Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

“The purpose of our lives is to be happy.” The Dalai Lama.

Last week I married a lovely man called Jimmy. We raised a family, cultivated bonsai trees, built a swimming pool and eventually died in each other’s arms at the age of 70.

Was I happy over the course of my life?

Moderately.

Was the real me playing the board game The Pursuit of Happiness happy over the course of an hour?

Yes… mostly. Let’s talk about The Pursuit of Happiness.

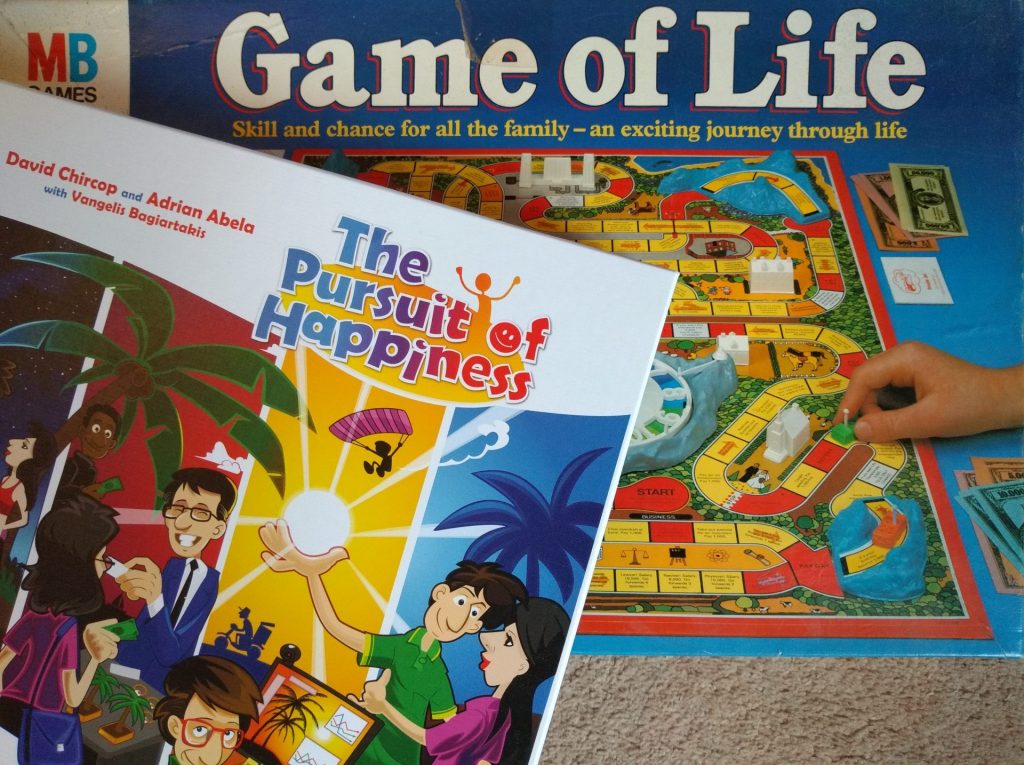

Designed by David Chircop, Adrian Abela and Vangelis Bagiartakis, The Pursuit of Happiness was originally published in 2015 by Artipia Games. Since then three Kickstarter campaigns have successfully raised funds for a reprint and two large expansions, with various promo-pack expansions available as well. Clearly there’s a decent chunk of people who like this game, so what’s it all about?

“Why are we here, what’s life all about?” Monty Python.

The goal of The Pursuit of Happiness is to gain the most Long-Term Happiness points. Long-Term Happiness points are achieved by collecting and completing the requirements of cards, which include developing relationships, climbing the corporate ladder, learning new skills and even collecting board games. Doing any of these activities takes time – you have 6 hourglass markers per decade of your life (round of the game) and spend most of The Pursuit of Happiness placing them on action spaces either on the main board (largely to claim cards) or on cards that you’ve previously collected to exchange resources for rewards. If you’re familiar with the board game hobby you may recognise this process as ‘worker placement’ but it’s generously tweaked from the stereotypical art form found in games like Agricola or Lords of Waterdeep.

At the end of each decade (once everyone has placed their hourglass markers) the current round is over. As players enter the next decade of their lives they pay upkeep costs for any items, jobs or relationships they have and gain resulting benefits. That mid-life crisis motorcycle from your forties needs maintenance in your fifties but still brings you a measure of joy as a result.

With old age comes stress and ill health until all too soon the decade arrives when you aren’t well enough to continue. That’s your life lived, your chips cast, your die rolled, your game literally over. Once everyone’s metaphorical and actual hourglasses have run out the game ends. You’ll get some final Long-Term Happiness points by converting any remaining currencies and from achieving any of the random Life Goals revealed at the start of the game. The bulk of your points, however, are going to come from what you got up to in life as opposed to what you leave behind.

There’s a lot I’ve skipped over but that’s the gist of The Pursuit of Happiness. Think of it as a hobby version of The Game of Life, except that what players are trying to end the game with is the satisfaction of a life well lived rather than cold, hard cash.

But is it any good?

The short answer is that it’s a great game despite itself. I’ve found The Pursuit of Happiness consistently interesting, satisfying and fun, but there are also some issues that range from bafflingly frustrating to genuinely irritating. Happily, the game’s strengths easily obscure these issues after your first game or two but they never completely go away and that first game could be a bit bumpy.

God and the Devil are both in the details, however, so let’s dive into the longer answer which will hopefully help you discover whether it will be a great game for you. Let’s start with the bad and then we’ll get on to why, for me, they shouldn’t put you off.

“If you want the rainbow, you gotta put up with the rain.” Dolly Parton.

Some of the production choices in The Pursuit of Happiness seem to be actively experimenting with self-sabotage. I’m no font-Führer but the illegibility and the tiny second digit for amounts of money fill me with rage in the way that Comic Sans doesn’t.

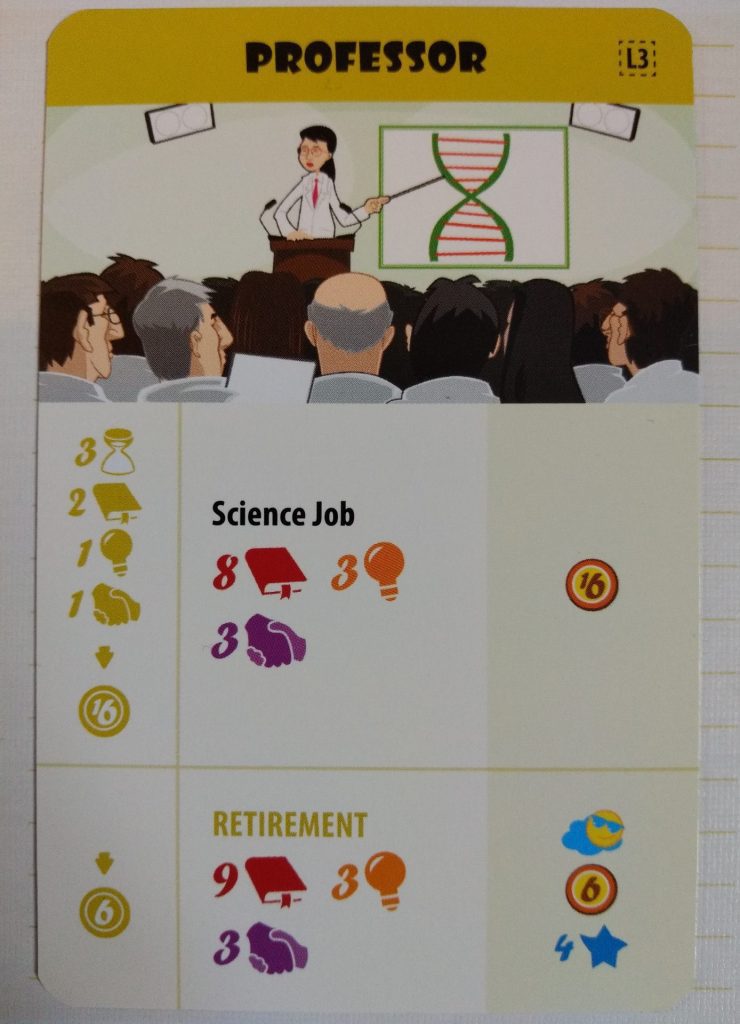

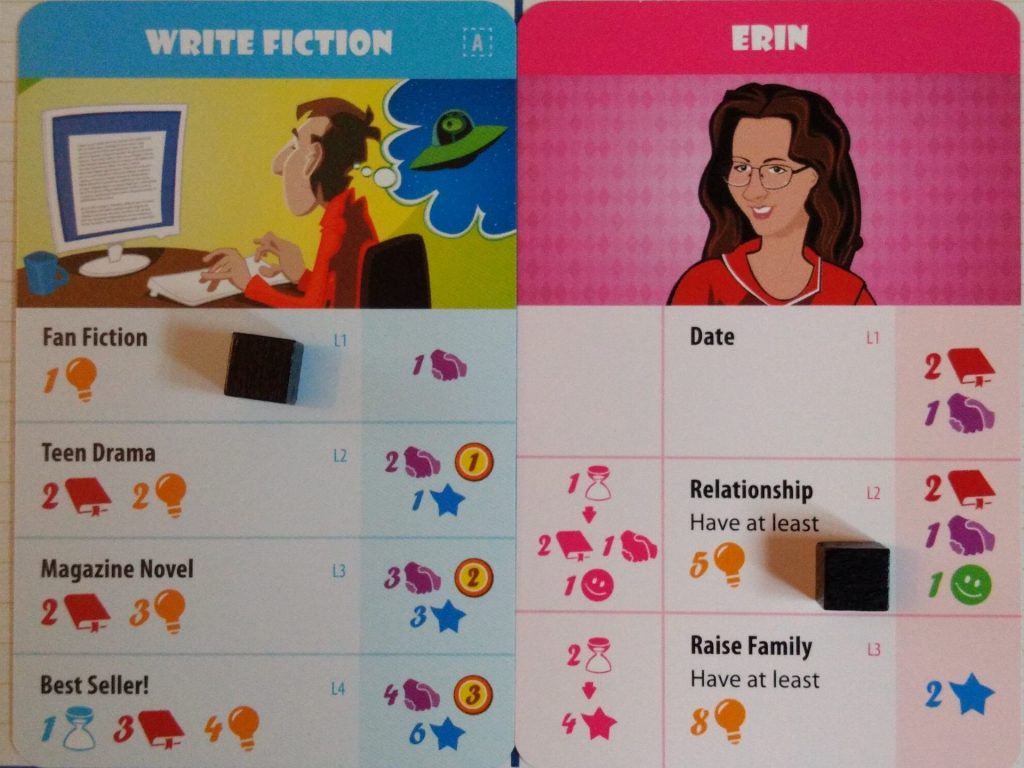

The card layout is curious too. Cards convey lots of information, especially those with initial and ongoing costs/rewards. Convention in the Western world is that communication reads from left to right. So why put the ways you’ll interact with the cards in the opposite order?

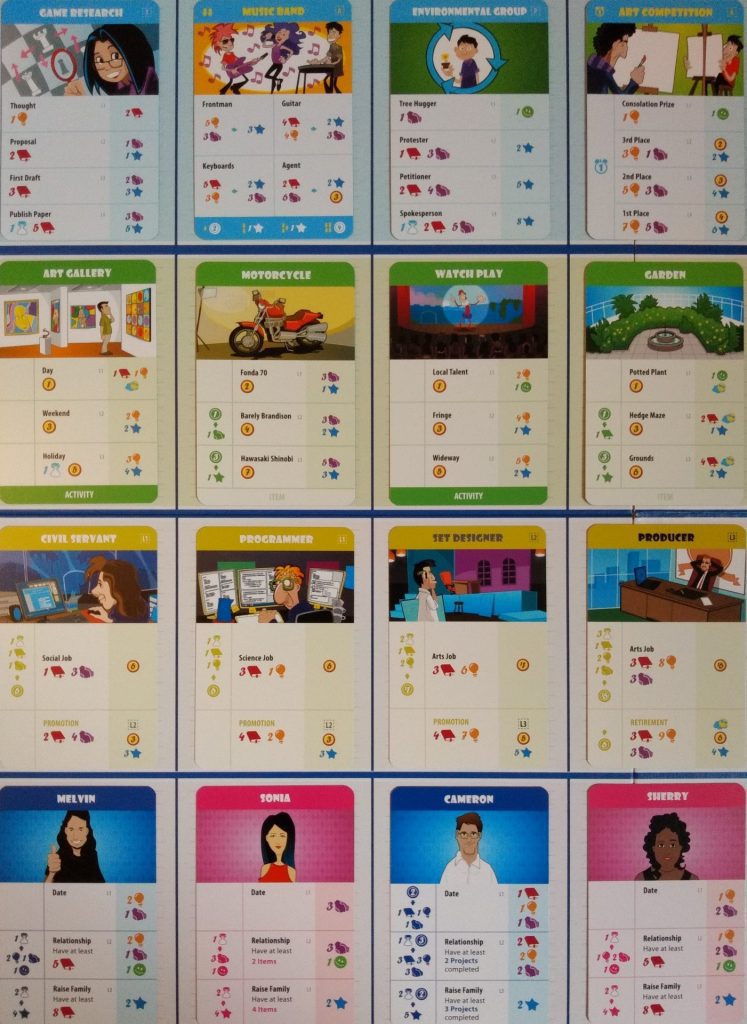

Sure, this sounds petty and in fairness I think the cards broadly do a decent job at conveying information and theme. But when you realise how many cards are on display at a time you’ll see that a couple of font and layout snowflakes become a thundering avalanche of hard to parse information. Here’s the board state in a 4 player game:

Sixteen cards, 7 types of card that function slightly differently from each other (not including different levels and types of Job), over 60 individual resource to reward conversions featuring 210 individual resource/reward icons. Phew! That’s a fair amount of information even just from a static photo and cards are continually taken and replaced, changed at the end of every round and rows can be refreshed mid-round. The sheer volume of cards, card types and options on each card makes navigating the game tricky when you’re experienced and overwhelming when you’re new to it. It can feel exhausting, particularly if you like to analyse every option.

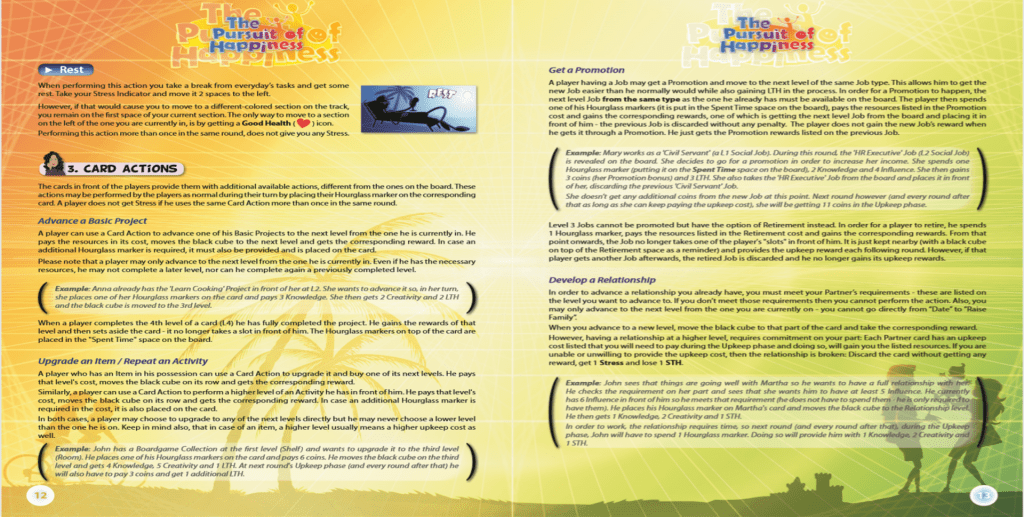

And then there’s the rulebook. I like rulebooks. I will happily sit and read the rules of games I may never play. I never want to look at the rulebook for The Pursuit of Happiness again. Let’s skip over the page colour that resembles what dribbles out of my toddler’s nose and move straight onto the main problem: it’s rubbish. Illogically laid out with dense block paragraphs of text. Heaven help you if you want to check a rule quickly during a game, which you’ll probably want to do as there are a few little rules and ways cards work that can be easy to forget when you first learn the game. Before my first game I read through it half a dozen times and there were still things I wanted to double check online.

“Not how long, but how well you have lived is the main thing.” Seneca.

Moving from production to design let’s discuss one final issue with The Pursuit of Happiness: Death.

During the game you can gain or lose stress from various cards and action spaces. Here’s the Stress track:

You start in the middle and may move as much as you like going right (gaining stress), but reducing your stress is a lot harder – you can only progress within the same colour band. To relax into the next colour band you need to complete a Project that gives you Good Health (a heart icon).

Stress determines both the number of hourglass markers you have (increasing as you become relaxed and decreasing with stress) and your health. Fall off the right edge of the Stress track and you die. For most of the game this is unlikely, but as you enter old age great dollops of stress get slopped on you at the beginning of each round. There are three old age rounds marked on the board but you won’t survive beyond the first unless you get a heart. Getting a single heart can give you an extra hourglass each round and an extra round at the end of the game (potentially two if you get more than one heart, although I’ve never seen this happen).

There are six hearts in the entire game. Six out of 60 Projects.

It’s entirely feasible that other players will snaffle up any hearts that appear before it’s your turn and in a two-player game you may not even see a heart. That extra hourglass each round and extra round at the end feel like a kick in the teeth if you never even had the opportunity.

One of the game’s designers, Vangelis Bagiartakis, has addressed this issue on Board Game Geek and I absolutely get the reasoning – hearts are very costly in terms of the resources and time you need to get them. Whilst you’re slugging away getting your heart, other players are netting Long-Term Happiness points like they’re going out of fashion.

Logically, getting a heart is as valuable as not getting a heart and instead using your time and resources on other more profitable cards. Until you understand this, however, you’ll just feel like the game’s introduced a wild element of chance that’s completely unfair. And the conversion pathways from the various currencies to Long-Term Happiness are opaque enough that it’ll take you a few plays before you understand that balance. If I’m honest, even when you know the logic it can feel frustrating that someone appears to be getting to do more than you, those additional old age round spaces on the board taunting you.

“Every life is a pile of good things and bad things. The good things don’t always soften the bad things, but vice versa, the bad things don’t always spoil the good things.” The Eleventh Doctor.

These are all issues you may stumble over on your first couple of games but despite them I think The Pursuit of Happiness is a pretty great game and I absolutely recommend it. It’s a greatness that comes about when you step away from cold analytics and embrace the theme, because how The Pursuit of Happiness uses its theme and marries it with the central mechanics is fantastic.

It’s hard not to reference The Game of Life when discussing The Pursuit of Happiness. These days there’s a wide spectrum of board game themes beyond the stereotypical fantasy, farming and trading tropes – board gamers can be space lions, vengeful gods, mysterious manors and almost anything in between.

Yet tabletop games covering the day-to-day of real life are few and far between. I can count them on one hand – The Game of Life, CV, The Pursuit of Happiness and Fog of Love (which is more relationship simulator than a life simulator). There are more board games about the discovery of evolution than real life.

As a result, The Pursuit of Happiness feels refreshing and special in a way that few games do. And whilst it largely boils down to using any of the game’s various currencies to obtain and advance cards, the stories that emerge naturally as a result are incredibly strong. Importantly, the harder you lean into the theme, the more you’ll get out of it.

During a game I regularly make decisions that are suboptimal in terms of pure points but are equally rewarding in terms of my character’s narrative. After a game it’s not unusual to spend a while discussing the characters created, how they reflect (or don’t) the players and how they might have interacted with each other.

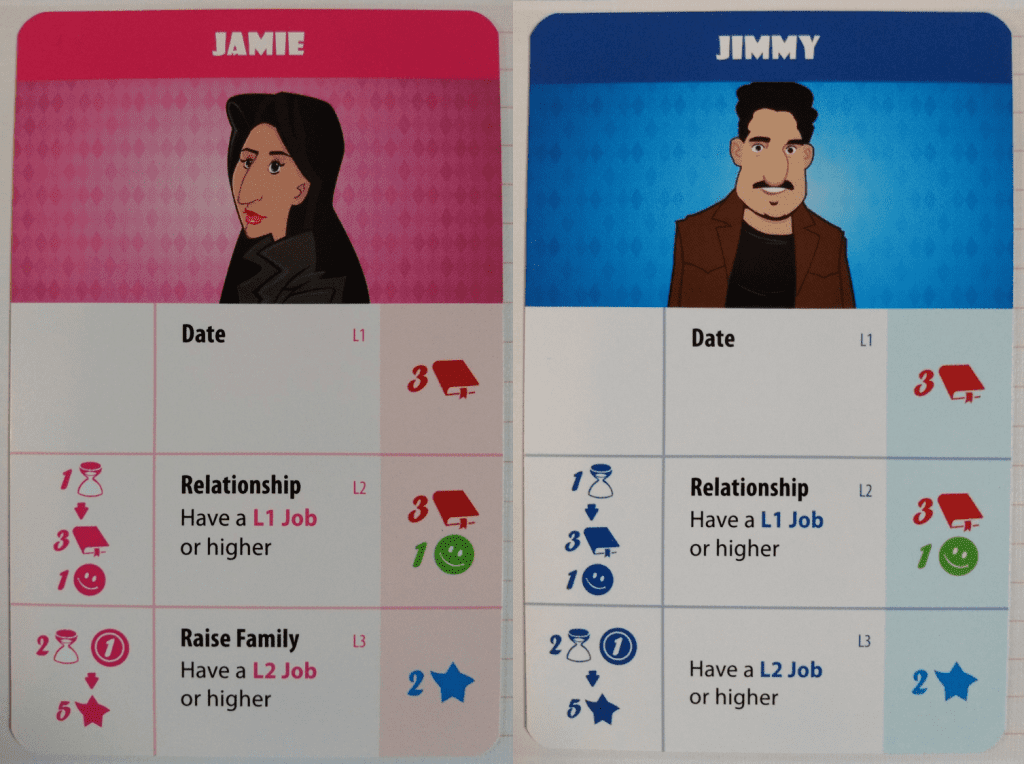

The theme runs through every turn and element of the game, from the mechanics and decisions you make to the flavour text and artwork. The art is full of character and energy yet generic enough to allow you to get into character if you wish (the people could possibly do with a little more diversity, it’s not bad for representation but it could be better). The Job and Partner cards are all double-sided, they do the same thing but provide options for different roles and genders. I chose to start a relationship with Jimmy because of his moustache and because Jamie on the other side of the card looked like she might be a bit too pedantic for my character. Did it make any difference to my final score? Absolutely not. Did it make a difference to my experience and enjoyment of that game? Absolutely.

“Time is the most valuable thing a man can spend.” Theophrastus.

I’m a sucker for games that use time thematically and mechanically. There are the time tracks that determine player order in games like Thebes or AuZtralia (I’m purposefully not mentioning Patchwork because you could swap time and buttons around and wouldn’t notice a difference). There are the turning cogs of Tzolk’in that require players to carefully plan the timings of their moves rounds in advance. There are real time games like Escape: The Curse of the Temple or Pendulum that ask players to manage actual units of real-life time. And there are games like Village where time is a resource to be managed or manipulated, and affects the lives of the people within the game.

The Pursuit of Happiness uses time as well as the best of any of these games. Time is always limited, sometimes cruel and requires players to manage their character’s lives carefully. There are four main currencies in the game (Creativity, Knowledge, Influence and Money) but time acts as a fifth – it’s both the method of doing anything and an additional resource for achieving those things that are especially worthwhile.

I finished one game with only four hourglasses going into the second old age round. I spent two of them on my job and two on my family – my final round consisted of me actively doing nothing other than maintaining what I already had but it made utter sense for the game I was playing and I very nearly won. Importantly, the decision not to quit my job or abandon my family was mine, and interesting both in terms of the options for points and my experience of that final round.

“You only pass through this life once, you don’t come back for an encore.” Elvis Presley.

Like with its use of time, the rest of the mechanics support the theme to create a game that you can improve at with each life lived, getting to know the game’s finer details. There are great stacks of Projects and Items/Activities cards for you to discover over repeated plays that provide a wealth of narrative options (although they do trend towards the geekier lifestyle). And whilst not wholly original even in 2015, the central mechanics are tweaked to the game’s advantage, deviating subtly from the typical worker placement crowd.

Once you’ve got over the initial hurdles of learning the game and learning to interpret the board state everything becomes a lot smoother and your gameplay enjoyment equals your narrative enjoyment. There are points in every single game where I get so wrapped up in the gameplay and theme that moving up the Long-Term Happiness track causes a flush of genuine real-life happiness – not from an especially clever move but a satisfying and consequently rewarding life.

“You have brains in your head. You have feet in your shoes. You can steer yourself in any direction you choose.” Dr. Seuss.

I think The Pursuit of Happiness is pretty great, but would it be a great game for you?

If you think you might enjoy The Pursuit of Happiness then you probably will, just watch out for that first game trying to put you off.

If the narrative aspect is less important to you then I think it’s a good game and worth a try but you won’t be getting as rich an experience and you’re probably better spending your cash elsewhere.

If you want to play a version of The Game of Life that allows you to be smarter and more creative then The Pursuit of Happiness is absolutely the game for you – it will reward you tenfold.

“To live is the rarest thing in the world. Most people exist, that is all.” Oscar Wilde.

For more content on The Pursuit of Happiness, read our review of its 2 expansions, Community and Experiences.

Beautiful. I will have to discuss this one with my wife — I think she would love it!