Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

In the Kennerspiel des Jahres award-winning The Quacks of Quedlinburg, you aren’t speaking with the witch doctor about your love problems, rather you actually are the quack doctor healing the citizens’ ailments during Quedlinburg’s annual 9-day bazaar.

Each player acts as a quacky doctor and showcases their skills by brewing potions using ingredients from their personal bag of tricks. The better the potion, the more money a player receives to buy fancy, more advanced ingredients for their bag. If a player is lucky, they also earn victory points for their brews; but if potion brewing was as simple as this then everyone would be doing it. It takes skill to know when to stop adding ingredients to your pot since every player’s bag has a number of special ingredients which will make their brew pot explode if too many are added.

The Quacks of Quedlinburg is a bag-building game (like Altiplano or Automobiles) with a push-your-luck element. If you’re unfamiliar with the term “bag-building”, think of it as a deck-building game with a bag instead of cards and increased randomization. Each player starts the game with a bag of tokens (in Quacks, these represent ingredients) that is identical to the other players. However, as the game progresses, players will buy their own ingredients and the distribution in each player’s bag will change.

The push-your-luck element comes out during the gameplay each round. Players independently draw ingredients from their bag until they decide (or are forced) to stop. If a player is greedy and unlucky their pot might explode, forcing them to stop drawing ingredients and not earning them all the possible rewards. Levelheaded players who choose to stop just in time will earn both money and victory points… but will their cautious efforts be enough to win them the game?

The Three Phases of Brewing

The Quacks of Quedlinburg is played over 9 “turns”, but I prefer to think of them as rounds since everyone plays simultaneously and there are no actual player turns. Each round goes through 3 phases: Preparation (getting things ready for the next round), Potions (drawing ingredients from your bag to make your potions), and Evaluation (earning money and points for your potions and possibly acquiring new ingredients).

Preparation Phase

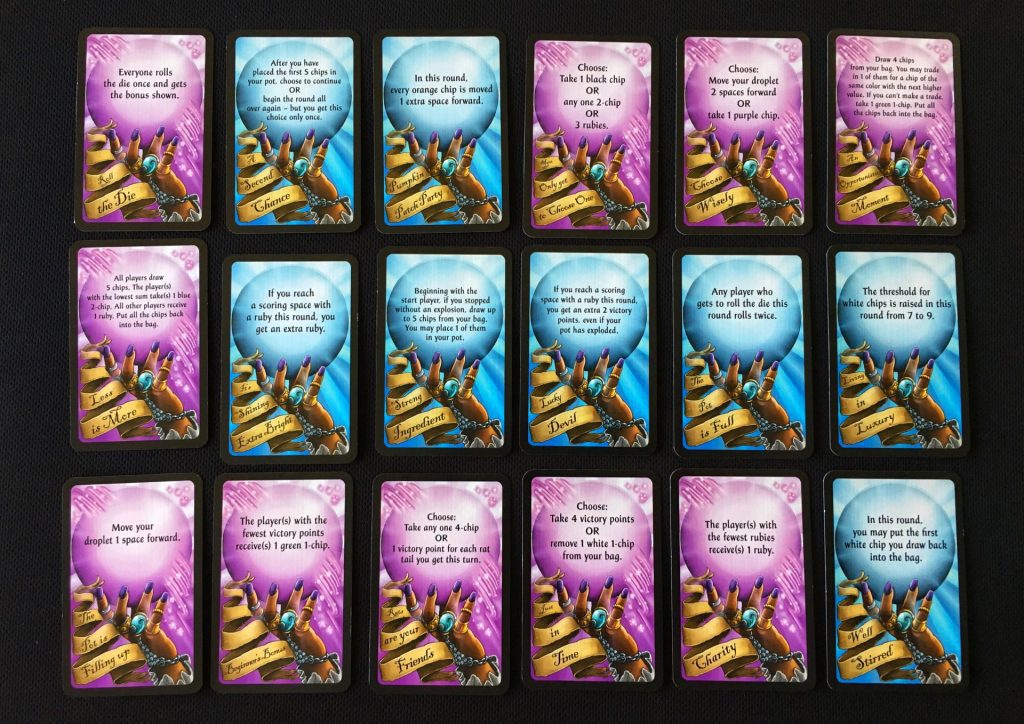

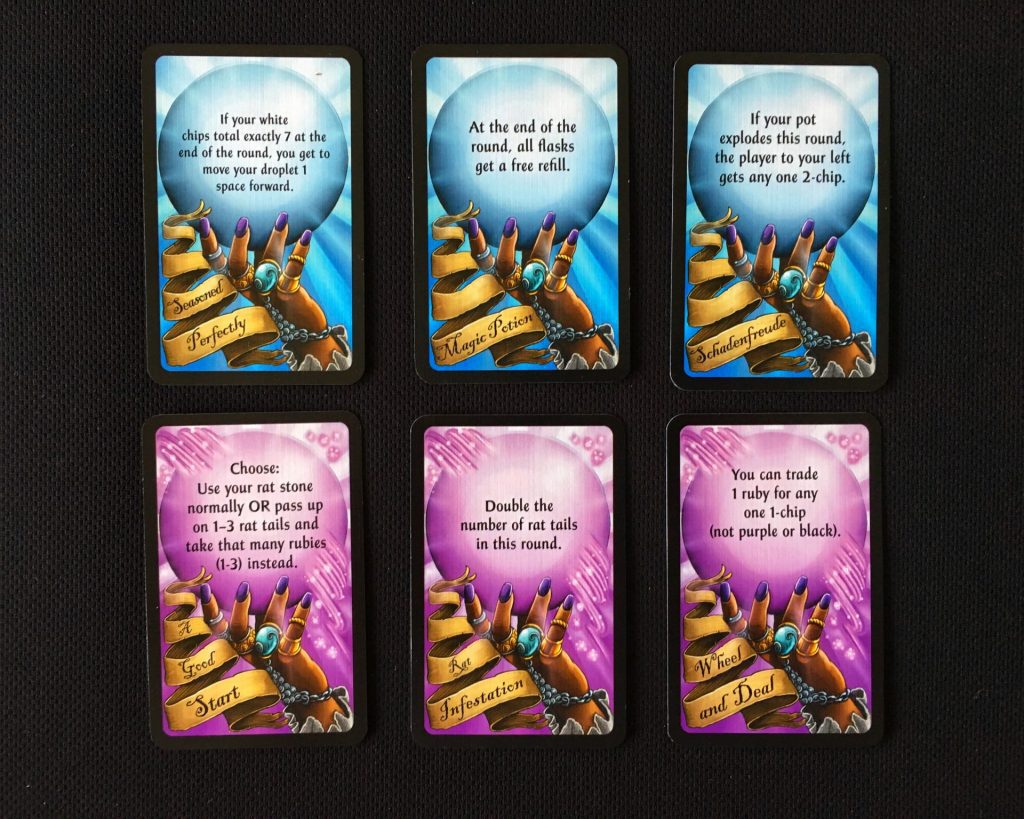

At the beginning of each round, a Fortune Teller card is drawn and its effects are applied to all players. Thematically these cards set the conditions for the brewing day ahead. In practice, these cards work as temporary events, adding some variance to make each round slightly different.

Starting in the second round, rats could make their way into your pots. This is, unexpectedly, great news because the rats fill up your pots without costing you a thing. Think of them as a cheap filler ingredient you’ll use to make that round’s brew a little more substantial. In gamespeak, the rats act as a catch-up mechanic; as players progress on the Scoring Track, they pass over rat tails. For each rat tail between you and the leading player, you move your rat token ahead that many spaces during this phase.

If the rats seem a little confusing right now, don’t fret. It will all make sense once you learn how the Potions phase works. What’s important to take away is that the rats are helpful and if you aren’t the leading player (and sometimes even when you are), you want the opportunity to add rats to your pot.

Potions Phase

During the Potions phase, players draw ingredient chips from their bags and add them to their pot (remember there are no player turns). This is the most thrilling part of The Quacks of Quedlinburg!

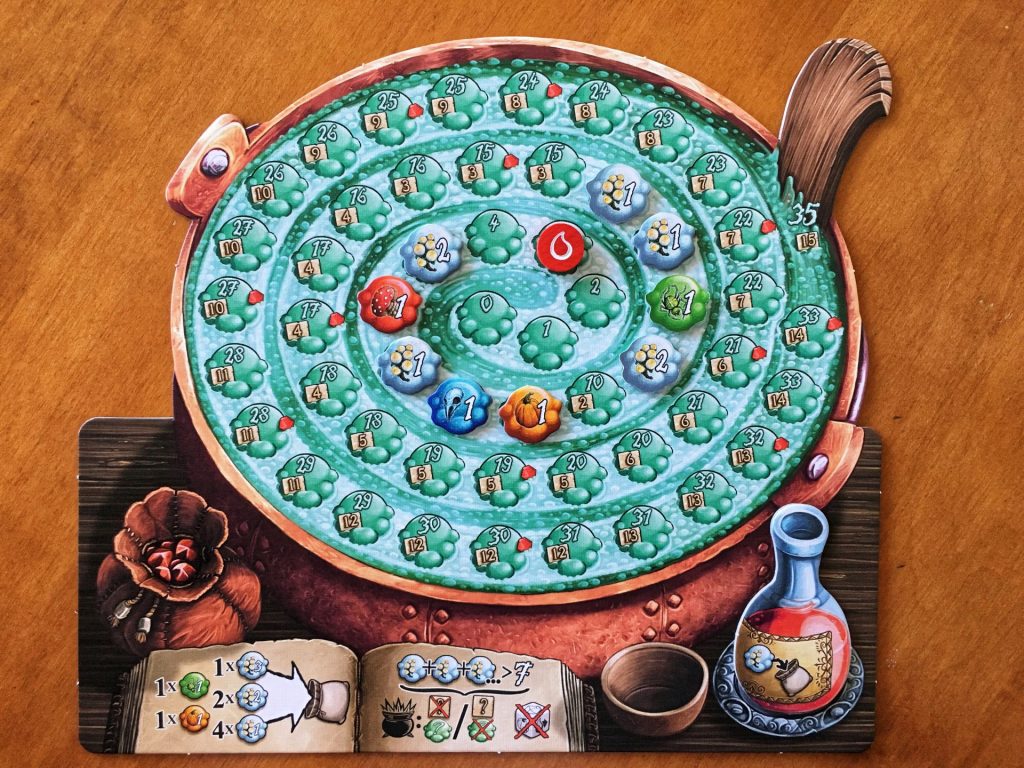

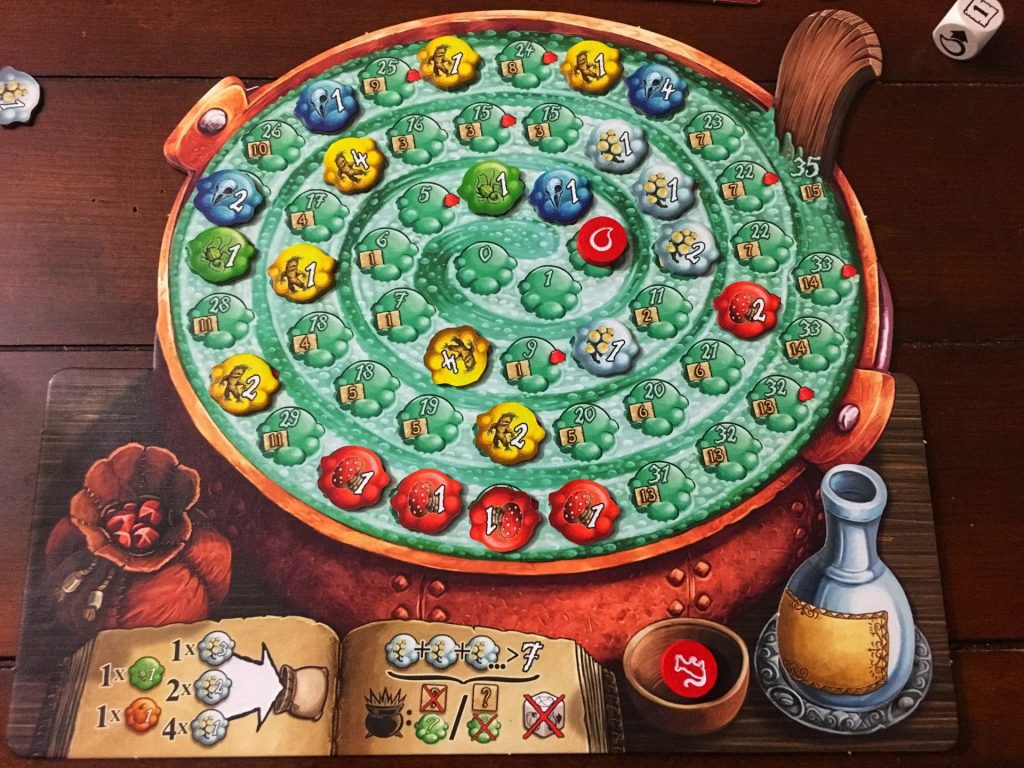

Each player starts with their droplet token on the 0 space of their pot; this droplet marks the starting point for your pending potion. While the droplet begins the game on 0, players will have opportunities to advance their droplet throughout the game, obtaining money and points more quickly (and with fewer ingredients).

As ingredients are drawn from the bag, they are placed in a player’s pot based on the number found on the chip: an ingredient with a 1 is placed 1 space after the droplet (or the rat), an ingredient with a 3 is placed 3 spaces after the droplet, and so on. Subsequently drawn ingredient chips are placed in the pot in the same way, always after the previously laid chip.

After each chip is drawn and placed, players have an important decision to make: will they draw another chip from their bag or stop? The most common reason a player might choose to stop is because they are afraid of their magnificent pot exploding.

Cherry Cherry Boom Boom – Potion Explosion

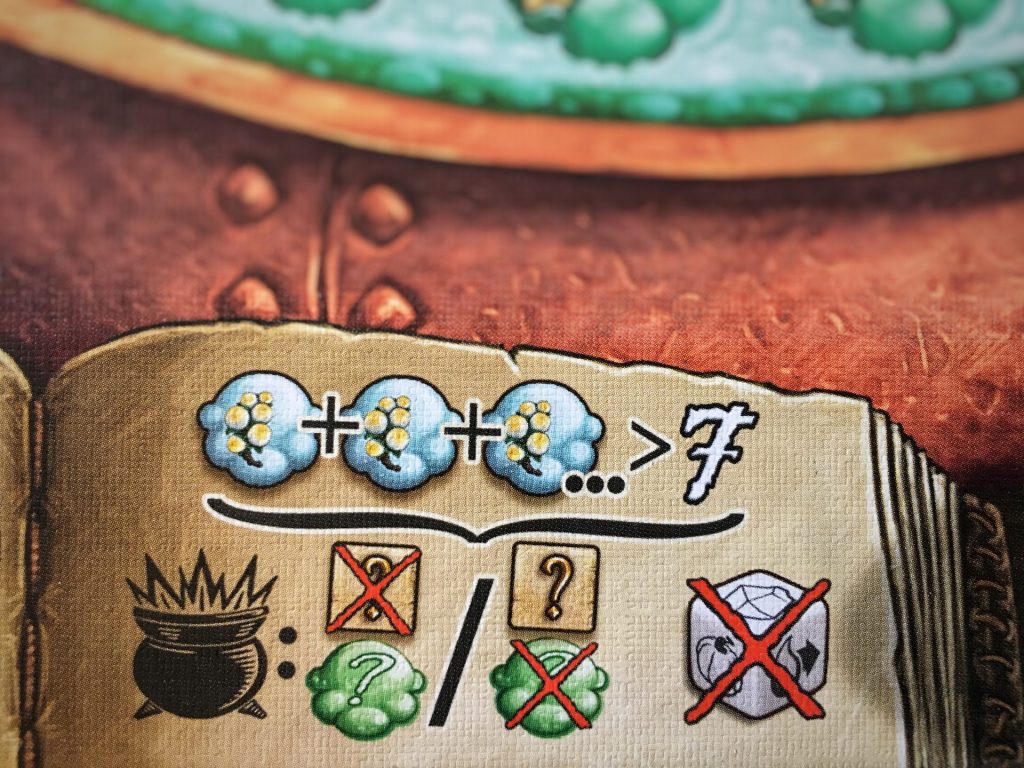

In The Quacks of Quedlinburg nothing really fantastic comes from your pot exploding, but fortunately there is only one way in which it can explode: if the sum of the white ingredient chips (the Cherry Bombs) drawn exceeds a value of 7.

When a player draws a white chip, they add it to their pot as they would any other ingredient. Then they sum the value of all the white chips in their pot and if it exceeds 7 they are forced to stop drawing chips and take care of their second-degree burns. Players with exploded pots will lose out on some benefits during the Evaluation phase.

Thankfully, as the quacky brewer that you are, you begin the Quedlinburg festival equipped with your flask. If you draw a white chip from your bag, you may use your flask to return that chip to your bag only if the drawn chip wouldn’t have caused your pot to explode. The flask is then turned over to its “empty” side and cannot be used again until it is refilled, usually during the Evaluation phase. Flasks can be especially useful later in the game when you have a bag full of ingredient chips and you pull your only 3-value white chip on the first draw… which happens more often than you would expect.

The Potions phase ends once all players have chosen to stop (or were forced to because of an exploding pot).

Evaluation Phase

Every Evaluation phase runs through the same six steps (found on the Scoring Track board).

Most of the steps in this phase are based on a player’s scoring space for that round. This is the space directly after the last chip placed in a player’s pot, whether that chip caused an explosion or not.

The first step of the Evaluation phase (Bonus Die) is only for players whose pots didn’t explode. These players check to see who amongst them reached the highest scoring space. Then, the player (or players) who reached the highest space may roll the bonus die to gain a reward.

The second step of the Evaluation phase is the Chip Actions. Depending on the sets of ingredients used, the green, black, and purple chips might have actions or benefits that are gained at this time.

Players receive rewards in the next three steps (Rubies, Victory Points, and Buy Chips) based on their scoring space. During the Rubies step, if your scoring space depicts a ruby then you get a ruby, even if your pot exploded.

Now everyone gains victory points — the number of points earned is depicted on the scoring space’s parchment. However, if your pot exploded you must face the consequences and decide which reward you would like to gain from your scoring space: victory points or money to buy chips in the next step. If your pot didn’t explode, you earn both points and money since you were such a (ganz schön) clever potion brewer.

Next players earn money according to the larger number on their scoring space. Money is used to buy 1 or 2 ingredient chips, but it cannot be used to buy 2 chips of the same colour. The cost of each chip varies depending on the type of ingredient and how strong that ingredient is.

Once players have finished purchasing their ingredients, all drawn chips in the pot and newly purchased chips are returned to their bags.

Players then move onto the last step. Here a player may spend rubies to fill up their flask, move their droplet forward, or do both if they can afford it. Finally the round indicator moves forward on its track. At the start of round 2 and 3, the yellow and purple ingredients are added to the game and at the beginning of round 6, each player adds a white 1-chip to their bag. No one said brewing potions would be painless!

Biggest Quack of Quedlinburg – End of Game

The ninth and final round works like the eight that came before it, except that every 5 coins and every 2 rubies earn players 1 point each during the Evaluation phase (since it’s no longer helpful to buy new ingredients, move your droplet, or fill your flask). There is also a rule for this final round which suggests players draw ingredients out simultaneously, one at a time, to prevent anyone from having an advantage by seeing what their opponents drew before they choose to continue or stop. In my first game we played this way, but I found it slowed the pace and took away from the excitement such that I’ve never played this way again.

The quack with the most points wins, so to speak.

The Almanac of Ingredients

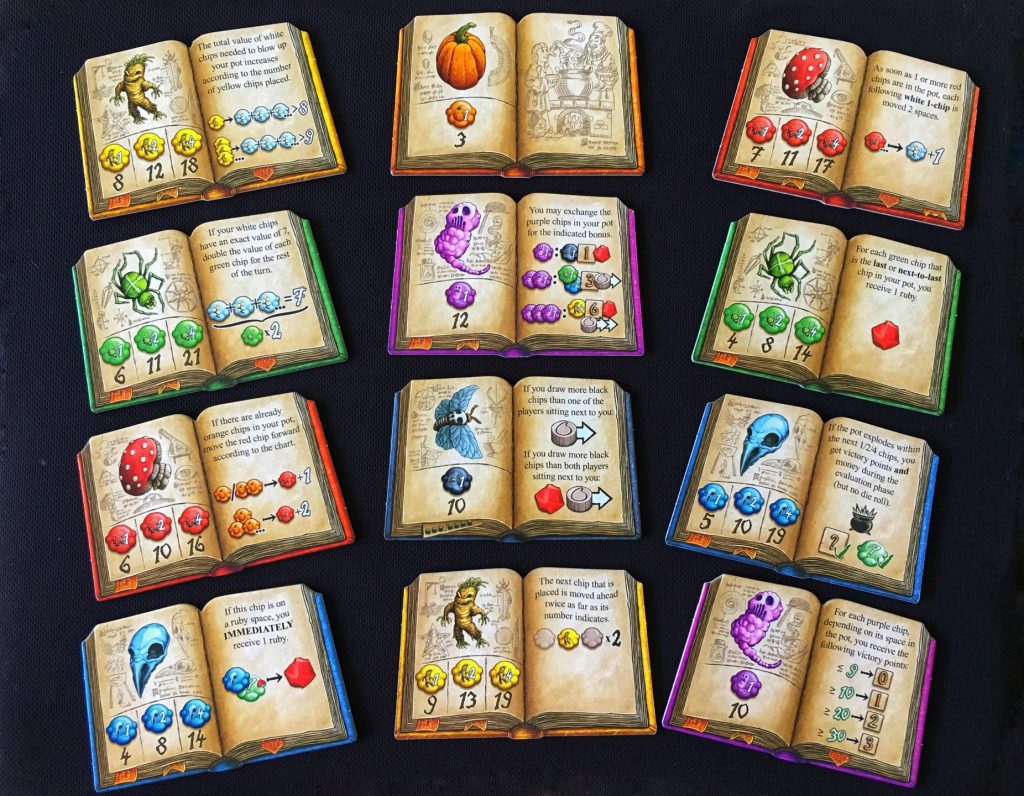

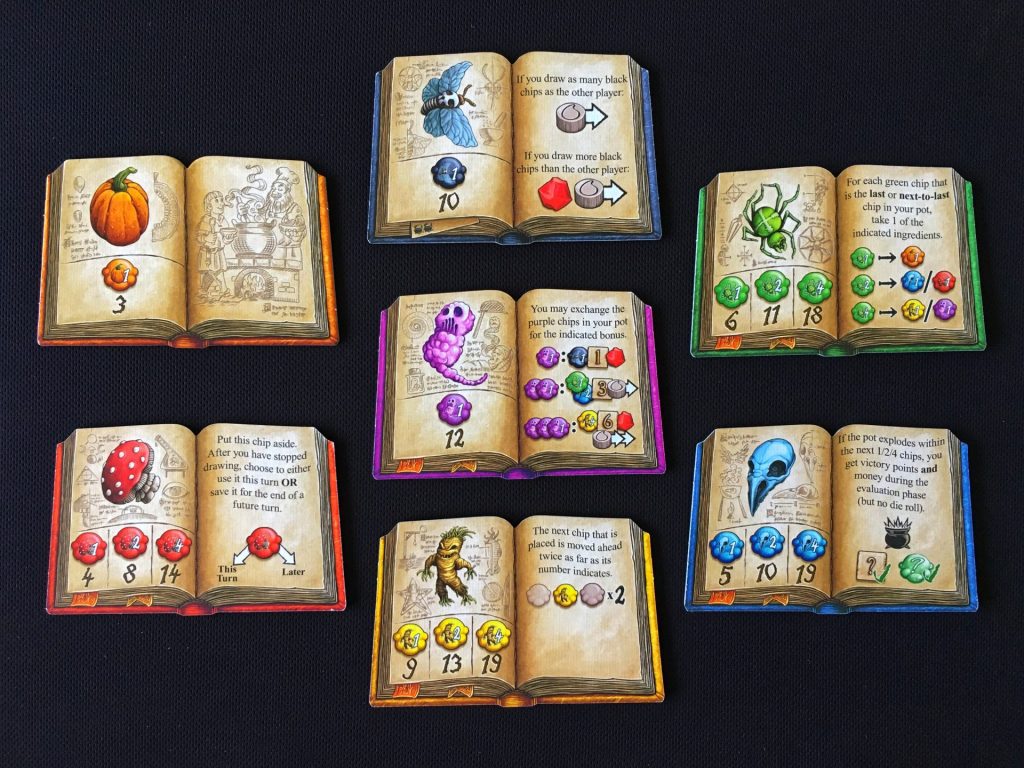

In The Quacks of Quedlinburg players might have eight different kinds of ingredients in their bags, many of which have a bonus ability associated with them.

The first ingredient, the Cherry Bombs, cannot be bought; they make up most of the ingredients in a player’s starting bag and are the only ones which cause a pot explode. In general, the more of them you have added to your pot, the closer you are to singeing off your eyebrows.

The next ingredient is the Pumpkin. Pumpkins are basic. They are inexpensive, not super helpful, and don’t have a special ability when they are drawn from your bag. However, adding a chip or two of this ingredient will pumpkin spice your potion right up.

The black African Death’s Head Hawkmoth adds some player interaction to The Quacks of Quedlinburg. Depending on the number of players in the game, players gain certain rewards for having more of these chips in their pot than their opponents.

While these three ingredients remain the same from game-to-game, the next five ingredients have varying abilities which are divided into four different sets. Even though an ingredient’s bonus ability changes with each set, they do have some inherent qualities.

Ghost’s Breath, the purple chips, are resolved during the Evaluation phase and they either give a player benefits based on the number of them drawn or where they are placed in a pot.

The green Garden Spider chips usually give a player a bonus during the Evaluation phase if it was the last (or next to last) chip placed. However, in one set, the Garden Spider’s value will double if there are enough white Cherry Bombs in a player’s pot.

The Toadstool (red) ingredient chips also sometimes work alongside the Cherry Bombs by increasing their value or by moving a chip further forward (this is even true for the plain Pumpkin in set 1).

The blue Crow Skull chips are one of my favourite ingredients, no matter the set used. These ingredients are very particular: often you only gain the benefit from a Crow Skull if you happen to draw it at just the right time or place it on just the right space in your pot. I find it is the most opportunistic ingredient in The Quacks of Quedlinburg and I love the roller coaster-like journey of emotions I go on every round as I wish for the Skulls to be drawn from my bag.

The yellow Mandrake is my other favourite ingredient. They are the most lucrative, in my opinion, because all the little Mandrakes want to do is help you be the best you can be and reach further ahead in your pot. Sometimes their value might double and sometimes they increase your Cherry Bomb explosion threshold, for example. They are wonderful, darn cute, and you don’t need to worry about wearing earmuffs each time you pull them from your bag.

Final Thoughts

Often I feel like Vincent Adultman: just a child wandering through adult life in a trench coat equipped with a mannequin arm and a broom as my hands. I feel this way because I love to play; it makes me happy. But it takes a special kind of play to take me back to the joyful times from my childhood when I would buy a Mystery Bag at the corner store. I would feel my excitement mount, beginning as I searched through the options for the perfect bag and continuing until I tore it open on the store’s curb (much too excited to wait until I got home). It was usually filled with chalky candy and plastic toys that didn’t work, but that didn’t matter because the exhilaration was worth my $2 … Every. Time.

The Quacks of Quedlinburg stirs up the same childlike joy in me and I am filled with glee each game as my fingers carefully hunt through my bag for the perfect ingredient chip, hoping to pull it out. Quacks also sparks a very adult kind of thrill: that of gambling and greed. It is really difficult to stop pulling chips from your bag when you are riding such a high from all the good luck you had up to that point. My constant “I only have one chip that could make my pot explode, yet a bag full of good ingredients” or “I’ll stop after the next chip” usually result in my pot exploding. But it’s soo exciting when it doesn’t — and it’s these few moments that make all the explosions and loss of points and money oh so worth it.

For a game that relies a lot on luck, The Quacks of Quedlinburg feels strangely balanced. Scores tend to max out in the high 50s (although I broke 60 once… that was a good day) and are usually not below 40. The rat catch-up mechanic works very well to help mitigate a runaway leader. I think this is probably why I’ve never seen someone leaving a game feeling salty. Whether you’ve drawn well or poorly, pushed your luck too far or not far enough, no player is ever left too far behind.

None of this is to say that the game isn’t without its flaws. For one, the rulebook that details each set of ingredients isn’t always the most clear. A quick visit to BoardGameGeek usually clarifies any questions, but I feel like I shouldn’t have to take this extra step.

My other complaint is the Fortune Teller cards. In theory, I like their purpose and how they often work well. However, these cards are shuffled and drawn randomly so sometimes the effect just doesn’t work for the beginning or end of the game.

It can be disheartening when you are ready and excited to jump into the game, then the first card is revealed and it isn’t something that could possibly be executed. The easiest fix is to decide as a group to draw another card, but this feels like a bit of a waste. I would have liked to see some of these cards consolidated with text saying “in rounds 1 to 8, resolve this effect and in round 9, resolve this other effect”. In the picture above, for example, the Magic Potion and Rat Infestation cards could be combined so that in rounds 1 to 8 flasks get a free refill then in round 9, the number of rat tails is doubled.

No game is perfect though and the minor complaints I have about The Quacks of Quedlinburg will in no way stop me from playing the game. It is silly, it is exciting, and it is F-U-N fun. In fact I dare you to play The Quacks of Quedlinburg and not enjoy it. That is just how confident I am.

How does the rat work. Is it only used for 1 turn and then removed?

The rat isn’t removed from the game once it’s used, but it will “reset” (taken out of your potion) at the end of every round.

At the beginning of each round, you count to see how many rat tails there are between you and the leading player. You then move your rat token ahead that many spaces. If there are 2 rat tails between you and the first (leading) player, for example, you move your rat token 2 spaces ahead. At the end of that round, the rat token comes off your board (but could still be used in future rounds).

The next round, do the same again and count the rat tails. Let’s say there are now 3 tails between you and the first player. You would then place your rat token 3 spaces ahead for that round.

The rat tails aren’t cumulative. So let’s say in round three you had a rat 2 spaces ahead and then in round four, you had a rat 3 spaces ahead. Your token would *not* be 5 spaces ahead; it would only be 3 because the rat token resets/comes off your board at the end of every round.

Hope that makes sense : )

Thank you. We were playing the rat could only be used in oneround only per the entire game.