Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

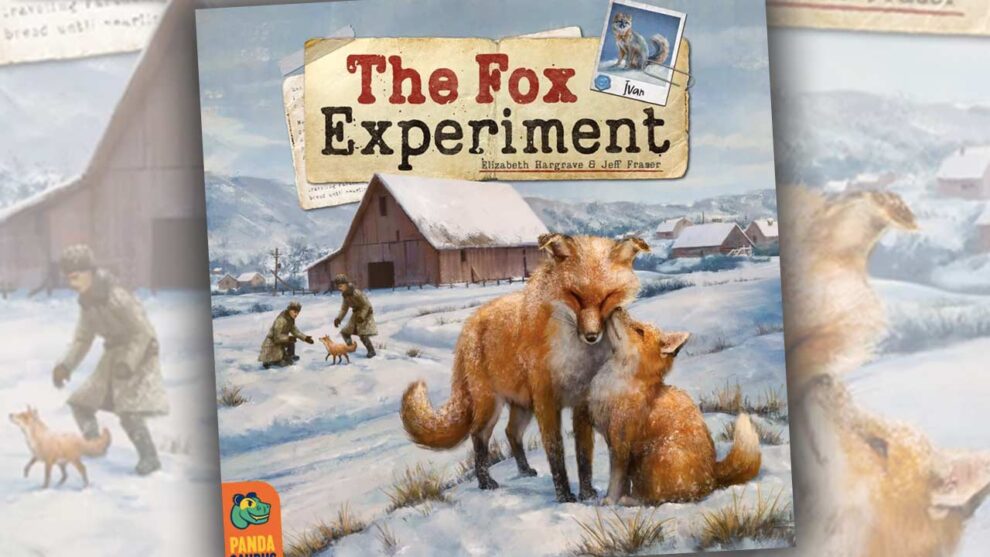

The Fox Experiment is an intriguing title. Perhaps academic and armchair geneticists perk up at the low-key mention of the fox domestication study that began in the Soviet Union over sixty years ago, but there’s something here for the Average Joe as well. Both story and backstory are fascinating: researchers attempting to breed docility in otherwise wild animals (though not animals from the wild, as it were) and a scientific posture that refused to get on board with Mendelian genetics out of nationalistic loyalty.

If that doesn’t scream BOARD GAME, I don’t know what does.

Co-designers Elizabeth Hargrave (Wingspan, Undergrove, Tussie Mussie) and Jeff Fraser (Cartouche) have sought to capture the unusual nature of this story in The Fox Experiment. Players compete as researchers, breeding foxes in search of certain physical traits. As the story goes, the traits in question manifested alongside the same hormonal balances that coincided with the tame foxes. Find the traits and you may have found the friendly fox.

Players begin by selecting a mom and a dad and letting a few dice fly to see which traits manifest most forcefully. That first round is like the slow ride up the chain. From there, gravity kicks in, sending researchers into a genetic double dip with a loopty-loop tossed in for good measure.

Five and a half wonderful wild animals

Each of The Fox Experiment’s five rounds begins with a draft of three items: a mom, a dad, and a place in the next round’s turn order. Players make their selections in turn order, but may choose whichever of the three seems best. This little decision is no little decision at all. The right parents lend their needed traits via dice, and a player’s place in line might just make the difference in the end.

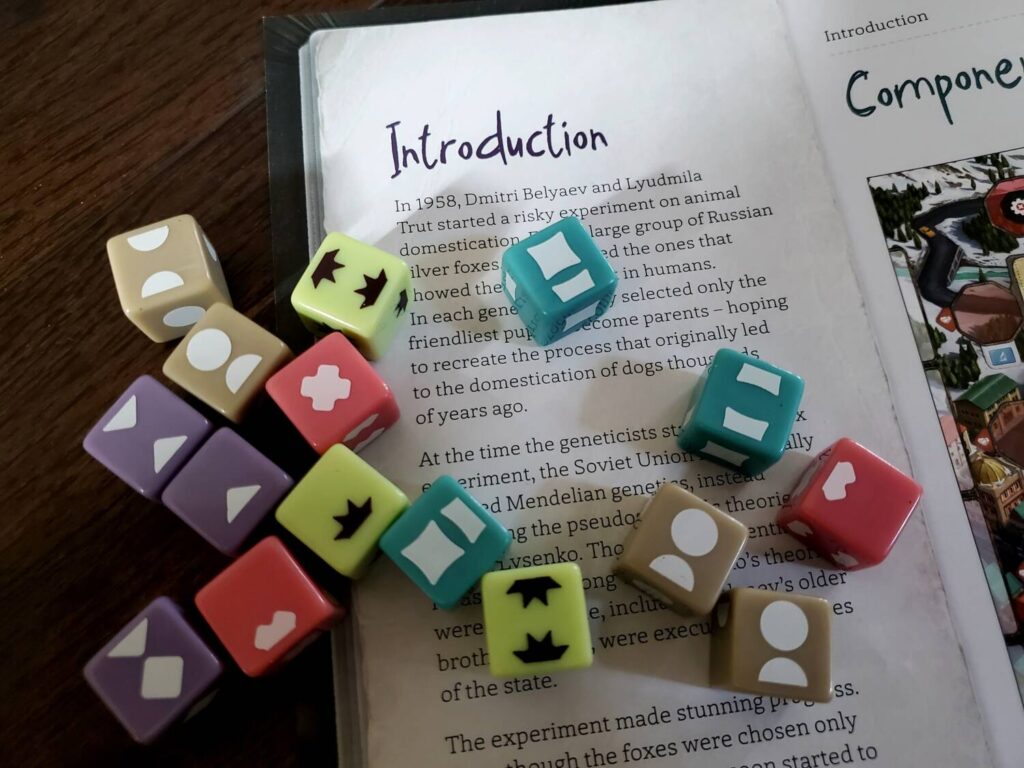

Breeding is next on the agenda. For each parent fox, players receive dice whose sides depict whole- and half-symbols (plus the cherished one-and-a-half face). These symbols represent traits in the foxes. In the first round, parents bring one, two, or three dice each to join a player’s stock of wild dice. In the fifth round? Brace yourself; but I’ll come to that.

Players roll the dice and arrange them so as to create the best combination of traits. Half-symbols arranged side-by-side become whole traits. Wild dice can be used to complete those half-symbols as well. The result is a mixed and matched genetic train from which players then write the results on a pup card with a dry-erase marker.

There are aims with these pups. Study cards demand particular trait combinations in exchange for endgame scoring. In addition, some of the trait markings grant tokens that serve as currency for purchasing upgrades. Finally, the sum total of markings generates a Friendliness score, with the highest tally earning a bonus for the round. Most importantly, the pup must also be given a name before sending it out to the kennel as a parent for the next generation.

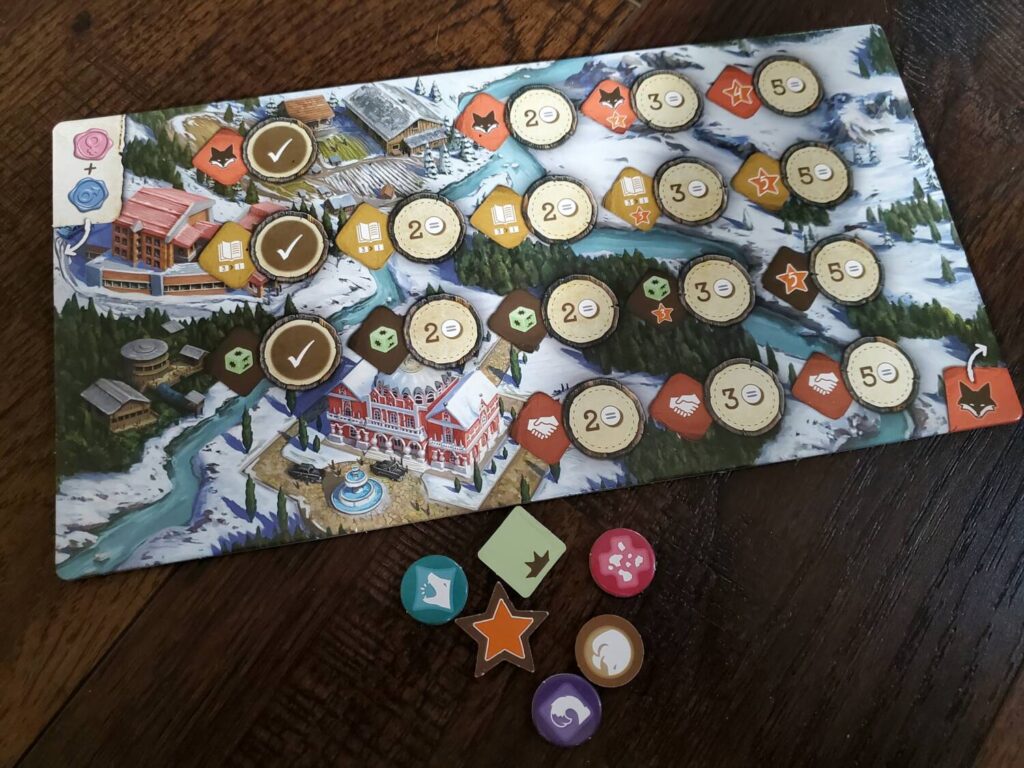

Players purchase upgrades from their boards using sets of matching tokens. Breeding a second and third pup each round allows for greater movement in the Studies and a better chance at tokens. New Study cards mean a better chance of producing a fruitful combination of traits. More wild dice mean more wild dice. Lastly is a set of public scoring objectives that give an instant resource bonus and a boost in the endgame. Essentially, upgrades can be purchased any time except during the dice-chuckin’ breeding phase.

As the pups go out into the kennel, the game’s economy starts to run wild. Where the base parents give a maximum of three dice, the pups have the potential for eight. When players breed multiple pups they reroll for each one, introducing more and more superpups to the gene pool as the game progresses. By the fifth round, it’s not uncommon to be rolling sixteen or more dice (don’t forget those wilds) for each new pup, creating long strings of traits bolstered by special abilities and extra wild tokens (which I’ve not even mentioned yet). To say The Fox Experiment picks up steam would be an understatement.

Points come from the Study cards, the player board, the public objectives, friendliest pups, leftover ability cards, point tokens earned from pushing traits beyond the card max, and leftover tokens. Sixty or ninety minutes later, the rush is over.

Are you cussing with me?

The Fox Experiment is a little bonkers. Ninety dice greet you upon opening the box, and by the fifth round most of them are in play. There’s an absurdity to rolling seventeen at a time, but that is the spirit of this endeavor. Chaining the lot together to breed a pup or three is the mechanic that occupies the most time in the game. I have to admit it’s satisfying.

Where the dice provide the fun, the draft is easily the most compelling phase. There are always beefy parents in the kennel or parents that better serve your specific aims. Claiming turn position is also crucial. It’s nice to get additional rewards for choosing a later position, but there is no substitute for having the first crack at an early superpup. I appreciate the tension.

The game’s overall rhythm is also satisfying. Heads up for the draft, heads down for the breeding, heads up for the crowning of the friendliest pup. Though the bulk of the time is spent on your own business, the game does draw you back to the center often enough and with good purpose.

I think naming the pups is the most amusing aspect. In the strangest way, this little exercise gives players a stake in the narrative arc. When you send Jan and Marcia to the kennel, it’s like saying goodbye to a friend. When you are forced to choose between Ali and Frazier, it’s personal. And there is an inherent sadness as you send little Kurt, Courtney, and Frances Bean out into the world, for you cannot bring these siblings back together without paying the genetic cost (literally, there is a penalty for incest). As the game wears on, players loosen up and start letting their personality—or at least their streaming, reading, and listening habits—leak onto the cards. It’s the right sort of laughter for the tenor of the game.

When breeding multiple pups, each pup can serve to advance players in their Studies, making those extra cards an early necessity. The extra pups do not provide endless tokens, however. Across the litter, only the best pup for each trait grants its booty. This limitation creates an intentionality in every litter, an attempt to maximize the pups for their output. When that handful of dice hits the table, there are goals and strategies: how to arrange, when to spend extra wild tokens, when to push each particular trait.

I’m going to lose my temper now

But, to borrow a word from our very own Andrew Lynch, The Fox Experiment is generous—almost too generous. With a dozen or more dice at your disposal, the game doesn’t need to offer much for luck mitigation. The dice will bear fruit. It may not always be exactly the wanted fruit, but there is enough to go around. Any feelings of disappointment will come not from failure, but from an unplanned bout of success.

I can’t help but draw a comparison to 2022’s smash hit Flamecraft. In terms of mechanics, the dragons have almost nothing in common with these foxes. But the games both suffer from loose economies. A friend of mine is often fond of asking what games would be like if there were no governors on the bounty—what if designers just let the game’s hair down? Titles like Flamecraft and The Fox Experiment are the answer. Resource floods shift decision-making away from struggle and toward accounting and maximization. Bounty isn’t bad, but it creates more of a romp than a tense battle.

I can handle wading through the bounty, but this particular economy bothers me for another reason. Having played four times now, I have already begun to notice a pretty consistent spending pattern. 1) Get an extra pup; 2) Get an extra die to make the pups sweeter; 3) Get an extra Study to catch the overflow. Then do it again, but make sure you have an eye toward those public objectives because you’ll want to dip your toes in those waters by the final trigger.

Despite different players and player counts, there has been little deviation. Now the flipside, much like Flamecraft, is that the specific flow of traits and resources will probably vary from game to game—the how will always be on the move and there is something interesting there. But the what, the overarching flow of decision-making, will likely remain the same. I can see some growing weary of the progression and moving on, even as I can see some loving the dice and the markers so much that they come back again and again just to see how it plays out.

As much as I love naming pups, I wish players could only get two just to rein the belt in one more notch. The player board is arranged such that the early purchases are all upgrades and only later spots give points. Progression is always left to right, and therefore always happening the same way. If there were some genuine freedom and/or variety in that board, it might make the decisions more interesting or less predictable. As the game stands, it is good. I can’t help but think it could be just a little better.

While I’m wearing my critical goggles, the two-player variant is not nearly as enjoyable because of the introduction of an AI opponent. The dummy figure pulls the two-player game into a four-player setup, then proceeds to siphon away choices in the draft, adding dice to those stolen foxes for the next round. The mechanism simulates breeding better pups and forces player choices, further cementing the commitment to the bonkers economy. In my head, though, it would be just as easy to jettison the AI, draft from fewer cards, and add a die to the losers for the next round for the sake of ease. After the first round players are likely to choose from bred pups anyway. Without some simpler house rules, I would stick to three or four players.

Pensez-vous que l’hiver sera rude?

Despite my reservations, I think The Fox Experiment is worth playing until it can’t be played no more. The aesthetics work. The draft mechanism is engaging. Handfuls of cool dice are fun, and the arrangement is an interesting exercise. Naming the pups is stellar and the dry-erase components are superbly made. The history behind the game gives the experience a decent story arc, and the theme shines through in all the right places—especially considering the chaos of the many, many pieces in the box. The rulebook is clear, with page references on the back to lead and guide the forgetful or the confused. I’m not sure how long it’ll stay in our collection, but we’ve had a lot of fun with it so far.

It is fitting that the aim of breeding is friendliness, because that’s exactly what The Fox Experiment pulls off. It looks nice and it plays nice. Some might say too nice or predictably nice, but for the resource management lovers, I think it’ll have the characteristics they’re looking for.

Add Comment