“Lord of the Rings” is one of the biggest franchises from here to the Misty Mountains, with five significantly sized books, six even more significantly sized movies, an upcoming television series that is sure to be some amount of significance, and multiple generations of influence in the world of “high fantasy”. When I heard there was a board game described as “Tolkien-in-a-box,” I knew it had some pretty big hobbit-sized shoes to fill. (If hobbits wore shoes, that is.) Does War of the Ring soar like the Great Eagles and capture the epic struggle between good and evil? Does it crash and burn in the fires of Mount Doom? Or does it land somewhere in the middle-earth? Read on for our review of War of the Ring, 2nd Edition.

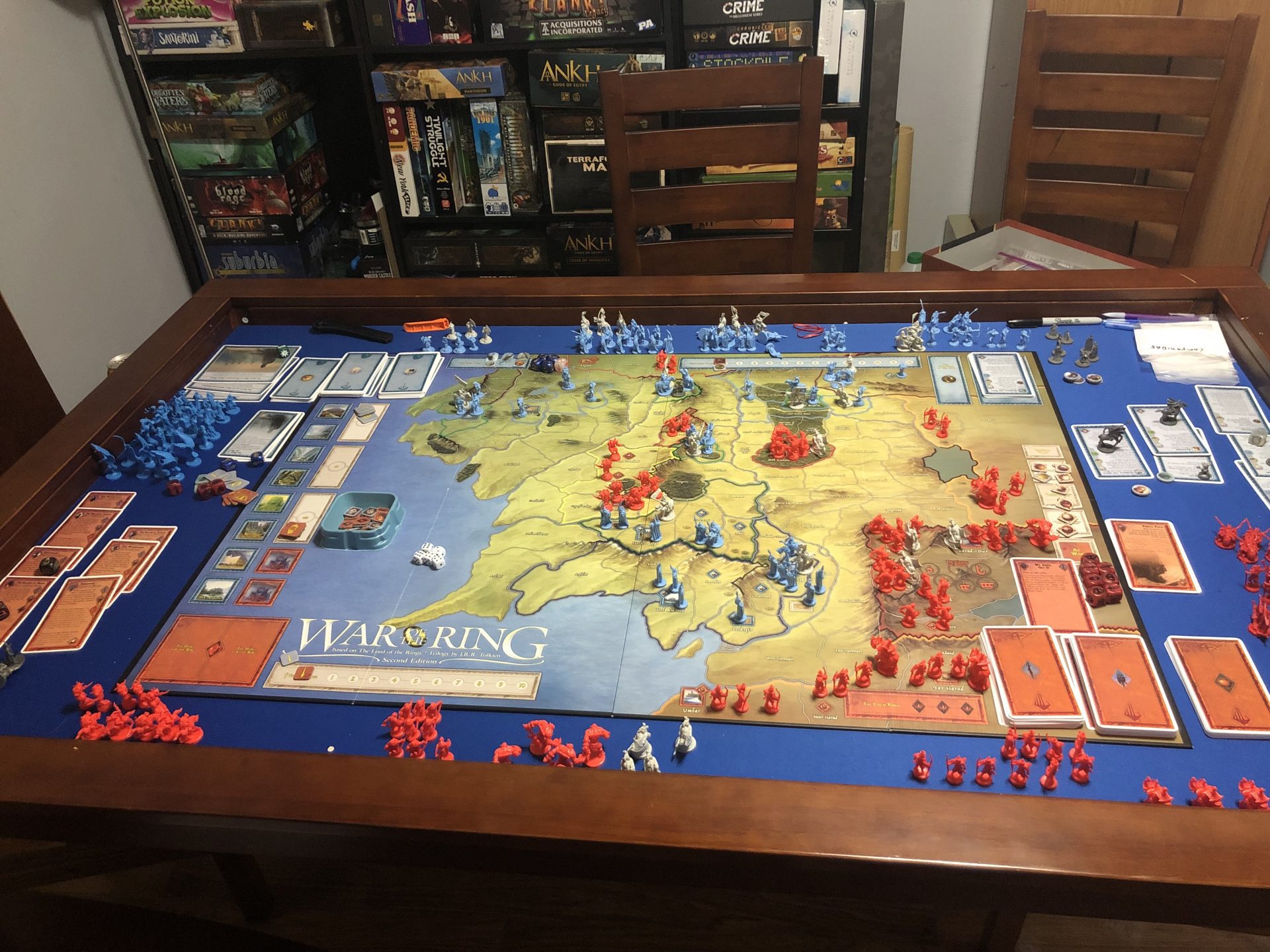

War of the Ring is a game of area control, “troops on a map,” dice combat, hidden movement, hand management, and timely card play. If that sounds like a lot to you, that’s because well, it is. This game is massive, not only in its scope but its size. I have a decent sized game table and it consumed most of it. Like any self-respecting grandiose game it has loads of plastic miniatures to shuffle around, as well as custom sculpts for major characters like Frodo, Legolas, Gimli, and all the other made-up words that call themselves names.

As Meeple Mountain’s primary proponent of the grandiose gaming experience, “epic” is not a word that I throw around lightly. This game, however, certainly deserves the moniker. Playing the game will easily take up to three hours, not including a pretty intensive setup and teardown. This is one of those event games that you’ll need to block off a considerable chunk of your day to accommodate. After all, one does not just simply walk into a game of War of the Ring.

The Great Battle of our Time:

Upon first glance War of the Ring looks like, well, a war game. It has all the trappings of a traditional war game that you’d expect: armies moving around the map, traversing through defined territories, attacking and defending towns, cities, and strongholds. However, calling War of the Ring simply a war game is as reductive as calling The Beatles “those British guys.” Technically true, but like the Fab Four there is so much more to it than that. War of the Ring has a lot going on, so I’ll just channel my inner Paul McCartney and try to hit the high notes.

War of War of the Ring is an asymmetrical 2-player game where one person controls the evil forces of Sauron, called the Shadow, while the other plays the Free Peoples – the “good side” narratively speaking. While there are technically rules for multiplayer, like challenging a cave troll to an arm-wrestling contest, I highly recommend against it.

War of War of the Ring is an asymmetrical 2-player game where one person controls the evil forces of Sauron, called the Shadow, while the other plays the Free Peoples – the “good side” narratively speaking. While there are technically rules for multiplayer, like challenging a cave troll to an arm-wrestling contest, I highly recommend against it.

How to Win: War vs Will

Either side can win via a military victory. At the end of a round, the Shadow Player (SP) must control enough of their opponents’ settlements (cities or strongholds) to total 10 points, while the Free Peoples (FP) need only hold 4 points worth. The drastic difference in value is primarily due to two factors: The SP starts with a monstrously greater number of forces. Additionally, when the SP loses units in battle they go back to the reserve and can be brought back on future turns—you can always spawn more orcs. When the FP’s units die, they’re gone forever, lost to the annals of time.

The second victory condition involves the more canonical element of the “one ring.” If at any time Frodo reaches the final space of Mt. Doom, casting the ring into the fire, or if he becomes too corrupted by said ring, the game is instantly over, with either the FP or SP respectively emerging triumphant.

How to Play:

Each round is divided into six phases.

- Recover the action dice and draw two new event cards.

- Fellowship Phase: The FP can choose to declare the location of the fellowship, allowing them to potentially activate a nation, heal corruption damage, or change out their guide.

- Hunt Allocation: The SP can dedicate a number of action dice to hunting the fellowship.

- Action Roll: Players roll their action dice. Any “eye” result rolled by the SP is added to the hunt box.

- Action Resolution: This is the meat of the game. Players take turns activating dice to do the action listed on that die face.

- Victory Check: If either player has done enough to meet the military victory condition, the game is over. If not, rinse and repeat.

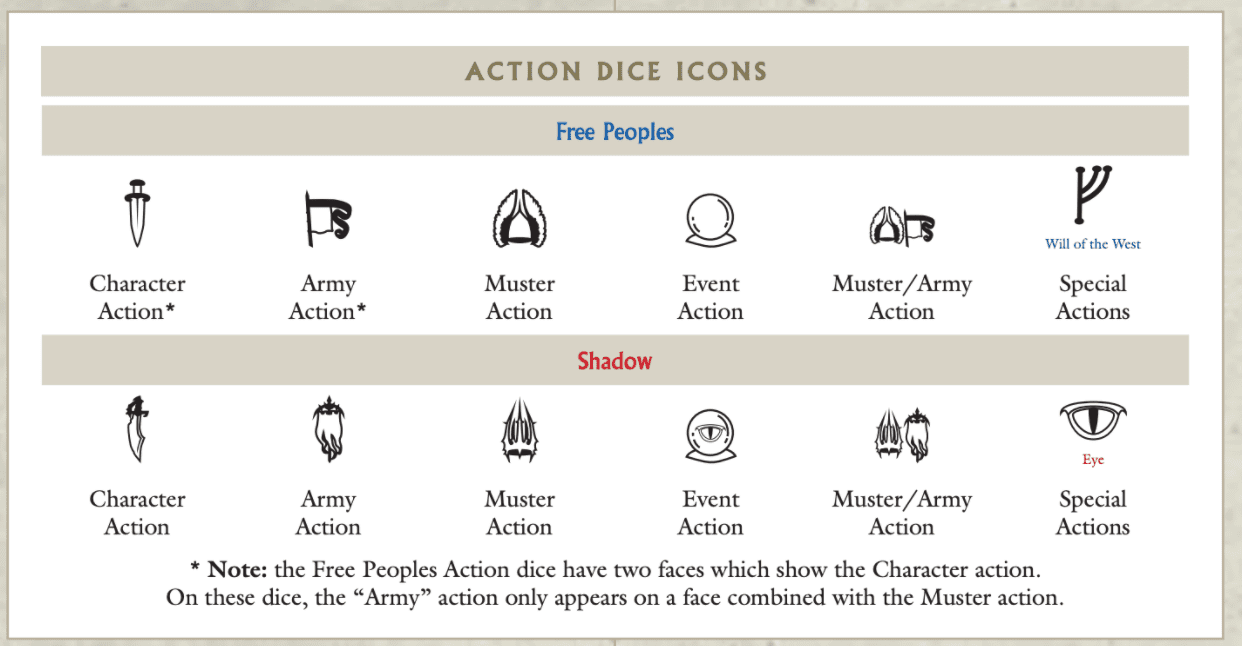

I’m not going to get too deep into Fangorn Forest’s weeds when it comes to each element, as there are a TON of moving parts. I will briefly touch on the Action Dice, since that is the bulk of the game.

Character Action: Move armies that contain a leader, move the special characters (Companions for FP, Minions for SP), or play a Character Event Card. FP can also use this action to move, hide, or split up the fellowship.

Army Action: Move armies, Attack an Enemy Army, or play an Army Event Card

Muster Action: Move one nation down the Diplomatic Track (more on this later), recruit Reinforcements, or play a Muster Event Card

Event Action: Draw an Event card, play an Event Card

Special Actions: The FP’s “Will of the West” is a wildcard that can be set to any other face, while the SP’s “Eye” is added to the hunt box. (more on hunting later)

More Key Concepts

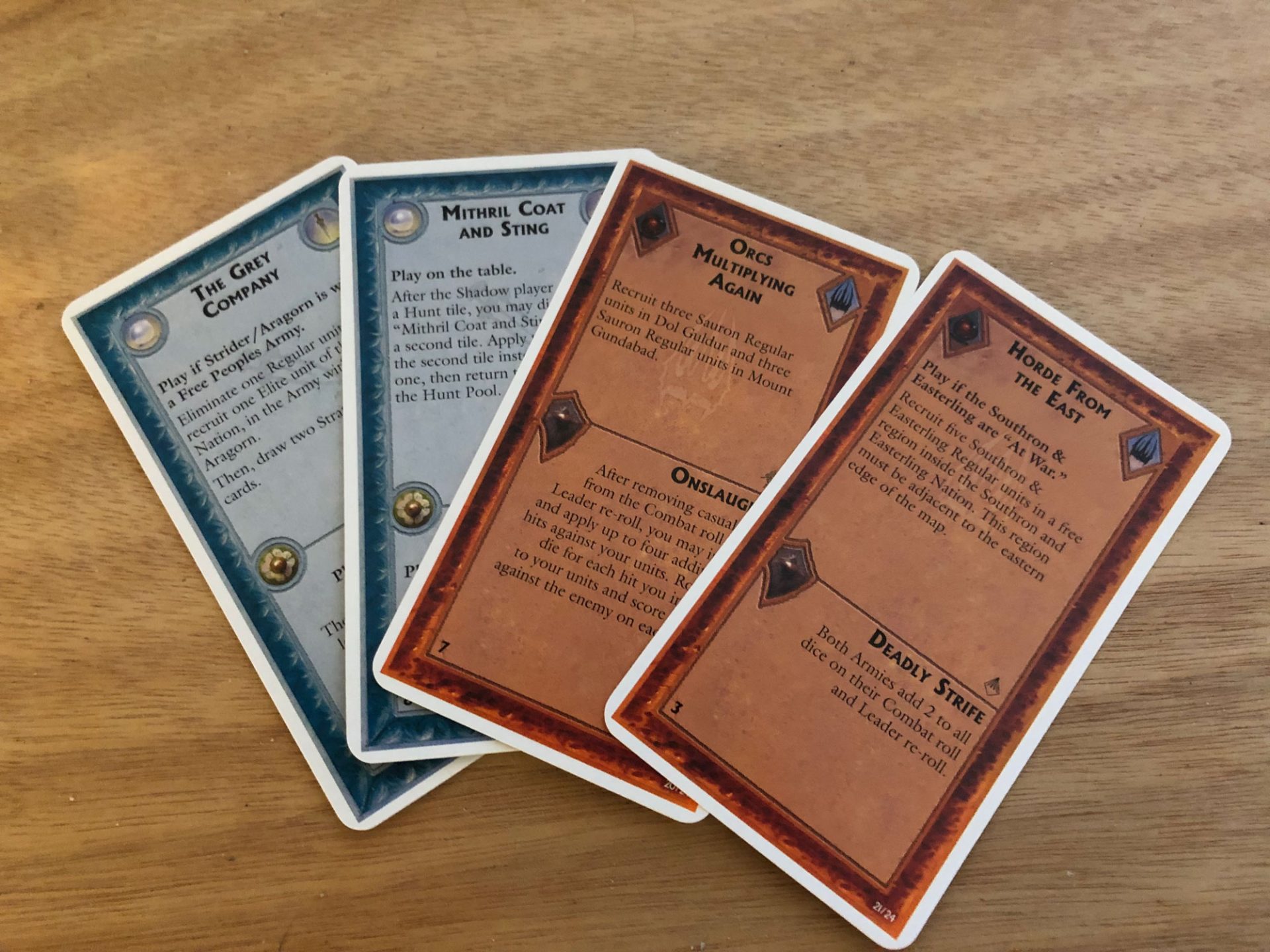

Event Cards: Each player has two different decks of cards, Strategy and Character. Each event card has symbols matching one or more of the above die faces, so they can be played with either the Event Action, or the Action matching the symbols on the cards. The event cards are highly thematic and usually entail some kind of bonus action, although there are some that may be situational or have an ongoing effect. Many of them can alternatively be used during combat. Deciding best how and when to play the event cards may turn the tide for either side.

Diplomatic Track: Will Rohan answer when Gondor calls for aid? Do the Southrons and Easterlings bring their boats and beasts? That all depends on the Diplomatic Track. At the beginning of the game, nations start at differing spots on the track and must be convinced to join the fray, either by the aforementioned Muster action, the FP declaring their location in a particular city, or other situational criteria as the game develops.

A Hunting We Will Go

One narrative strength of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings universe is that underneath all the grand gilded garrisons of a war epic is the simple story of two buddies going cross-country to return some jewelry. The importance of the “little guy” amidst worldwide chaos was never lost on the author, demonstrably having Frodo and Sam, two mostly normal Middle-Earth hillbillies, being the primary protagonists. War of the Ring stays true to this ethos. While navigating international diplomacy and managing military might is crucial to survival, we can’t forget that the quest is still about the ring.

This is highlighted superbly in War of the Ring by the game mechanics of moving the Fellowship. While we know canonically that the party starts at Rivendell, the journey that the Fellowship takes is primarily in secret. This is accomplished by a very clever set of mechanics.

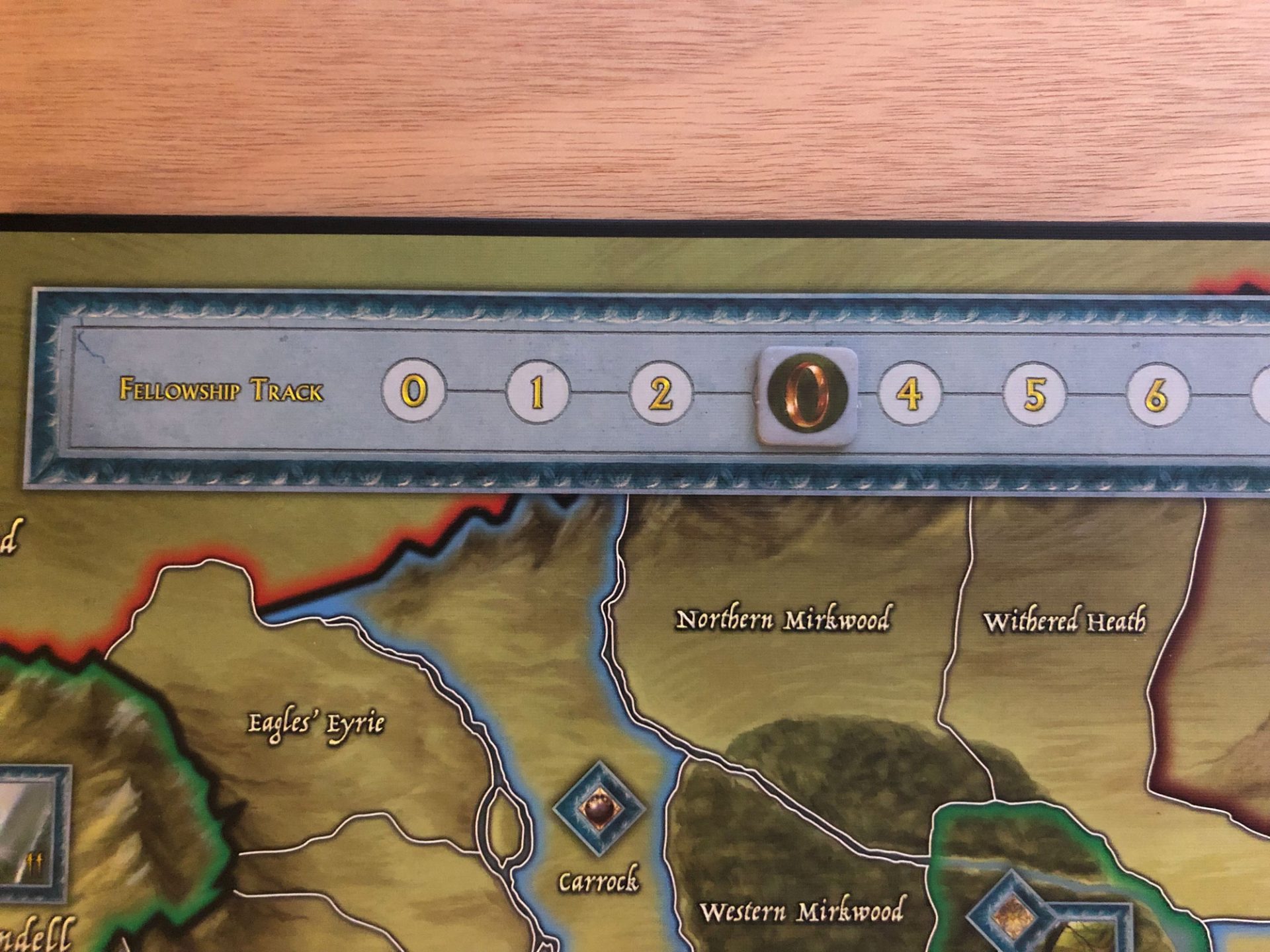

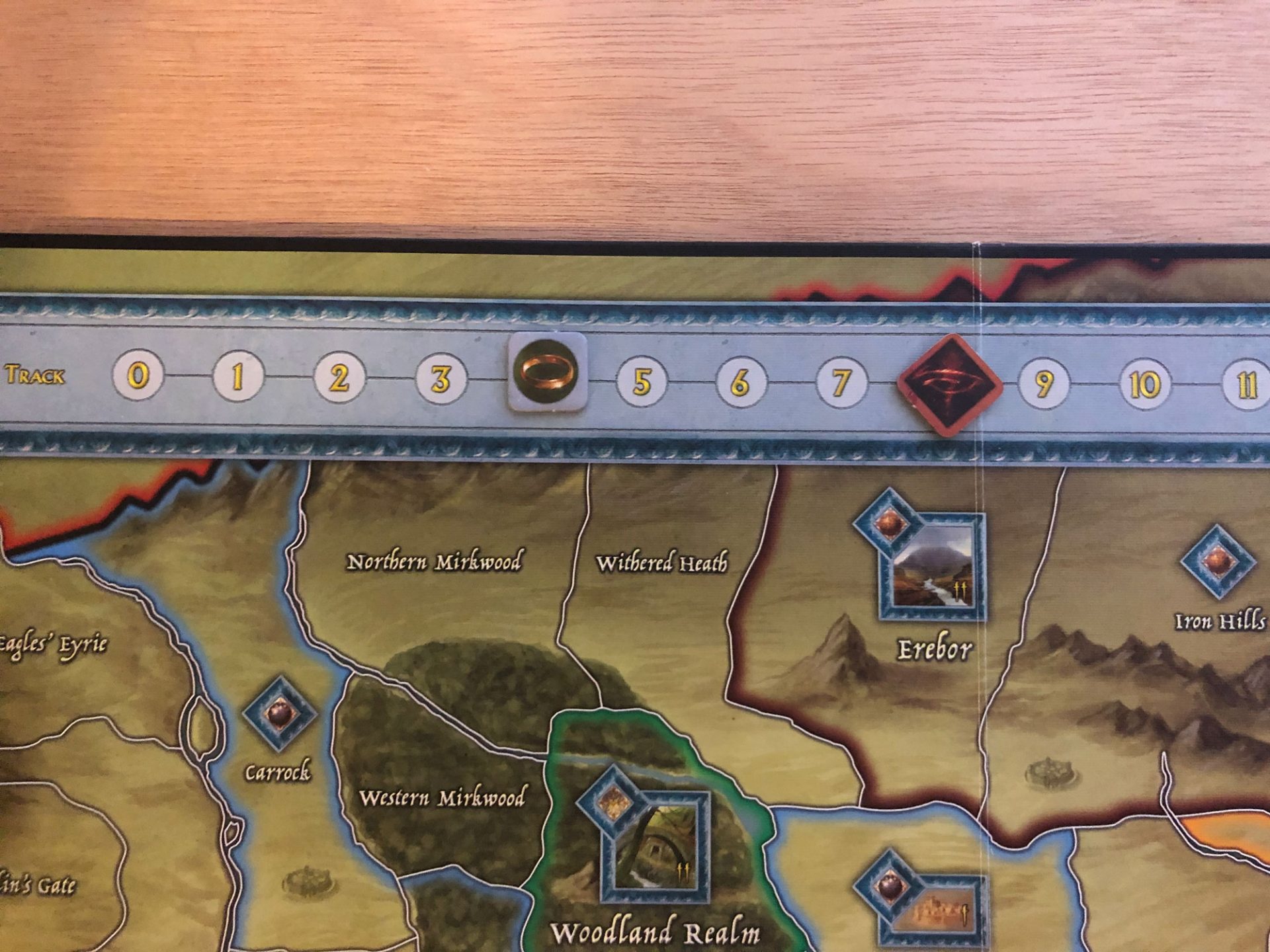

During the “Action Resolution” phase, the FP may spend one of their “Character Action” die results to move the fellowship, representing this by moving the Fellowship Track up one space. The miniature representing the fellowship does not move from its present location, we just know that it has moved one space. Any time the Fellowship is revealed, either by choice or consequence, they then move their figure the number of spaces on the Fellowship track, then reset that track back down to zero.

Every time the Fellowship moves, a “Hunt for the Ring” ensues, with the SP rolling a number of dice to try to catch them. The number of dice, or “Hunt Level” is equal to however many SP action dice are currently in the “Hunt Box,” comprising any “eye” results rolled and any dice specifically allocated in the “Hunt Allocation” phase 3. If the SP rolls even one ‘6,’ the hunt is successful and bad things happen. (more on that later)

Here’s where the integration of theme and mechanics really shine. The FP can move the Fellowship as many times as they have Character Action dice, but doing so gets riskier because each die they use to move is then added to the SP’s Hunt Box. Each of the FP’s dice in the Hunt Pool reduces the to-hit requirement by one pip.

So if the FP decides to move the Fellowship a second time in a round, the SP then only needs to roll a “5” the second time around to be successful. Going a third time, like hiring Gollum as your sous chef, is even riskier.

Deciding whether the risk is worth the reward is a devilishly difficult decision space. So what happens if the SP hunt is successful? The SP then draws a tile from a collection of nasty face-down tokens in the Hunt Pool to determine how much damage is done to the Fellowship.

The FP must then deal with that damage in one of two ways:

Reduce the amount of damage by “taking a casualty,”—yes, literally sacrificing a Fellowship member. (RIP, Boromir). Additionally, if the total damage is more than than that character’s strength, the remaining damage must either be taken by the next member, or as corruption. (described below)

Alternatively, instead of taking character damage, the FP can use the “one ring” to escape. The downside of that stealthy escape is that Frodo then takes on corruption, moving the corruption token up the Fellowship track. If at any point that track hits 12 corruption points, the SP immediately wins. 12 points of corruption is not a large margin, considering that a single token could deal you a whopping three points of damage. Mitigating and managing the Fellowship’s corruption level is a delicate tightrope act, or if you will, it is “balanced on the edge of a knife. Stray but a little, and it will fail, to the ruin of all.”

There are a lot more rules that I could go into, including the nuances of combat, siege craft, specific units, card play, etc, but for the sake of time, I won’t. Suffice to say, this game has a lot of interworking elements that will have you balancing multiple spinning plates while dancing a jig atop the tables of the Prancing Pony with a “yes, it comes in pints”-worth of both strategy and tactics.

The Wise Speak Only of What They Know – Final Thoughts

War of the Ring has frequently been billed as “Lord of the Rings in a box.” As a big fan of Star Wars: Rebellion—another such “franchise in a box” game—I was eager to see if War of the Ring would live up to the title. I’m happy to report that, by Galadriel, it did. I felt like I was playing out the Lord of the Rings trilogy. Whether I’m storming the Black Gates with Aragorn and company, tracking down the hobbits with the Witch-King astride his mighty Nazgul, or taking the hobbits to Isengard, every bit of this game feels like Lord of the Rings. In about the amount of time that it would take to watch one of the movies, you will feel like you’ve gotten your second breakfast’s fill of Middle-Earth.

I will mention one siege tower-sized oliphaunt in the room: the element of randomness. In the world of board games, I’ve found that there are two kinds of randomness: input randomness and output randomness. Put simply, input randomness determines your options, while output randomness determines your outcomes. War of the Ring has a decent-sized level of both. For example, the action dice that you roll at the beginning of each round demonstrate input randomness. You’re limited to the options rolled, although the fact that die faces can be used in multiple ways, plus the fact that the Free People has a wild die, slightly mitigates this. However, aside from some potential card play, there is very little mitigation to the output randomness of key elements like hunt token draws, combat rolls, and card draws. For me, this element of the unknown makes it thematic and memorable. Sometimes against all odds, a small force of Rohans at Helm’s Deep can stave off waves of charging Uruk-Hai. But I can understand how other gamers who prefer the strategic over the tactical may find this frustrating.

Overall, War of the Ring is quite simply a masterpiece. The choices are deliciously agonizing, the battles memorable, and the card play clever. It is equally gratifying playing as the Shadow Player or the Free Peoples. This is a fantastically designed game that is as rich as Smaug in theme. Every card and character ability make sense thematically. Gandalf can lead the Fellowship through the mines of Moria, Strider can leave the Fellowship to go level up and become Aragorn, Boromir can be heroically sacrificed to save the hobbits from taking damage. Everything that you would want to do in a Lord of the Rings game, short of finding out what was in that pipeweed, you can do. The only minor quibble I would have with the game is regarding some production quality issues. The miniatures aren’t the highest quality and some of the tokens can be difficult to decipher at a glance, but even this is easily forgivable considering the incredible scope and size of the game as a whole.

After a couple plays of War of the Ring, it galloped like Shadowfax straight into the pantheon of “games I don’t get to play often but will never leave my collection,” along with such heavy hitters like Star Wars: Rebellion, Twilight Imperium: Fourth Edition, and Star Trek: Ascendancy. This is an amazing game that I would recommend to any fans of Lord of the Rings or just epic gaming experiences in general. If indeed “all we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us,” then give me three or four more hours and I’ll play War of the Ring: anytime, anywhere, short of Shelob’s lair. It’s an easy 10/10.

Add Comment