If you haven’t figured out by now, abstract strategy is a style near and dear to my heart. My first “real” games—games that didn’t consist of simply rolling dice and advancing pawns along colored tracks—were abstract strategy. Quarto was the first game that truly captivated me, mind and soul. Abalone and Pente broadened my horizons and my skills. And now, some 20+ years later, I find myself constantly charmed and enchanted when a publisher puts out a good abstract game.

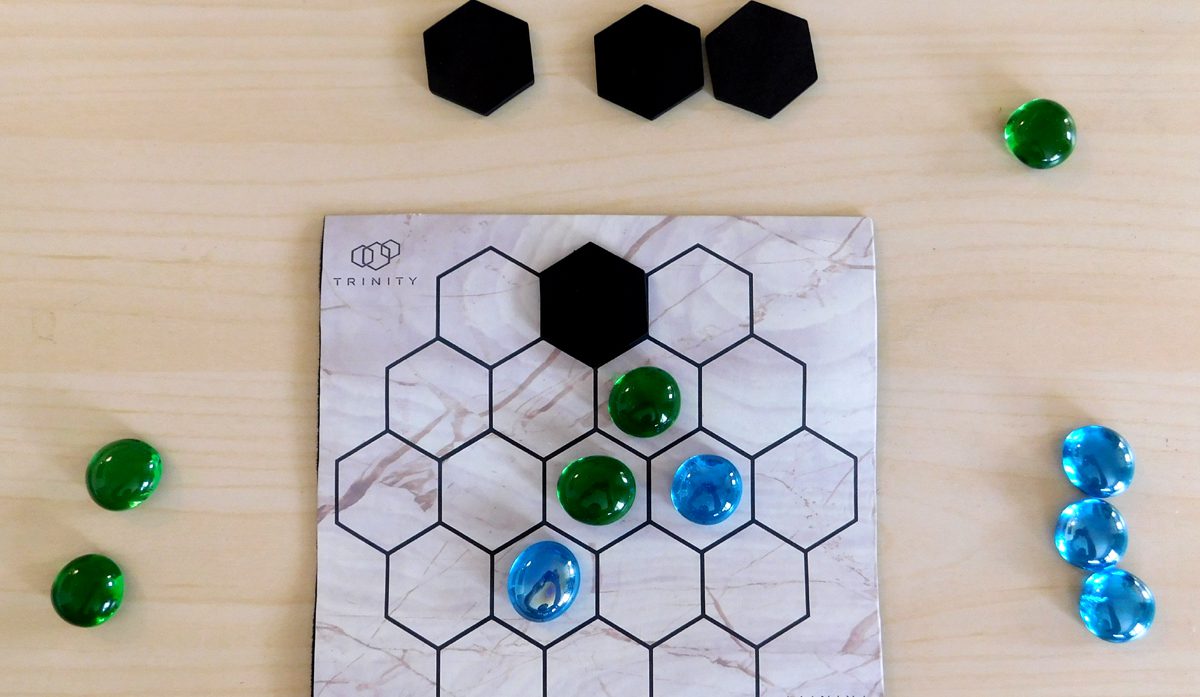

Trinity is a new title from Polaris Games and is the epitome of “abstract strategy.” A scant handful of pieces each (five per player, to be exact) and several black hex tokens along with a small, roll-up gameboard all inside a zippered case that’s little-larger than one that might hold your sunglasses. And that’s everything, which is why you won’t find too many pictures accompanying this piece.

What’s here is neither cheap nor glamorous: it’s perfectly utilitarian. This, in my childhood, would have been entirely adequate. In today’s climate of glitz, and glamor, and over-production (which, I would like to add, is not necessarily a bad thing) it may, unfortunately, be a stumbling block to reaching its full potential. Much like the excellent Push Fight, this is a good game in an adequate package, and in 2019 I fear that might not be enough (but more on that later).

Why do I care, you ask? Because like the aforementioned game, Trinity is pretty good and, I fear, destined to be overlooked.

So, now that I have thoroughly and completely buried the lead, let’s talk about how Trinity plays. Like Pente, Checkers, Go, and many others, Trinity is a game about maneuvering your positions and manipulating your position to surround and capture opposing pieces. Unlike those three others, though, Trinity is played on a confoundingly-small hex-tiled board, which leads to a constant hemmed-in feeling and introduces a healthy dollop of stress from the very start.

The board begins empty and, on their turn, each player has the choice of adding one of their pieces to the board (if they have any remaining, that is), moving one of their pieces by 1 space, or (if they have any) placing a black hex somewhere around the edge of the board. Pieces are considered “trapped” if they cannot freely make a move (although there’s a provision for being pinned by one or some of your own pieces). And, since you can’t move through a narrow channel when the two hexes that pinch it are occupied by opposing pieces, being “trapped” isn’t just a possibility, it’s an inevitability.

Trinity doesn’t seem like a game that will have much strategy when you begin, especially as you try to work out the nuances and finer points of how pieces can and can’t move and what constitutes a capture. It’s a slow-burn, for an abstract strategy game, that requires somewhat more double-checking of a manual that doesn’t provide much illumination. And that’s not all on the manual. At times, you’ll find yourself searching for rules you are sure must exist because the game seems almost too straightforward. It isn’t, though, and that feeling will pass with a few plays. At a brisk 5-15 minute playing time, that won’t take too long, either.

You find, however, that much like a wrestling match, it’s the subtle movements and strategies that can shift the balance of the game and cause a close match to suddenly be blown wide open. Your pieces circle your opponent’s in a mirrored dance fraught with tension and peril. You advance a piece, they retreat; they attempt to flank and you pivot back to counter. One misstep quickly becomes a pin and capture but, rather than leading to quick demise, the game gives a tool to compensate the injured player: a black hex piece.

Each time a player loses one of their pieces, they receive a hex, and those hexes can be placed as a turn around the edge of the board, essentially closing the walls (these hexes cannot be moved onto and effectively change and erode the board shape) and, in some cases, springing a trap on an unsuspecting opponent. Because once you have a hex in your hand you have the ability to suddenly take away a potential escape route, causing a previously-safe enemy piece to suddenly find itself pinned, with no legal moves. These hexes seem like a painfully insufficient recompense for your own lost piece, at first, but you quickly realize that they can be just as powerful as your fallen soldier.

I call it a soldier despite the fact that it is simply a glass aquarium bead, green or blue, with no other markings. And therein lies the issue. As the landscape of the gaming industry has expanded, the abstract strategy genre has been pressed to the margins. The classics endure, but to make a splash in the newer, shinier, more crowded marketplace a game has to stand out. Today, it seems, a game needs a coat of paint or two in the form of aesthetics and theme, even if it’s lightly applied, to capture the imagination of the crowd.

Is this fair? Hardly. My favorite abstract game of all time is Quarto which I strongly suspect would struggle to find a footing if presented the same way in today’s market. But right or wrong, it’s a fact of the gaming scene as its stands today and one publishers need to take into account as they bring their games to market. Trinity, for all its merit and quality, may struggle to find a crowd amidst lesser games with more appealing, imaginative trappings.

Why, you ask again, am I bringing this up? Because Trinity is a lot of fun. It’s a smart little game that plays quickly and can be brought just about anywhere. It’s a game you’d regret missing, yet one you more-than-likely would have missed. So I’m mentioned all of this to say this: don’t let this game’s low profile keep it off your radar. Go, look at it, watch some videos, and consider backing it. If you love the very popular Onitama or Hive, then you’ll like this one too.

Add Comment