Watergate, much like the eponymous hotel, looks utterly innocuous from the outside. Arriving in a smaller-than-expected box, there’s a strong chance that I would have passed it by without giving it a second look if I’d seen it on the shelf of a game shop with its $35 price tag. It doesn’t weigh a lot and the cover artwork is serviceable if not entirely scintillating. However, much like the afore-mentioned hotel at the heart of the scandal, what you find inside of Watergate is fascinating, horrifying, and extremely compelling.

From designer Matthias Cramer, Watergate is an asymmetric 2-player game, casting one player in the role of Richard Nixon as he tries to suppress scandal and survive unimpeached to the end of his term, while the other player takes on the role of the press, trying to uncover evidence and bring forth informants willing to implicate Nixon in his illicit activities. The game plays in a brisk 30-60 minutes and is aimed at players 12 and up. It’s also worth noting that zero knowledge of the history behind the game is required. The events depicted in the game took place roughly 16 years before I was born, so my knowledge of the details was limited to major bullet points and the classic film All the President’s Men, none of which negatively impacted my experience with the game.

Breaking Into Watergate

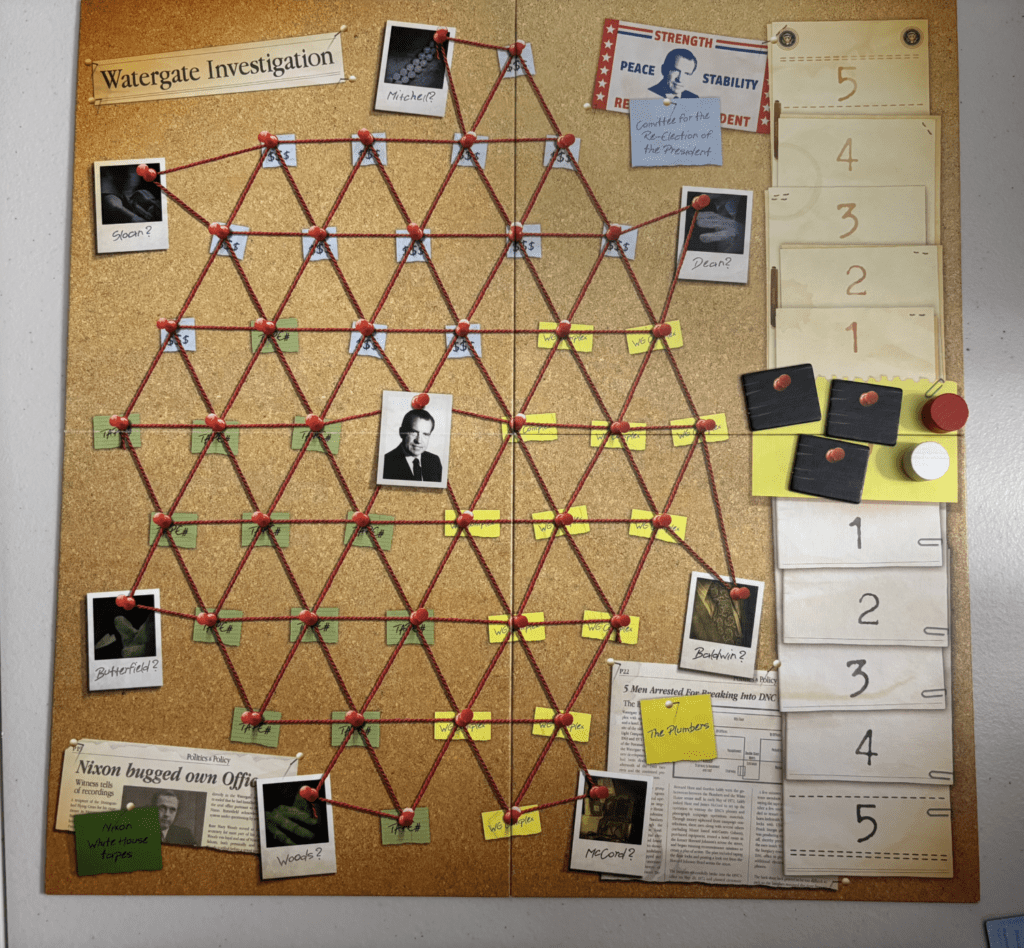

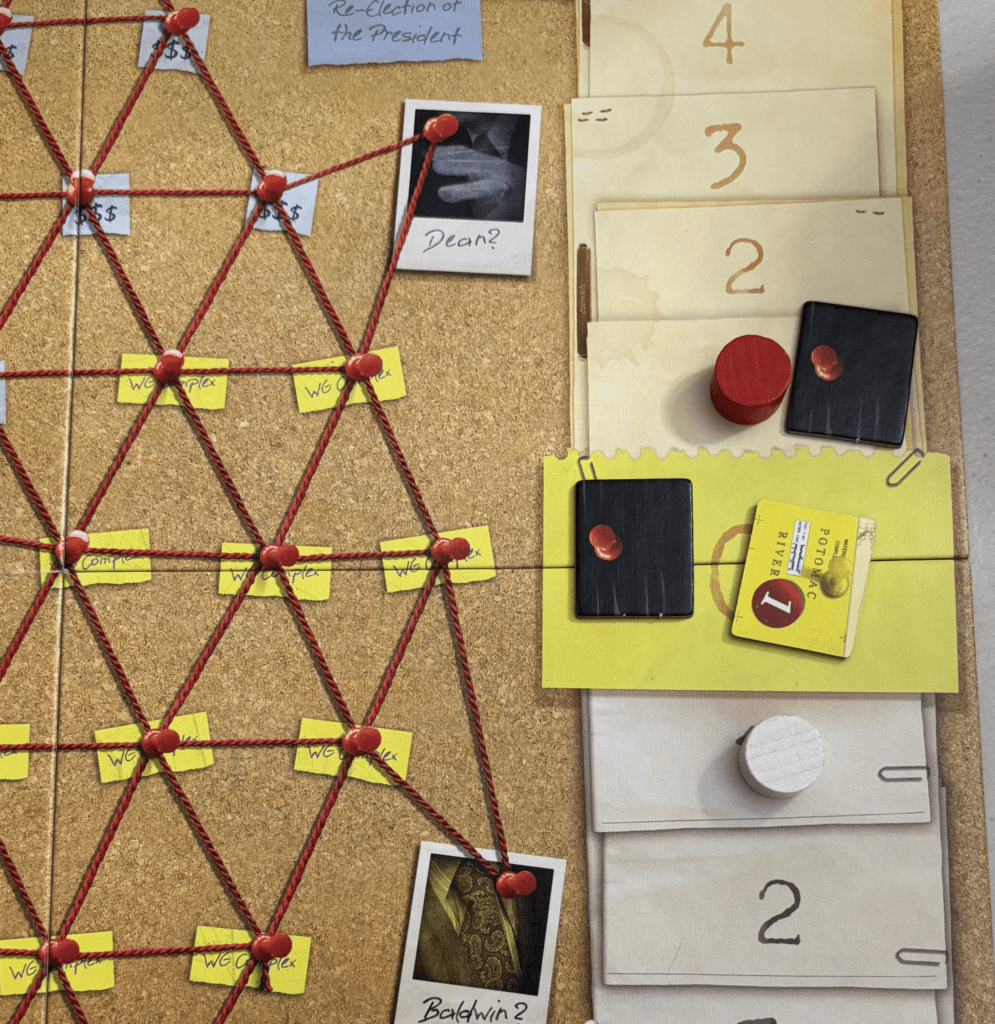

At its core, Watergate is an exceptionally simple game, or rather, it’s two exceptionally simple games. The board is made up of two parts: the evidence web on the left and the evidence track on the right. Each round, the Nixon player will draw 3 evidence tokens blindly from a bag, examine them, and place them face-down at the center of the evidence track along with a white initiative token and a red momentum token. Each of these serves a different purpose, and each is integral in different ways to the two players.

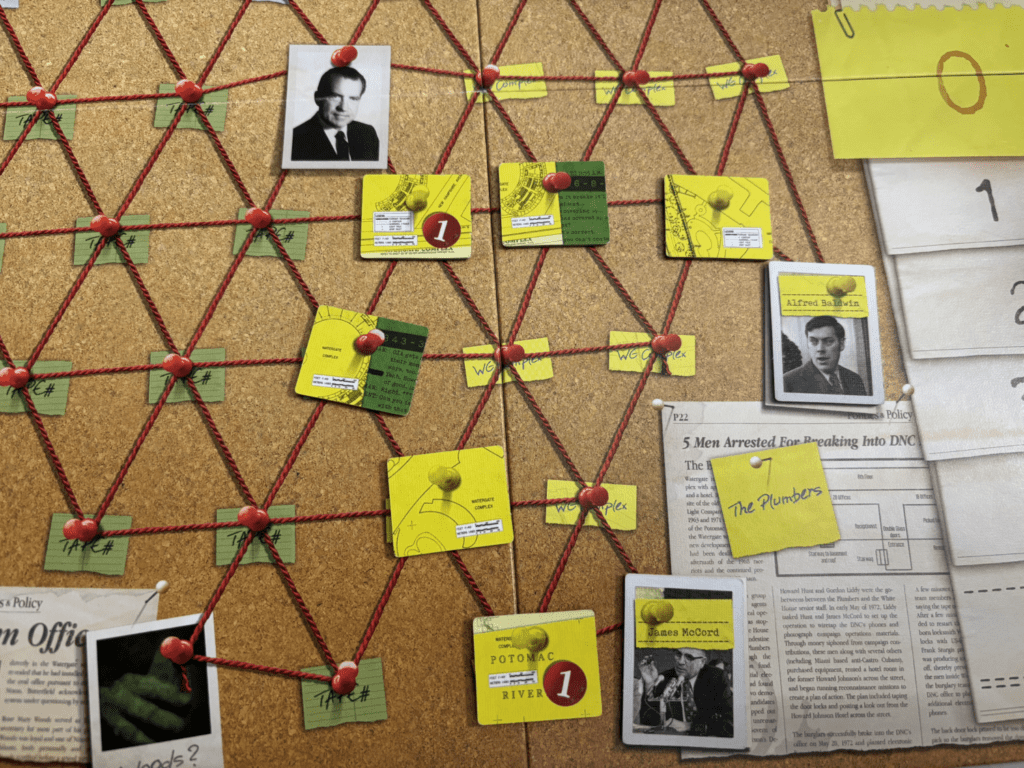

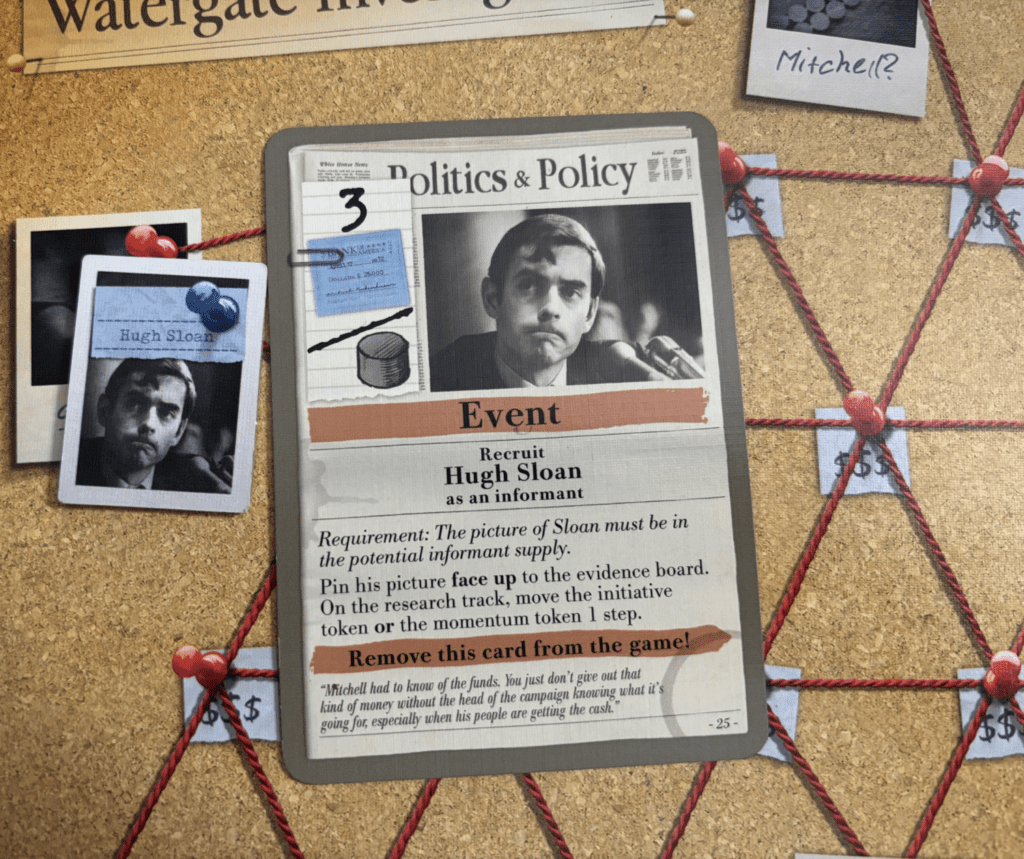

The evidence token colors—green, blue, yellow, or a mix—correspond to the similarly colored areas on the evidence web side of the board. Those tokens, when earned, will be placed on the evidence web, but they can only be placed on spaces that match the colored token. This web is where one of the two major battles of the game takes place. To win, The Press player needs to enlist at least two informants (who also correspond to certain colors and are placed around the edges of the web) and then lay a trail of evidence connecting both informants to Nixon, who’s at the center of the web.

The evidence token colors—green, blue, yellow, or a mix—correspond to the similarly colored areas on the evidence web side of the board. Those tokens, when earned, will be placed on the evidence web, but they can only be placed on spaces that match the colored token. This web is where one of the two major battles of the game takes place. To win, The Press player needs to enlist at least two informants (who also correspond to certain colors and are placed around the edges of the web) and then lay a trail of evidence connecting both informants to Nixon, who’s at the center of the web.

Needless to say, one of Nixon’s goals is to keep this from happening, which he will do by placing any evidence tokens he wins face-down on the web, blocking the paths The Press player is trying to make. For both players, however, the placement of these evidence tokens is secondary to earning them, a battle which plays out at the forefront of the game over on the evidence track.

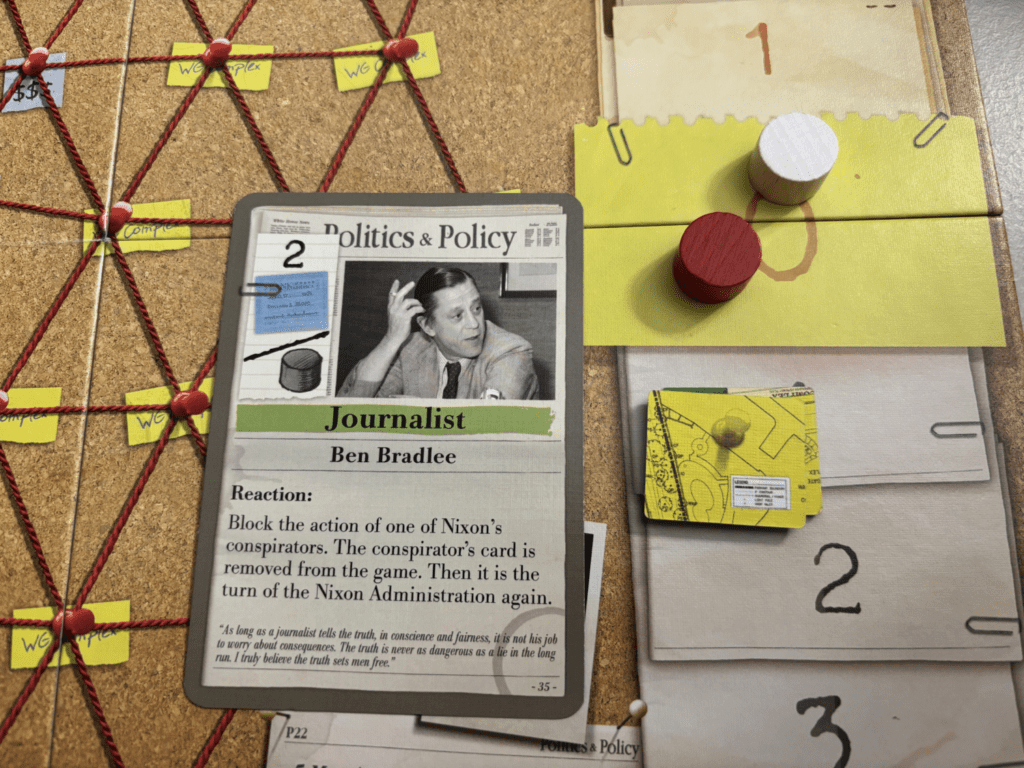

Tug-of-Woodward

The heart of the game is in the cardplay. Each player has their own unique deck they’ll be drawing from each round. Each card has a default numeric value in the upper left corner, which allows players to pull evidence, initiative, or momentum towards them by that number of spaces. At the end of each round, players will gain anything on their side of the track, so all you need to do is get it one space towards you, although keeping it there can be a challenge. Each card also has an ability detailed on the lower half. Similarly to a game like Twilight Struggle, you can either play the care for the value or for the ability. Some cards pull new evidence from the bag, others move multiple tokens at once, etc. Many of the cards are removed from the game when played. The challenge lies in knowing when to burn those one-time use abilities.

And let’s not forget the initiative and momentum tokens. Momentum is the simplest. If Nixon wins 5 of these, he wins the game. He also wins if a new token is needed and none are left in the supply. Momentum tokens can also grant The Press can gain one-time bonuses, but more important to the Press is getting them away from Nixon, keeping his victory at bay. However, the true centerpiece of the game is the white, innocent-looking initiative token.

Burn, Baby, Bern[stein]

Each round, one player will begin with initiative, which means they go first and draw five cards while the other player draws only 4. This may not sound like a lot, but in a game that’s constantly balanced on a knife’s edge, this is the make-or-break point.

The extra card is important, yes, but what’s more important in a game with such razor-thin margins is the ability to dictate how the round ends. Many turns devolve into a back-and-forth fight for a single token or piece of evidence as neither player wants to concede something so vital. When such rounds occur, the difference between winning and losing that fight is often the ability to hold your trump card until last, giving your opponent no opportunity to respond to it. Watergate is a game that constantly feels imbalanced depending who has the initiative at any given time, which to me is a beautiful thing.

How Watergate “Felt” (Get It? Mark Felt? Get It?)

I didn’t finish the very first game of Watergate that I played. I was playing as Nixon (who, admittedly, has a much more straightforward path to victory) while my friend played as The Press. Seemingly every round I would get multiple tokens and bits on my side while his gains evaporated into futility as he became more and more frustrated. The game, he seethed, was imbalanced with a clear advantage allotted to Nixon.

Not wanting the game to be added to the “don’t bring to game day” list so quickly, I gathered up the pieces, spun the board, and suggested we swap roles to see. He agreed and we began our second game, this time with me playing The Press and him playing Nixon. And I continued to win.

The beauty of Watergate, depending on how you look at it, is that neither player will ever feel at ease. Your latest brilliant move is only ever a single card away from being undone and reversed. Although at first glance it seems to have little bearing on how you win, the battle for the initiative token is the key that unlocks your victory, and the sooner both players understand that the sooner those initial feelings of imbalance will be replaced by the perfectly balanced cat-and-mouse duel that makes Watergate not just one of the best games I played last year, but now one of my favorite games of all time.