Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

[Disclaimer: I played this game a single time for this preview. (Normally, I complete a minimum of three plays before posting thoughts on a game like this, but our prototype version did not include the components required for solo and two-player games. My play took place with three players, using prototype components. This is a first impression, so please take this into consideration as you consider backing this campaign.]

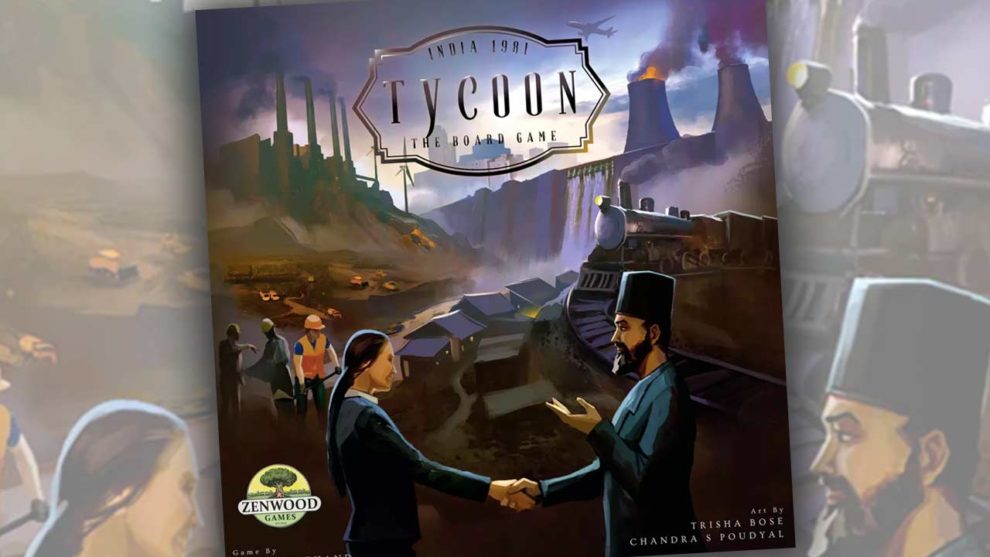

Based solely on the fact that Tycoon: India 1981 (Zenwood Games, coming to Kickstarter on August 29th) was designed, developed, drawn and distributed by a team that hails from India, the game is an incredible achievement.

I don’t think I have played a single game since joining Meeple Mountain that was designed by a person of Indian descent. In and of itself, I find that mind-boggling, given the sheer population size. But that also means this is an opportunity.

So I’m going to seize it. If you are on the fence about whether to support Tycoon: India 1981, but want to support a small minority-owned publisher and are finding few options to do so this year, please give this game a look. The game has real flaws, and I’m going to call those out in this preview. Knowing that most of the prototypes I cover change a bit between the development stage, crowdfunding, and final production, Tycoon: India 1981 may smooth some of its rough edges in time to make an average game into something much more interesting.

The bones are here. It was great to read some flavor text on cards about a time period in India that sounds like it was a real struggle—for its citizens, its industries, and its economy. Tycoon: India 1981 doesn’t do anything gameplay-wise that I would call unique, but its combination of Euro-gaming staples might warrant another look.

Favor Tokens

The game is an economic simulation of a historical period in a foreign land, featuring loans, industry tokens, building actions, and tracks with cards spread across two ages.

No…it’s not Brass. Instead, I’m describing Tycoon: India 1981, a 1-4 player economic simulation set in the back half of the 20th century, featuring tracks (moving up on sector tracks, not railway tracks), loans (and we’ll have to talk about the loan action a bit later), and industry tokens (in the form of houses that can be built on a map).

But you’d be surprised how often Brass came up during my single play of Tycoon: India 1981. That’s not because the game directly mimics any of the core gameplay elements of the Brass games. It’s because Brass is one of the gold standards of cutthroat industrial economic play. In a world where Brass exists, our play group usually gravitates towards Brass, an occasional 18XX game, even games like my pick for the year’s biggest surprise, East India Companies where a combination of elements are at play in a two-hour investment Euro.

So, in many ways, Tycoon: India 1981 has a tough row to hoe. Many of its elements feel like they were done significantly better in other economic games of the distant, and even recent, past. During a period in the game that begins in the late 1940s and speeds through the 1980s and 90s, players take on the roles of industrial barons looking to expand India in its post-colonialism period.

And, they’ll do that by rebuilding India from the ground up. The central element of Tycoon: India 1981 is the Tycoon power. In most rounds, this power is given to the player who bid the highest amount of cash for the right to select an Industry card from a face-up display of three Industry options in the previous round.

But for the first round of the game, the Tycoon power is given to someone during setup. Randomly.

ARE YOU ******* KIDDING ME? said my strategy brain when I first read the rules. IN A GAME WITH EXTREMELY LIMITED ACTIONS, ONE PLAYER GETS AN EXTRA ACTION SIMPLY BY WINNING AT CHWAZI???

This rule simply doesn’t work. One assumes that this design choice was discussed during playtesting; designer Sidhant Chand kept this choice in the prototype (rules were updated in early August on BGG), but I’ll be curious to see if it ends up in the final game. In Tycoon: India 1981, players only get two actions per round, with the Tycoon player getting a third action.

My two opponents howled when they watched our first round play out, seeing that I was gifted an extra action in the first of a seven-round game. In many ways, I am thankful I did not win, because I did have a somewhat juicy first round and I was feeling a little guilty.

How Does It Play?

Let’s talk about those rounds. Each one follows the same format. First, the Tycoon picks the active region for the round: the northern quadrant of India, west, east, or south. That pick grants a small bonus to each player with an industry building present. So, in the first round, not much to call out there. Then in phase two, a special event takes place: income (if you have any Industry cards in play) and dividend payments to shareholders. Then, a lot like the end of each round of Tinners’ Trail, players can buy points and favor with the Indian government by spending a good amount of their cash.

The other special event: Policy cards. These cards—one of which is picked for free by each player during setup—provide ongoing, end-game, or one-time bonuses to their owner. Players bid for these Policy cards by spending Promoters, the game’s term for a mix of the kinds of people who get things done in the real world—lobbyists, staff, passionate followers, social media (if this were a game that took place in the present).

Phase three is the most consequential phase of the game: industry bidding. Over the course of two bidding rounds starting with the Tycoon, players can bid on the three active Industry cards in the display. The top two bidders get a choice amongst those three cards, and the highest bidder becomes the Tycoon in the following round (not right away).

I quite like this third phase. Players bid funds secretly hidden behind a player screen; the top two players get the chance to take a card to build later in the action phase of that, or future, rounds. There’s always going to be something to build, and the losers in the bidding process still get Promoters to use for Strategy actions later, actions that include victory points (Influence), moving up sector tracks, grabbing extra action tokens, etc.

Industries are vital to one-half of the win conditions in Tycoon: India 1981—a player’s total asset value. Winning Industry cards, then building those industries on the game’s board (a 32-city map of India), gives players an asset value that provides permanent points plus some extras, like bumps up tracks, money, extra action tokens, and Influence points. Influence is the game’s other half of the win conditions; straight points, baby.

Actions in Tycoon: India 1981 feel like standard fare; adding Promoter resources to a pool to spend them on Strategy actions was the most interesting thing to do, but one could also use the minor bonuses on their Policy cards to gather scraps here and there by taking the Politics action. One can also buy shares in other corporations, but there are a few issues with this that could be solved by adding an asset value track inside of the score track, similar to (I promise, I won’t do this again) how the Brass games track points and income with two separate markers.

Share actions had another complication that I still can’t really center in terms of my position. Shares can be bought for 30-70 crores (the game’s monetary unit, which are worth roughly 10 million rupees). But those shares also cap out at a 10-crore dividend for owners. You can’t buy shares in your own company (a minor issue that some other games share to ensure you can’t hoard your own good fortunes).

But my main issue comes at the end of the game. I want to invest in the best companies…but I basically have to ask players throughout the game what their current asset value is. That’s because shares in the company with the highest asset value are worth the most points at the end of the game: 60 crores for the company with the highest asset value, then 40, then 20, then zero. If one player has a big lead in asset value, I’m only buying their shares, but it’s basically a secret who is running the best company without a stock market or a score tracker.

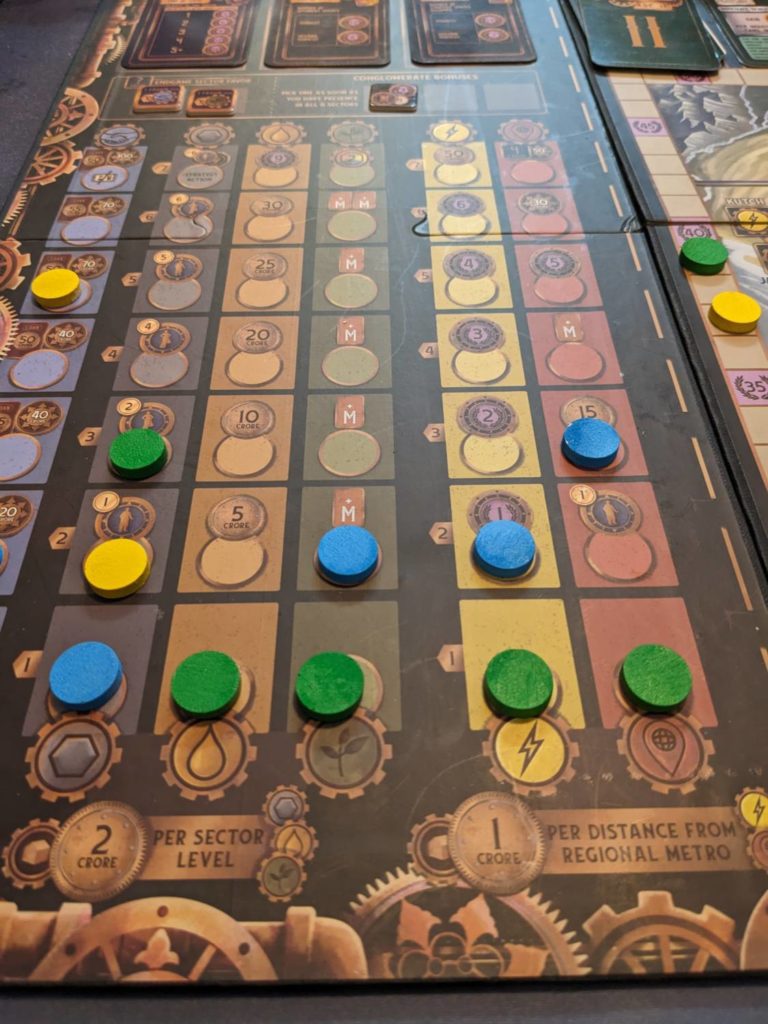

The most complicated action in the game is the Build action; it’s a bit more math-heavy than I’d like, but it’s not too complicated. Actually, this is another area of Tycoon: India 1981 that I really enjoyed; building costs are paid to the current leader on the tracks listed on the industry cards. So, driving up on the tracks that might pay out the most (minerals, agro, and fuel) became a fun pursuit for players in our game. I want others to pay me cash to build, so at least I’m getting a little sweetener while you build up your industry. And if I build industries with sector tracks where I am the current leader? I don’t have to pay anything.

OK, now!

So, What Worked?

That build action sequence ended up being something fun for our group. As I also mentioned, the industry bidding process was also something to like.

Playtime was shorter than I was expecting; this is a two-hour game with three players in the right hands. (Those hands are mine, because players in my groups rarely suffer from analysis paralysis.) That’s a good play time for a game of this weight.

Tycoon: India 1981 has plenty of the things that keep a Eurogamer like me warm at night. In addition to tracks (because everyone who loves Euros loves tracks), the tracks have a bunch of bonuses. Money bonuses, asset value bonuses, extra action tokens…the tracks are fun. You’ve also got public milestones (Planning Commissions), private milestones (Corporate Agendas), even little bonuses added to cards that were not drafted in previous rounds to sweeten the pot, a bit like Puerto Rico’s requirement of dropping a coin on the roles that weren’t taken in a previous round.

The player aids here are pretty good. Not perfect, because they don’t completely cover what all of the actions in phase four can do, and they are spread across the front and back of two large cards. But games like this need player aids and I like that they were included, even at the prototype stage.

What Didn’t Work?

Loans. Taking an action to take a loan feels off, particularly in a game with so few actions. Also, the game format is for a player to take a single action, then another player takes a single action, etc. In a game with loans, it would be great to set up a turn by taking a loan as an action, then taking a main action in succession.

I know I made a promise and am breaking it again, but other Martin Wallace designs, like Age of Industry and Railways of the World, push players to take loans all game long without stopping to take an action to do it. Using an action to take a loan is fine in a game that has lots of turns. Tycoon: India 1981 is basically a 14-action game; do I want to take three or four of those actions to take a loan??

The thing that really struck our group, though, is that loans are not punishing enough. In part, this is because of how the end of the game works: all players get one final round of income before end-game scoring. During this final income step, everyone pays off all of their loans, but your income is going to be pretty juicy at the end of the game.

Looking back, I should have taken 3-4 loans because other players were able to pay them off so easily. If this is the case, why are we forcing players to take actions to take loans? I’ve never, not a single time, heard another person across my 20+ years of gaming tell me that they loved taking loans in a game. “Oh man, the way loans work in this game? Magic.” No one has ever said that; loans aren’t fun in games, and they aren’t fun in real life either. They sometimes make games more interesting, but normally, loans get in the way of a good time.

(One game that handled loans well–last year’s Autobahn. Once per era, you could just get a big cash boost. It costs you an action, so the game is telling you that you need to be more efficient. But you don’t have to pay it back, and you can do it up to three times in a game with lots of actions. All good!)

Another loan oddity: “Emergency” loans can be taken at any time, but those loans only yield 25 crores, not 30-60 crores when taking the main loan action. Regardless of the loan amount received, a player always gets dealt a promissory note with a payoff rate of 50 crores.

Yes, this means you might take a 55-crore loan in Tycoon: India 1981 and only owe 50 crore later. I can’t think of a single game where the loan rate was higher than the payback rate.

Other things that could be improved? The game map. Yep, it’s India. But the game didn’t feel as Indian as I was hoping for. I’ve been to India twice and worked for a majority-Indian consulting firm for 12 years. I feel comfortable saying that I know India as a foreigner pretty well. Once the game got going, it didn’t really feel like I was rebuilding India.

I was sort of hoping for more historical context with specific entities; for example, the four player corporations appear to not be Indian conglomerates from the 1940s. The color palette doesn’t feel as bright as I was hoping for, with a layout that’s a bit more drab. The game doesn’t really change from Age I to Age II (in fact, this is my first mention of it because it doesn’t really affect gameplay), save for better cards in the Industry and Policy marketplaces.

Now, the flavor text on the cards does a great job of calling out specifics on change during this period in India. But you’ve got to focus on that text to really catch it all.

There are six action choices, but it always felt like players were taking the same 2-3 actions on their turn. One of those actions is always to build, if they have an unbuilt Industry card. If a player doesn’t have anything to build, it almost feels like they take the same two actions based on their cash position when their turn comes around.

Not scripted, per se, but things felt a little dry. I’m taking a loan on every turn when I don’t get a building in future plays, for example. Politics is going to be a choice if I’ve built and don’t have any money or Promoters left.

Right On the Line

Tycoon: India 1981 does more right than wrong, but it’s a game I can’t recommend…at least, not yet.

The random first-player assignment rule is unforgivable to me, and it’s the thing that would shock me the least if it is changed in its final state. Actions are extremely precious in Tycoon: India 1981, and just giving one to the first player for what amounts to rolling a die should be rectified.

I can’t speak to how the game’s final production will look, but as a prototype, I think Tycoon: India 1981 is better than some of the prototypes I’ve played in recent years. Better buildings for the plants, heftier action tokens, and different color choices for the promoter and favor tiles would all be appreciated. A higher and wider player screen would help also; as it is, using poker chips instead of the included cardboard chits made it a little too easy to see the tops of player assets from across the table. (Also, I’ve got big hands; these screens were difficult to navigate when trying to keep my stash of resources secret.

The lack of a stock market, or standard board-game economic simulation elements, are also a miss to me. Tracking other players’ asset value should be done the same way tracking scores works, and would lead to a better outcome.

Despite all of this, Tycoon: India 1981 has promise. My issues won’t be addressed before the end of the campaign, but games often evolve after crowdfunding campaigns and it wouldn’t surprise me if that happened here. I love that this game is out there, because we need more faces in the hobby bringing their ideas to the table.

Tycoon: India 1981 isn’t “there” yet for me, but I will continue to follow this one closely. I’m hoping that a few changes help it cross the finish line.

Add Comment