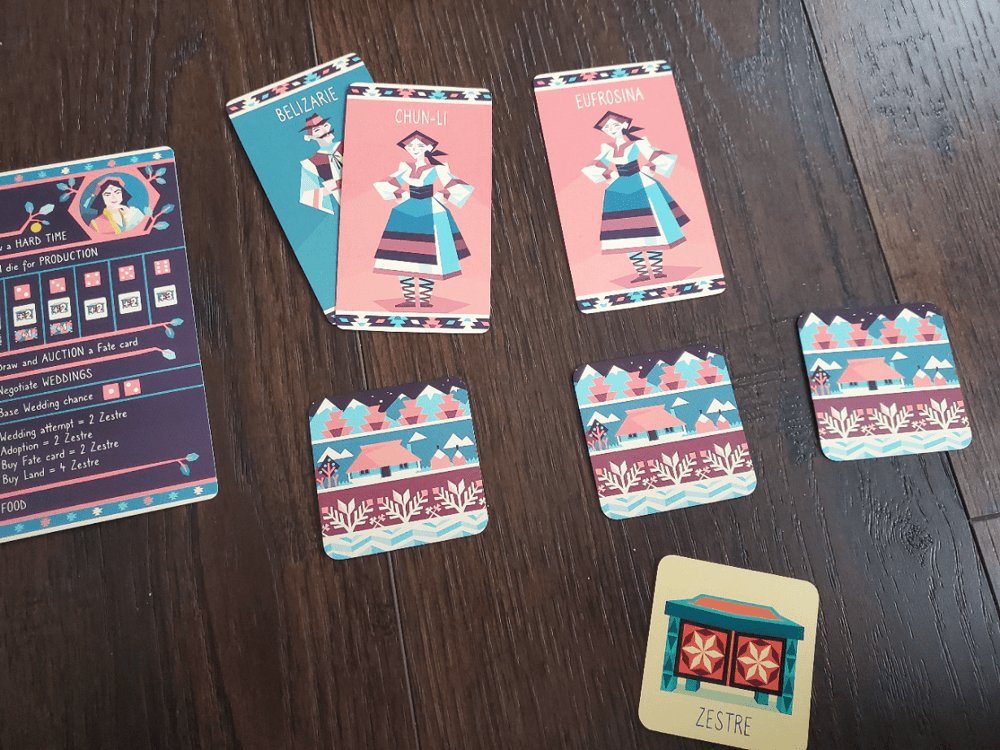

The game’s materials are streamlined. Square cards represent land on one side and zestre—currency—on the other. Villager cards show individually named lads and lasses, hoping to find a marital match. Fate cards offer specific modifiers to villagers and situations. Three Good Times cards sit atop a shuffled set of five Hard Times cards, setting the stage for plenty of drama.

At the outset, each player receives a married couple and three plots of land in order to launch their community. They also receive a Boyar identity card that serves as a guide to the five phases that occur in each round.

Players first share the top card from the Good/Hard Times stack, which introduces a universal scenario. Early Times are all good. Folks are stockpiling zestre and the potential blessings of Fate while marrying with greater ease. After a few turns, though, the Hard Times arrive and the scenarios bring storms, floods, and even government upheavals to shake and shuffle the land and people.

Phase two sees players roll a die to determine the production of the village. The land bears fruit, increasing the flow of zestre into the game. The people likewise bear fruit as babies are born, introducing more mouths to feed and futures to negotiate.

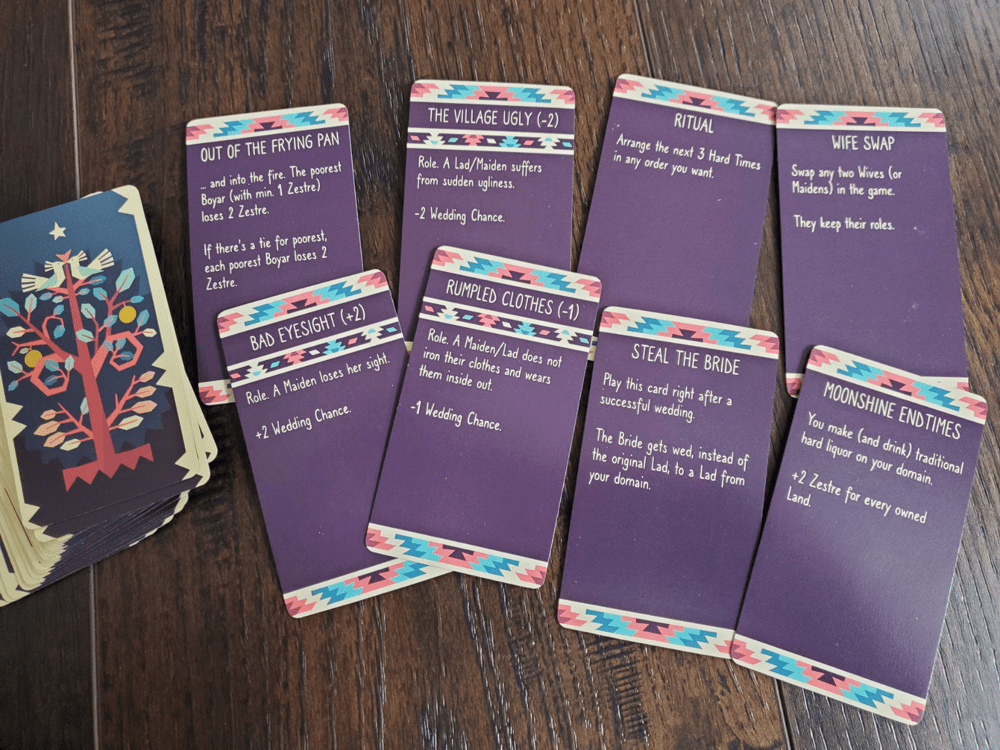

Third, a Fate card is presented to the group for an auction. These cards can then be played into any situation during the negotiation phase. This might mean enlisting one of the young lads to be the village preacher who receives zestre for his assistance any time someone passes away. This could also mean giving poor eyesight to one of the lasses in another village so that she is less particular about choosing a mate. Fate is not always friendly.

The heart of Zestrea is the fourth stage—marriage negotiation—where the barn doors of possibility swing wide open. In a flurry of simultaneous action, players may spend their zestre with reckless abandon, purchasing additional Fate cards, buying land, and adopting teenage villagers. The bread and butter, though, is in brokering wedded bliss. In a scene that sounds and looks like the classic game Pit or the more modern Chinatown, players may trade anything and everything—zestre, future favors, car keys, loaning out the Roomba for a week—in the name of getting these kids together, there are no limits.

But marriage is not a guarantee. When two players arrange to attempt a marriage, the sneaky hand of Fate is still at play in the roll of a die. Rolls of one or two allow the marriage, while the remaining pips deny the union and send the young people home, undoubtedly to fill the melodramatic pages of a tear-soaked diary with angsty poetry. To make matters worse, every attempt at marriage costs two zestre which someone must pay to the state. This is all part of the negotiation.

Those previous Fate cards may also swoop in to help or haunt the marital dreams. Some cards increase the likelihood of marriage by allowing a roll of three or even four to grant the marriage. Other cards hinder by reducing the results that will provide a match. There will be rounds with what feels like a wedding every weekend. There will be others without a single slice of wedding cake. It is nearly impossible to put together a sure thing, which raises the number of emotional outbursts from the Boyars amid the chaos.

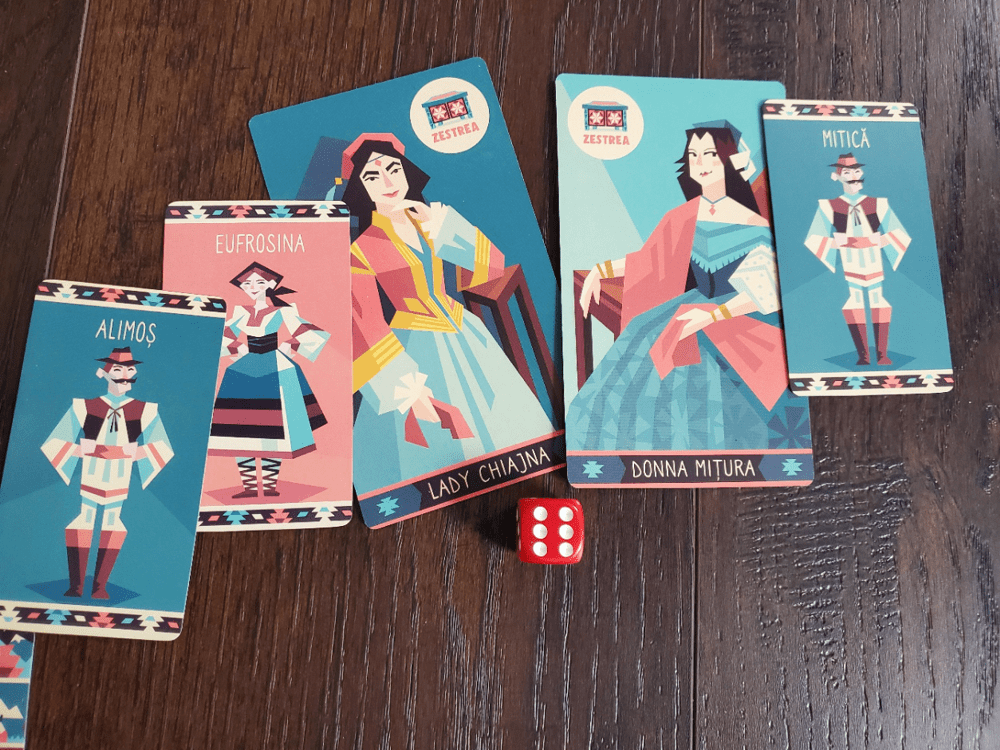

In keeping with tradition, brides leave their village to live with their husband. This equals tension as long as the players have the endgame in view. Every Boyar wants their own village filled with healthy and happy couples, lending immense weight to the negotiations. “I’ll let your Mitică marry my Eufrosina, but when they have a baby girl, you must send her to marry my Alimoş so that our village, too, can grow!”

When the marriage negotiation phase is complete, players must feed their village in the fifth and final phase. Every human unit, whether a single lad or lass or a couple, must have land—a farm—in order to be fed. If there is inadequate land to feed everyone, then zestre must be paid to the state to cover their food. If there is no zestre to be paid, villagers start to die. You heard me. It gets real. Starved family members are buried to the side before the next round commences.

This process continues until the final Hard Time card comes into play. The Boyar with the most married couples in their village receives a bonus of 5 zestre. Players flip every land card, converting it to zestre as well. The player with the most zestre is declared the winner. Ties are decided in favor of the village with the most fed humans.

Playing with matches

My thoughts on Zestrea swing about as wildly as the flailing hand of Fate.

I’ve heard it said that if the first x number of turns in a game are always the same, then those turns should be rolled into the game’s setup. Zestrea could absolutely benefit from this thinking. The first three rounds are always the same three Good Times, and in the same order. Because the production of the land and the people is dice-driven, it is entirely possible that nearly everyone is left out of the first rounds of marriage negotiation. The material blessings—zestre and one Fate card—could just as easily be dealt out or introduced through a teaching round. “In this phase, you would roll to determine whether or not you have any children. Now everyone roll once, and then take either an extra kid or an extra zestre!” This would dole out the necessary resources and prepare the table to dive in.

If the designed setup with the rhythmic Good Times are left intact, the game crawls for three rounds before the flint strikes the steel in the Hard Times. In what is the cardinal sin of a social game, players are sometimes left watching the action for multiple rounds if their lone couple hasn’t started a family to enter the marriage game or they’ve not yet acquired the zestre needed to adopt a contender.

One thing to know about this small box is that it’s meant to be a light-hearted look into the burdens of former times and long-standing traditions. The game does not advocate for a return to 17th century practices by any means. In fact, the game embraces many modern perspectives on marriage as a blend of the generations and leaves its rules open enough to approach the game much differently. The villagers’ names hearken back to an older day and the Fate cards tinker with lives with winsome humor. Laying young Alimoş to rest is supposed to drum up a bit of a laugh, especially when the Preacher’s Boyar sent a pack of wolves—wolves!—through the village in the first place to cause his violent end; and especially when the Preacher then celebrates the extra income from performing the funeral! These are the twisted twists of the design team’s whimsical approach to their own history.

The later rounds of Zestrea are a delight with the potential for hilarious surprises. Once every village has a few singles to mingle, the negotiation round takes on a vibrant life. Players keep their eyes and ears on all negotiations, ready to drop a Fate card into someone else’s conversation to alter the deal. Suddenly Traian was handed the Village Idiot card and he’s not looking much like a viable mate… but look here! Gyuri the village musician is exceptionally ready, and because he’s a musician, his marriage prospects improve on the dice! Whoa ho!

On the one hand, I’ve not had the easiest time getting Zestrea to the table. Something about the theme seems askew to some, or they’re just not into that open and playful style. The younger crowd has had a mixed reaction. Older teens have enjoyed the quirky interplay and the game’s tongue-in-cheek approach to tradition. Younger teens and tweens are unpredictable. We’ve found the family setting to provide an interesting conversational dynamic regardless of enthusiasm.

On the other hand, every time I’ve played Zestrea, there have been moments of cheering and agony, bursts of laughter and disappointment. It is a lively experience, but it requires a buy-in from the group—such is the case with any number of social gaming experiences. Call the villagers by name. Treat them like your own children. Pound the table. Get off your seat and negotiate with a bit of vigor! Invest, and enjoy.

I suppose that is my final word on Zestrea. It’s right for the right people. I don’t like to house rule games to death, or at all really, but if the game sounds like something you would enjoy, I would strongly consider rolling all three of the Good Times into a teaching round for new players to get folks acclimated to the phases and then play six Hard Times cards as the actual game. You won’t regret the madness of the last few rounds, and you will certainly stand for a moment in some heavily antiqued Eastern European shoes. I’ll go ahead and endorse that prospect.

Add Comment