Even though Stan Lee called the Scarlet Pimpernel the first superhero he admired, I doubt you’ll be seeing Baroness Orczy’s celebutante in the MCU anytime soon. Published in the early 20th century, the tales of the Scarlet Pimpernel follow England’s deceptively capable man of mystery into the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution as he rescues aristocrats from the guillotine. He had all the honor of Steve Rogers and all the money of Tony Stark.

Baroness Orczy penned nearly a dozen novels about Sir Percy Blakeney—the man behind the countless costumes—and his infamous League. The stories of daring rescue are pulse-pounding page turners. Will the Scarlet Pimpernel keep his word? Will he arrive in time? Will he escape the deft clutches of Chauvelin once again? Every punchy chapter ends with a question that begs just a few more minutes by the fireside.

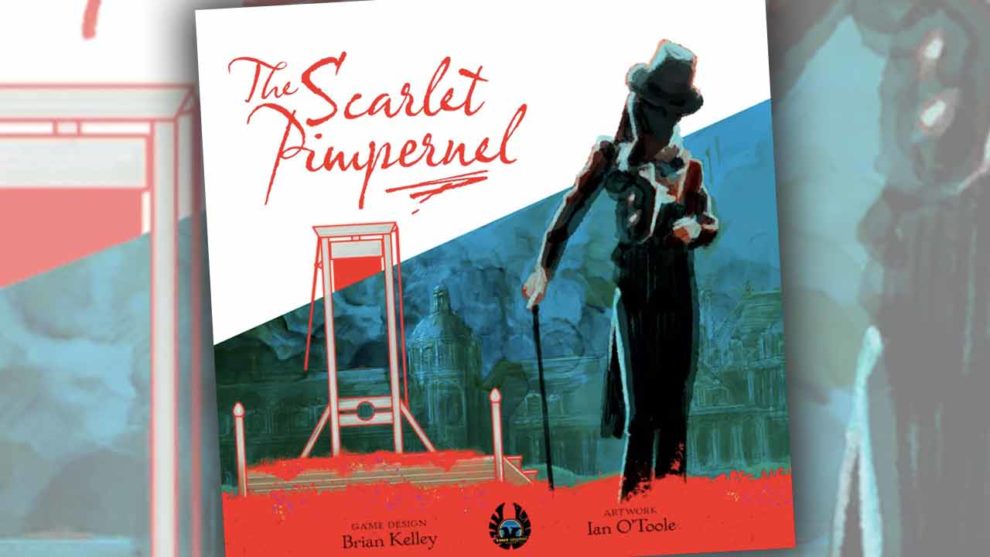

I invite you to fast-forward a century from the novels to explore Brian Kelley’s 2019 tabletop design, The Scarlet Pimpernel, published by Eagle-Gryphon Games. Players take up roles in the League of the Scarlet Pimpernel to help the titular hero through seven missions on both sides of the English Channel.This semi-cooperative game sets at odds the desire to see the hero succeed with the desire to become the most trusted advisor.

The Way of the Scarlet Pimpernel

The Scarlet Pimpernel takes place on a big, beautiful, six-fold board with big, beautiful components. The board is a map divided into four regions: England, France, Paris, and Vienna of the late 18th century, with various locations dotted about and connected by a network of roads.

The goals in each of the seven rounds are: 1) prepare a route for the Scarlet Pimpernel from his current location to the destination, 2) prepare the destination by engaging the actions on the location’s card, and 3) gather the required resources and connections for the Mission.

Players each receive an identity from the League and a set of marker cubes to place repeatedly throughout the game. At the outset, a player turn consists of one of three actions: Move to an adjacent region, Place a cube on an eligible space in your character’s current region, or take a Building action.

Cubes are the lifeblood of The Scarlet Pimpernel. They are placed and, hopefully, scored in each round, after which they return to their owner for use in the next Mission. Should a cube not score, it remains on the board until reclaimed via a pickup action or employed in a later Mission.

Some will be placed along the roads in the hope of being selected as part of the path the Pimpernel will travel. Some will be placed on location cards, triggering a variety of actions and bonuses. Some will be placed on Buildings used to prepare various resources needed by the Scarlet Pimpernel: disguises, forged documents, wagons, and horses. Some will serve to influence the political scene, glad-handing the individuals who can ensure missional success. Finally, some will provide rest—a deferred action that can be reclaimed during a later turn.

Many of these cubes are distributed in six specific areas on the board which function as area majority battles. Each area provides a Special Favor action to the current majority holder. These Favors are double actions that can be used in place of the game’s base actions. Throughout the seven rounds, these Favors change hands every time the majority shifts, creating a healthy and active power struggle.

There are five Mission spaces in the Northeast corner of the board. By marking these spaces, players are essentially laying claim to the success of one aspect of the Mission: that the resources will be acquired, the political allies schmoozed, the route secured, and the location prepared before the Scarlet Pimpernel moves. The fifth spot is a claim to the first player token, a note from the mysterious hero himself.

For each aspect that is successful, the Leader who marks each Mission space receives a point and selects the cubes to score for that round from the resource and politics areas, the route, and the destination card.

When an aspect of the Mission is unsuccessful, the cubes on the map score, but the Leader cube is worthless. If the Chauvelin variant is in play (which, I believe, it always should be), failed Mission spaces advance the French hunter towards the Scarlet Pimpernel. Should he ever catch the hero, the next Mission begins from a Parisian prison with the target location being as far away as physically possible. Failure begets failure. Without Chauvelin, there is almost no reason to care about failure other than simply withholding single points from another player.

There is a balance on the map between speculation and security. Placing the shortest route is easy, but if there’s time the route Leader might sneak in a stop through a nearby location to divert points and weaken others’ future cube supplies. Placing cubes in resources can secure Favors, but placing too many might leave a few additional cubes stranded when you could use them elsewhere. Assuming the lead on the destination card might not pay off, but it guarantees the right to select the next destination. It is important to get the right markers in the right places at the right time to move up the scoreboard.

The seventh and final Mission stretches into Vienna with a super-stacked set of required resources and political alliances to match the inconvenience of the location. Whether with success or failure, the game ends after Vienna and the final tally unveils the winner.

The Triumph of the Scarlet Pimpernel

In fiction, the Scarlet Pimpernel never fails. Sword fights and chases, near-captures and clean getaways, Lord Blakeney gets his target across the English Channel. Chauvelin is always biting at his heels, but it is the classic tale of feigned worry over whether he will succeed with the real excitement being how he will prevail.

On the table, the Scarlet Pimpernel might fail if it serves a player to botch the Mission. This is perhaps the greatest thematic disconnect, but one that is necessary if the game is to be any fun. Narratively, the failures must be viewed as mistakes that caused drama and near catastrophe, even though they often occur through flagrant negligence.

In fiction, Chauvelin will use everything he knows and all his cunning to manipulate the League into revealing the Scarlet Pimpernel’s identity and secrets. On the table, he is reduced to a slow walker that can be held easily at arm’s length. I feel this is the greatest missed opportunity in the game. I wish there was a mechanic where Chauvelin threatened each player privately via a card of sorts, forcing a hidden decision of whether to stand up to him (and suffer for it) or bow down to him (and suffer differently for it). If half or more give in, Chauvelin moves in hot pursuit. I feel this would make The Scarlet Pimpernel beautifully immersive without succumbing to a full traitor mechanic.

As it stands, however, this particular Eagle-Gryphon title is a pretty subdued adventure. Don’t misread me: I really do like The Scarlet Pimpernel. It’s missing a layer of excitement, but there is a fun little set of head games on this map. It stays in the collection.

Depending on the player count, different aspects assume a different level of importance. At the full six-player count, the route Leader is a crucial position. With many contenders vying for a particular path, the Leader will often play the spoiler, stranding various markers around France and potentially affecting future rounds. For two and three players, choosing the next location is hyper-critical because the game moves faster and it’s far more plausible to plan ahead—provided you have a clue how to do so! I celebrate that variety.

The key becomes knowing when to jump in on certain placements based on the rhythms of the group. It’s important to gain and steal away Buildings to maintain presence in the area control fights, but sometimes reclaiming one may involve traveling to a region outside the current action. Is it worth the time, energy, and resources? Placing cubes in Rest always feels like a downer, but yanking one of them out to unexpectedly close off the last Mission space and cut short another player’s bid for a more lucrative route is downright satisfying.

The game could potentially be one Mission shorter. Seven is a lot, especially at the lower player count. But if players keep their eyes to the map, the game is quite snappy. In the four player game, each player has fifteen possible cubes in every round—sixty total. But a round of turns could take less than 30 seconds if folks are on the ball. Still, games can stretch past 90 minutes.

Regardless of the length, watching eyes turn toward Vienna and the final Mission is quite entertaining. In a three or four-player game, one player could (should?) conceivably abandon the sixth Mission and start laying groundwork for the seventh before anyone else can get a cube to the ground. Rude? Perhaps. Shrewd? You bet, and fun, too!

Semi-cooperative games are a mixed bag. There’s something strange about helping while simultaneously trying to stifle your peers, but I enjoy the awkwardness of it all. The Scarlet Pimpernel is designed to be a game of inches. I’ve played with every count except five players, and no game has boasted even ten points between first and last place. The lower counts often end within a point or two. In one of our four-player outings I thought I had the math worked out and I ended the game early—much to the chagrin of the entire table—only to find out that I had miscalculated by three points, which set me in third. The compact spread is the effect of playing both sides of the semi-coop fence.

Eagle-Gryphon games come with a price tag warning. The component quality is fantastic from the meeples to the Special Favor tiles to the beautiful and oversized map, but that keeps the retail asking price high. Ian O’Toole’s artwork is characteristically stunning. For a game that is essentially placing cubes on a map, he brought a lot of personality to the production that injects life.

For fans of the novels, I would recommend The Scarlet Pimpernel. For fans of semi-cooperative play, I would recommend it as well. It’s a fun little route-building battle of wits, but it’s the Tokaido of adventure games. If you’re looking to set your hair on fire with a screaming barn-burner on the table, this tree is not the target of your barking—it’s pretty laid back.

If ever something like my Chauvelin variant sees the light of day, I could see this one being among my favorites for its combination of charm, table presence, and conversational decision-making. As it is, I believe we’ll play it from time to time without hesitation, just to see if we can save a few necks and have a good time about it.

Add Comment