Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

Disclosure: Meeple Mountain was provided a pre-production copy of the game. It is this copy of the game that this review is based upon. As such, this review is not necessarily representative of the final product. All photographs, components, and rules described herein are subject to change.

One of my crotchety opinions is that, like racing, the concept of “adventuring” doesn’t often translate well to board games. The latter function as systems that often help us think about other systems, and adventure isn’t really a system, at least, it’s not a feeling or an idea that can be easily transmogrified.

The gold standard for adventure games, in my book, is Mario Papini’s De Vulgari Eloquentia, a game where you wander around Italy collecting books to create a language. While this isn’t exactly swashbuckling, it captures how hard it was to just move around in the early modern era. Crossing an ocean? Forget about it. Every decision in DVE is built around a simple question: you can do it, but do you have the horses? Tension, consequences, and stakes–that’s what an adventure needs.

Like DVE, The forthcoming Ultimate Voyage (Final Quest of the Treasure Fleet) is a resource management eurogame that’s got its hiking boots on. Ultimate Voyage continues the trend of not exactly being a game that feels like adventuring, but it does have some novel mechanisms that blend together in new and interesting ways. As far as mapping new horizons for the genre, it makes some interesting, if slightly staid efforts.

How to Voyage

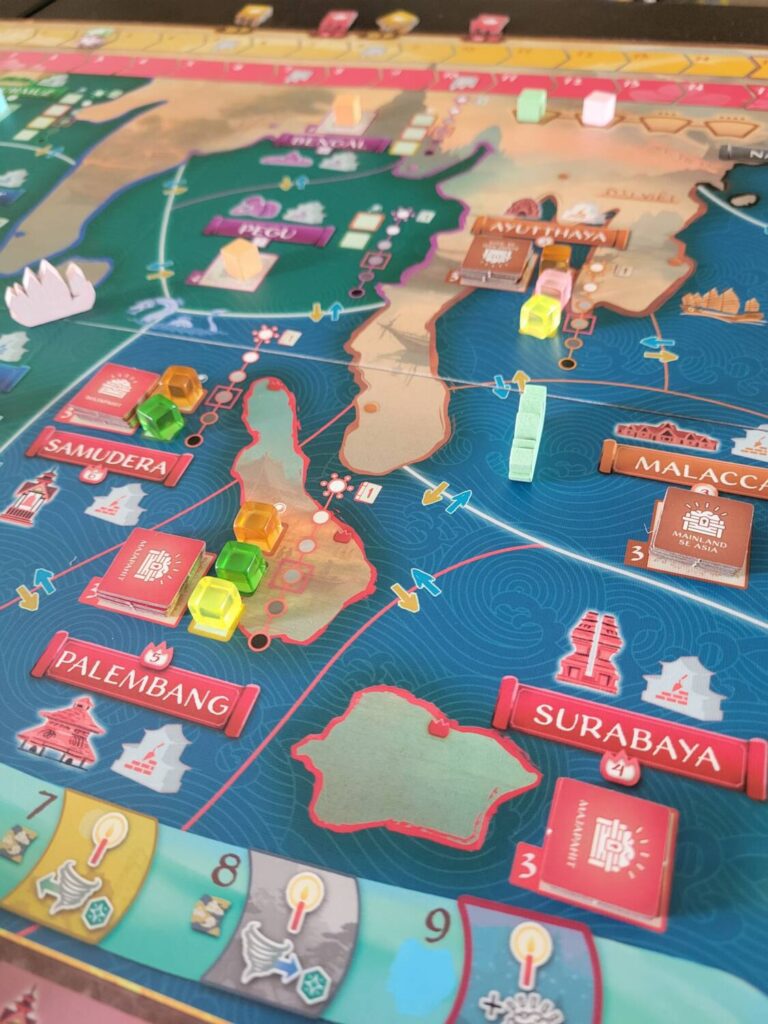

In Ultimate Voyage, you’re headed back to Ming China, where you’re teaming up with Admiral Zheng He to trade, fight, explore, build, and conduct diplomacy with the territories that once composed the Ming tributary system.

Mechanically, you’re trying to get victory points. You have two tracks, Prestige and Profit, which, in Knizia style, you’re only going to score the lowest of at the end of the game. You’re going to get points for a mess of other things as well, but the tracks are the big scorers. Much of what you do in the game is going to move you up one or both.

On your turn, you have a row of cards above your player board, representing 5 actions. If you’ve played Ark Nova or Civilization: A New Dawn, you’ll recognize this system. The “strength” of an action is equivalent to its position in the row of 5. The card farthest to the right has a strength of 5, and farthest to the left is 1. Unlike the two games I just mentioned, you rotate a card after you use it, and its strength is 0 if you want to use it a second or third time. You are also limited by your deity tokens, which are tokens that have their values set randomly by a dice roll at the beginning of a round, and you combine with your card strength for a strength total. You can also spend the two resources in the game, armies or pots (or for some actions, both) to increase the strength of your actions. Most of the time, you’ll be doing three actions per round.

The actions range from complex to simple. Movement is defined by the way the wind is blowing. When you move, depending on if the round is yellow or blue, it’s more or less expensive to travel along the blue or yellow arrows connecting areas on the board. With the wind at your back, you can zip around the entire thing. Otherwise, you’re slugging along—I love a system like this. Each of the cities on the board has a stack of trade tokens that you’re trying to collect with a Trade action for track moves and other goodies, and they all have their own strength rating, which interacts with several different actions to determine the degree of success.

Cities have an Affiliation rating, which is initially randomly determined, but you can throw the Diplomacy action at them to advance affiliation to higher and higher levels, and once you get it to the top, it becomes your tributary, which gets you some points and other players can no longer attack that city. Combat functions similarly to diplomacy, except with dice rolls against un-tributaried cities.

Enough fine print, let’s talk encounters

Overall, the primary mechanisms of the game are solid, and while they have more rules grit than I typically like in a game like this, you can get moving with everything and it does feel dynamic. Affiliation ratings dip over time, you have to deal with a Mongol invasion (mostly a die roll), and there are storms that appear on the oceans that you can get rewarded for sailing through successfully.

Now, encounter cards. Ugh. When you sail into a new area, you draw an encounter card, which resembles the encounters in Scythe, you have a suite of options, and you choose one and take rewards and/or penalties. I don’t enjoy systems like this. They are unresponsive to what players are doing in the game, and they often don’t distribute rewards equitably among players. The ones in this game are relatively mild, but I’m not sure the game needed these cards. But, if you like this sort of RPG-lite-choose-your-own-adventure sort of thing, I doubt you’ll be offended.

There are several game end conditions: a player maxing out both of the scoring tracks, Zheng He dying, 9 rounds elapsing, or a player completing 4 objectives (which sit in a display above the board and are another way of accumulating points). Points come primarily from the tracks, but you also get some points for engaging with a pick-up-and-deliver mechanism where you lose a ship to build a Porcelain tower, and there are points to be gained from individual eurogame “who is highest on the track” tracks for each individual region in the game.

A venture

Ultimate Voyage was not a disappointment, and while it didn’t capture the breathless feeling of adventure that some of my favorite games of this ilk do, I still found it to be an enjoyable time. If you go in expecting to have a rip-roaring adventure, you might be disappointed, but there is still joy to be found engaging with its economy, which has an interesting pulse to it. It will be on Kickstarter soon, and I look forward to more games and ideas from this studio. If you’re a fan of adventure games that lean more toward the non-confrontational euro-side of things, you’ll find a lot to like here.