Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

Taken collectively, trick-taking games are a uniquely transparent exercise in variation. Most genres, worker placement for example, have too many moving parts for the variation to be obvious without putting in some effort. I don’t play Russian Railroads and think about Stone Age.

(Yes, yes, I do, but I also write about these things for a…well, you can’t call it a living, but I write about these things for something. You don’t have to live like me.)

Trick-taking games are so evidently variations on a basic concept that new ones can more or less be taught to experienced players by simply saying what’s different from the platonic ideal. “It’s a trick-taking game, but the odds have special powers.” “It’s a trick-taking game where you score points based on how many tricks everyone else has taken.” “It’s a trick-taking game, but you declare the suit of your card when you play it.”

Yokai Septet, designed by Japanese trick-taking madman Muneyuki Yokouchi and published in the U.S. by Ninja Star Games, is a team-based trick-taking game where you and your partner are trying to win 7’s, and the distribution of numbers varies within each of the seven suits. If you’re a seasoned trick-taker, you pretty much already know how to play.

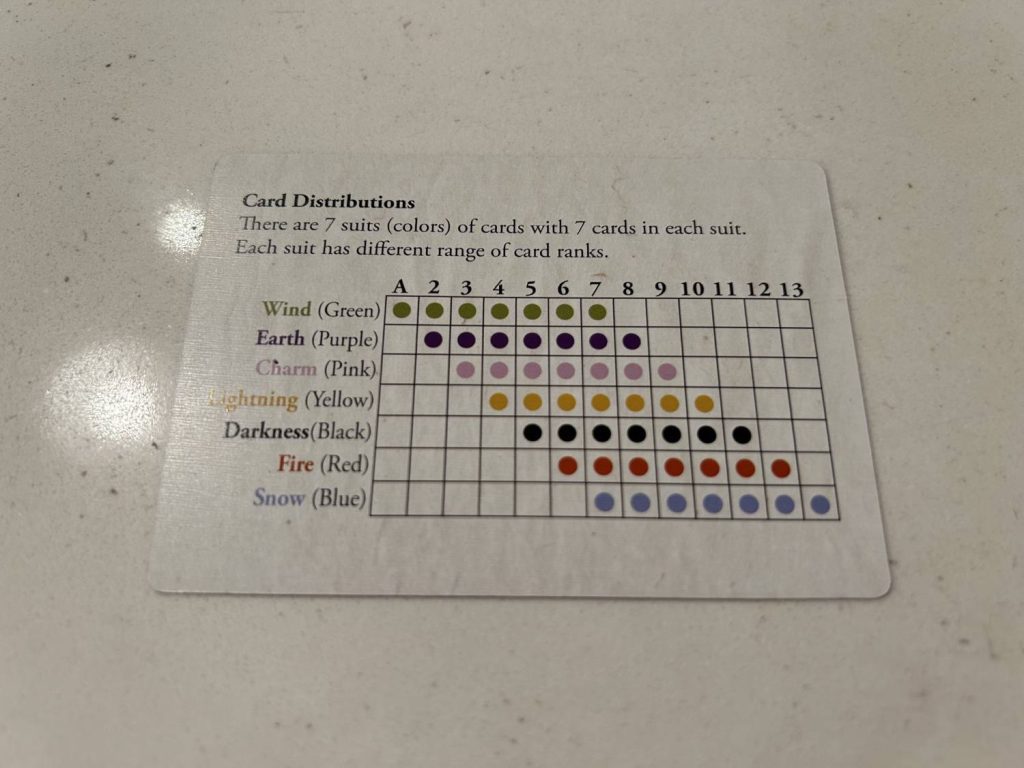

When I say the distribution of numbers varies, what does that mean exactly? Green (Wind) includes cards A-7, purple (Earth) 2-8, and so on until you get to blue (Snow), 7-13. The theoretical impact of this design choice caused me to physically lean forward in my seat as I read the rules. When the aim of the game is to claim tricks with a specific number card, and each suit has a different distribution, you can’t play every suit the same way. You (probably) want to rush the green 7 out as quickly as possible. If you have a few high cards in blue, you can (probably) play fast and loose, safe to assume that you’ll end up with that 7. If you have the pink 9, you’ll (almost certainly) try to hold onto it for as long as you have to.

I like it.

How It Works

The entirety of the deck, save for one card, is dealt out. In a four-player game, everyone ends up with 12. The last card is revealed and determines the trump suit for that round. Players then pass three cards to their partner, a staple of team trick-taking, before the player with the green A leads the first trick.

At that point, play proceeds as you’d expect. High card in the suit wins, unless there’s a trump card. Winner of the trick leads the next trick. You have to follow if you can. Nothing fancy. Any time a player wins one or more 7’s, they set them aside.

A round ends when one of three conditions have been met, in this order of priority:

- One team has won four or more 7s at the end of a trick.

- One team has won seven tricks without winning four or more 7s.

- Nobody has cards left in their hand and neither of the above conditions have been met.

If the first condition is met, that team scores based on the white circles showing on the 7’s in front of them. If the second is met, the team who didn’t win seven tricks scores. The third is an edge case, only possible if the trump card is a 7, but in that instance the team who won the last trick scores.

The first team to seven points is the winner. A four-player game typically ends after two-to-four rounds. A three-player game, which isn’t played with teams, lasts around one-to-three.

Suits Me

Most trick-taking games have three or four suits. Yokai Septet has seven. This impacts the game in two ways, both of which make the game feel less intentional.

In team-based trick-taking games, passing cards to your teammate is often a moment of subtle communication, the only such moment allowed by the rules. Here, the distribution of suits and numbers is such that it’s hard to get anything across. That isn’t necessarily a critique, because it may well be what the designers had in mind. Across my six or seven plays, I’ve come to realize that passing in Yokai Septet emphasizes “I’m giving these cards to you so I know you have them” over “I’m telling you something about what I have.” Rather than a critique, let’s call that an observation.

This is a critique, though: the number of suits makes the game impenetrable. One of my favorite parts of any trick-taking game is before the first trick, staring into the middle distance of your hand while trying to picture the contours of your round. Having seven cards each in seven suits makes that middle distance particularly hard to see. There are too few cards in too many suits. The math is scattershot.

I love trick-taking games because they exist at this particularly fascinating intersection of skill and luck. They’re also intensely social. Everyone is constantly pleased, constantly agitated, constantly bereft, constantly laughing, constantly calculating. That environment is created by the mix of intention and the indignity of the luck of the draw. Yokai Septet doesn’t have quite enough of the former, and it has a little too much of the latter.

Add Comment