In 1990, a few game designers were on the road to GenCon talking about the ideas they were working on. They had just formed a fledgling company and were looking for something big. They hit upon the idea of a series of games all connected by a shared universe and a genre that had only had its surface scratched – gothic horror. The game that came out of that car ride would go on to define role-playing gaming in the 1990s, Vampire: the Masquerade. With its revolutionary Storyteller system and a mythos that captured the angst of a post-80s generation of teenagers, Vampire (along with the other World of Darkness titles) became as iconic as Dungeons & Dragons, including its own brush with public infamy.

So, grab your crushed velvet bag of ten-siders as we sink our teeth into Vampire: the Masquerade.

Backstory

Vampire: the Masquerade began as the brain child of Mark Rein-Hagen, a game designer who had co-developed a previous game called Ars Magica at his company Lion Rampant. It was a very unique look at using magic to manipulate the world of medieval Europe and had a decent following including a fanzine called White Wolf (after Michael Moorcock’s Elric series). The two brothers behind White Wolf became friends with the team at Lion Rampant and eventually both companies merged into White Wolf Publishing.

In the now-legendary car ride to GenCon, Rein-Hagen, along with Stewart Wieck and Lisa Stevens (now CEO of Paizo) envisioned his connected series of games that would become the World of Darkness. He wanted to evoke the same gothic horror he had felt years before when he played the original Ravenloft module for Dungeons & Dragons. Written by Tracy & Laura Hickman, Ravenloft tells the story of Strahd von Zarovich, a vampire whose loss of his true love has plunged his world into darkness. It was unlike any other D&D module before it in that there was atmosphere, emotion, and a sense of fate to the story it told.

The World of Darkness

The story itself follows the Kindred, vampires who hide in and from the modern mortal world behind The Masquerade, a tightly-held tradition (among some) that their existence must remain secret at all costs. This has gone so far as to become a complex conspiracy maintained by the worldwide organization known as The Camarilla. Through its power and influence, the Camarilla manipulates the mortal world to maintain the Kindred’s secrecy even for those who believe the Camarilla to be stodgy and outdated.

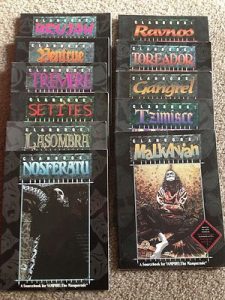

In the core game, the Camarilla is run by seven clans of Kindred. All of them, bloodlines descended from the first vampire, the biblical Cain, who was cursed by God to roam the Earth forever. Each clan has its own unique traits that cover some of the traditional vampire stereotypes. The Nosferatu clan is disfigured and able to move about unseen much like Max Schrek’s classic character. In contrast, the Toreador clan are the epitome of immortal beauty and can create a sense of awe in a mortal much like Anne Rice’s Lestat. From a game mechanic standpoint, the clans provide a character archetype so that a player can choose a physical, combat character like a Brujah or a more intrigue-focused, political character like a Ventrue. Their abilities could be augmented (adding dice to a dice pool) by using blood points which were regained by feeding on mortals.

In the core game, the Camarilla is run by seven clans of Kindred. All of them, bloodlines descended from the first vampire, the biblical Cain, who was cursed by God to roam the Earth forever. Each clan has its own unique traits that cover some of the traditional vampire stereotypes. The Nosferatu clan is disfigured and able to move about unseen much like Max Schrek’s classic character. In contrast, the Toreador clan are the epitome of immortal beauty and can create a sense of awe in a mortal much like Anne Rice’s Lestat. From a game mechanic standpoint, the clans provide a character archetype so that a player can choose a physical, combat character like a Brujah or a more intrigue-focused, political character like a Ventrue. Their abilities could be augmented (adding dice to a dice pool) by using blood points which were regained by feeding on mortals.

Story campaigns were mostly centered around a city (many times the players’ own city) and the hidden forces at play within the city. Being set against the real world meant that Storytellers could create stories based on what was around them and current events. This meant that they didn’t need to buy campaign setting books, making for another easy point of entry.

Individual games within the campaign would deal with the characters’ power struggles. Having lived long past mortal standards, Kindred have cultivated their areas of influence and resources at their disposal which they would attempt to use to accomplish goals. Sometimes it would be to protect a breach of the Masquerade, other times it would be to ensure that the Gangrels and Brujah were not about to have a gang war, or other times it would be to get that new business venture off the ground without a hitch. Play generally focused on politics and intrigue with combat being a last resort. However, other groups of Kindred (and sometimes other less-familiar clans) would encroach on the Camarilla’s domain and must be put down at all cost. Later, player options would allow for campaigns involving those groups and their conflict against the Camarilla.

Individual games within the campaign would deal with the characters’ power struggles. Having lived long past mortal standards, Kindred have cultivated their areas of influence and resources at their disposal which they would attempt to use to accomplish goals. Sometimes it would be to protect a breach of the Masquerade, other times it would be to ensure that the Gangrels and Brujah were not about to have a gang war, or other times it would be to get that new business venture off the ground without a hitch. Play generally focused on politics and intrigue with combat being a last resort. However, other groups of Kindred (and sometimes other less-familiar clans) would encroach on the Camarilla’s domain and must be put down at all cost. Later, player options would allow for campaigns involving those groups and their conflict against the Camarilla.

The Storyteller System

For the mechanics behind Vampire, Rein-Hagen would turn to Tom Dowd, the developer of a recently released, highly-praised system, Shadowrun. Shadowrun had come out the year before and taken the basic “additive” dice pool system of games like Star Wars: the Roleplaying Game and built something new – a “comparative” dice pool. In the comparative dice pool system you still have a number of dice rolled against a difficulty rating. But, rather than add them up to see if that rating is overcome, you see how many of the dice are equal to or greater than a given number. For example, you might roll three dice against a difficulty of 4. If you rolled a 3, 4, and 5, you would have two successes. The number of successes determines how well you succeed at your task.

In Vampire, that comparative dice pool used 10-sided dice and became the basis of the Storyteller System. The Storyteller System was designed to allow the players and Storyteller (the White Wolf word for Dungeon Master or Game Master) to collaborate and determine how their characters interacted with their world. In the example above, the two successes would be used to determine how well the character accomplished a task. They succeeded, but to what extent? Was there a slight misstep or was the task so trivial that two successes would make easy work of it? The group told the story together. Compared to the most popular RPG at the time, Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (or even its spiritual predecessor, Shadowrun), Vampire’s rules were extremely lightweight and allowed for an easy entry point.

In Vampire, that comparative dice pool used 10-sided dice and became the basis of the Storyteller System. The Storyteller System was designed to allow the players and Storyteller (the White Wolf word for Dungeon Master or Game Master) to collaborate and determine how their characters interacted with their world. In the example above, the two successes would be used to determine how well the character accomplished a task. They succeeded, but to what extent? Was there a slight misstep or was the task so trivial that two successes would make easy work of it? The group told the story together. Compared to the most popular RPG at the time, Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (or even its spiritual predecessor, Shadowrun), Vampire’s rules were extremely lightweight and allowed for an easy entry point.

Additionally, Kindred can use the blood (or Vitae) that courses through their veins to accomplish supernatural feats. This is represented by Blood Points that can be spent to augment rolls or fuel their clan-specific powers. As a Kindred’s supply of Vitae dwindles, their hunger takes over and they must feed. If they ignore it, the beast within them takes over and they frenzy like a wild animal (most likely breaking the Masquerade in the process).

Reception

The first edition of Vampire was released in 1991 with the classic green marble cover and interior art by Tim Bradstreet. Its themes often included humanity, mortality, sanity, politics, and ambition. Hitting at the exact time as counter-cultural movements like grunge music, Vampire’s gothic-punk atmosphere capitalized on the wave of postmodernity at the time and brought in many new role-players who found something familiar. It won the Origins Award for Best Roleplaying Rules of 1991. A second edition followed closely in 1992 with mostly cosmetic changes to the rulebook and minor tweaks to the rules.

After Vampire’s success came other titles in the World of Darkness like Werewolf: the Apocalypse and Mage: the Ascension. All were set in the same world but with different viewpoints. For example, the Werewolves (or Garou) sought to destroy the vampires as they were agents of corruption and would bring on the Apocalypse.

As the decade progressed, the goth and industrial music movements provided the perfect soundtrack while film explored similar themes with Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Interview with the Vampire, and Blade. In 1996, a short-lived television series based on Vampire called Kindred: the Embraced was even produced. Vampires were in the dark corners of everyone’s minds. Because of this counter-culture, players were often already dressing and sometimes acting like vampires. Why not combine it with their game? This led to a new way to play the game, not through pencils and dice, but through acting. Modern live action role-playing (or LARPing) had been around since the mid-70s, shortly after Dungeons & Dragons was published, but was almost always fantasy-based. It was also played outside in remote areas (mainly due to the need to spread out when fighting with prop weapons!).

As the decade progressed, the goth and industrial music movements provided the perfect soundtrack while film explored similar themes with Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Interview with the Vampire, and Blade. In 1996, a short-lived television series based on Vampire called Kindred: the Embraced was even produced. Vampires were in the dark corners of everyone’s minds. Because of this counter-culture, players were often already dressing and sometimes acting like vampires. Why not combine it with their game? This led to a new way to play the game, not through pencils and dice, but through acting. Modern live action role-playing (or LARPing) had been around since the mid-70s, shortly after Dungeons & Dragons was published, but was almost always fantasy-based. It was also played outside in remote areas (mainly due to the need to spread out when fighting with prop weapons!).

This new play style was something different – it could be played in homes, coffeehouses, clubs, or even out in the street. White Wolf sensed the growing popularity of this variant on their game and in 1993 published the first book in their Mind’s Eye Theater line of rules for LARP. It, of course, was for Vampire.

Mind’s Eye Theater (especially Vampire) is the best example of where LARP almost eclipsed the pen-and-paper game. Its rules were extremely lightweight, allowing the acting and improv to take center stage. The setting and story were exactly the same as the tabletop game, making the two games interchangeable. The outcome of this was that for many, playing Vampire became synonymous with LARP. Organized groups sprung up worldwide and an official LARP society sanctioned by White Wolf was formed. The game grew very rapidly in a short amount of time and gathered much attention, both wanted and unwanted.

Conservative religious groups became aware of a “new threat” from those role-playing games. The misconceptions about Dungeons & Dragons in the 80’s, specifically that you wore costumes and made dealings with evil things, were actually happening this time! The biblical connection only made the evidence greater. The reaction was starting to be seen as ridiculous after these same groups had come out against many other pop culture targets. But, in 1996 it took a deadly turn. A married couple in Florida were murdered and the killers were a group of teenagers that were reportedly obsessed with Vampire.

Aftermath, Decline, and Gehenna

White Wolf came out of this incident relatively unscathed partly because its base of players were not generally affected by public opinion and continued to support the company and the game. But White Wolf started to experience trouble in other places.

The company would go on to expand the Vampire line. Additional Kindred clans were introduced. Each clan now had its own sourcebook, and there was even a historical offshoot that allowed campaigns in the Dark Ages. As with many RPGs in the 80s and 90s, the game was starting to crumble under the weight of its own supplements. A 3rd edition with revised rules came out in 1998 to address some of the rules conflicts and to incorporate some of the more popular additions into the base game. This held off Vampire’s collapse but the other games were not maintaining the same level of success.

The company would go on to expand the Vampire line. Additional Kindred clans were introduced. Each clan now had its own sourcebook, and there was even a historical offshoot that allowed campaigns in the Dark Ages. As with many RPGs in the 80s and 90s, the game was starting to crumble under the weight of its own supplements. A 3rd edition with revised rules came out in 1998 to address some of the rules conflicts and to incorporate some of the more popular additions into the base game. This held off Vampire’s collapse but the other games were not maintaining the same level of success.

White Wolf’s product line had grown too big and some of their later attempts to add interesting ideas to the World of Darkness failed. These lines would need to be discontinued and even their mainstays needed to be refreshed. So, in 2004, the World of Darkness came to an end. In each of the core games, the Time of Judgment came. Every game had its own metagame take on the end of the world. For Vampire, it was the mythical Gehenna when the ancient Kindred (and Cain himself) would awake and wage war on their offspring. And so, each product line ended with its own adventure module that brought the World of Darkness to an end.

After the cataclysmic ending to Vampire: the Masquerade, White Wolf continued on with reboots, was purchased, killed off, and much like its creation, rose from the dead. There is currently a Fifth Edition of Vampire: the Masquerade now in print. But that is a story for another time…

Final Thoughts

As a role-playing gamer born in the late 70s, D&D was my childhood and Vampire was my angsty teenage years. I was a high school freshman when the second edition came out. By my freshman year in college, I had found a local Mind’s Eye Theater troupe. The goth/industrial scene was a huge part of those years and Vampire was very much entwined. Though I am much older now, I still have a fondness for the Storyteller System and its streamlined elegance. Its influence can be seen in much of the modern narrative RPGs.

As a role-playing gamer born in the late 70s, D&D was my childhood and Vampire was my angsty teenage years. I was a high school freshman when the second edition came out. By my freshman year in college, I had found a local Mind’s Eye Theater troupe. The goth/industrial scene was a huge part of those years and Vampire was very much entwined. Though I am much older now, I still have a fondness for the Storyteller System and its streamlined elegance. Its influence can be seen in much of the modern narrative RPGs.

That being said, as with much of childhood, the classic World of Darkness setting is starting to feel dated. Though it was written to be played in the “modern world” it was the “modern world” of the 90s. An update is definitely needed and one has recently become available. But, does it rise to the occasion?

Stay tuned for our review of Vampire: the Masquerade, Fifth Edition!

Electronic versions of all editions of Vampire: the Masquerade as well as the other World of Darkness games can be found at DriveThruRPG.com.

Add Comment