There are games with flawed rulebooks. There are games with unfortunate misprints and iconographies that make you second guess yourself and the production. There are even games whose endings seem fraught with inconsistencies that make you wonder if you’ve missed something very important. When a game, rarely, boasts all three, I have no choice but to ask:

Why do I like The Flow of History as much as I do?

Get thee a government

The game’s sixty-seven cards are divided into six types and span five Ages. The heart of The Flow of History is the bidding mechanism by which players gain these cards. Players declare their intentions by investing resource tokens on a card and waiting for the investment to clear on a forthcoming turn. Opponents have the option of sniping that investment, though, compensating the investor and instantly claiming the card. This means investments may not be investments at all, but rather deft machinations designed to entice neighbors to act rashly in exchange for compensations and a smug sense of control.

When an investment succeeds, the goofy iconography kicks in. Potentially, cards have icons in three places: across the bottom, in the center, and under a magnifying glass north of center. Upon acquisition, the icon depicted under the magnifying glass is counted everywhere else in a player’s tableau. Every match gives one resource back, presumably for tying relevant innovations together. Players then also trigger the iconography in the center of the card, which might initiate a military strike, resource gains, a bit of extra cardplay (acquiring or discarding), or simply bolster those countable icons.

Should an opponent snipe an investment away, the whole magnifying bonus bit is forfeit. But the card’s central ability and any lingering helpful iconography remain. Cards join a player’s tableau in columns based on type, stacking from bottom to top, each card covering all but the bottom icons of previous cards in the process. In this way, various aspects of a player’s capacity grow, shift, and shake throughout the game. Governments develop and evaporate, technologies rise and fall, militaries kill and, well, kill.

One icon depicts a handshake. Any time a card is sniped away, players gain resources equal to the handshakes in their civilization. This is in addition to receiving the compensatory resources from the sniping sniper.

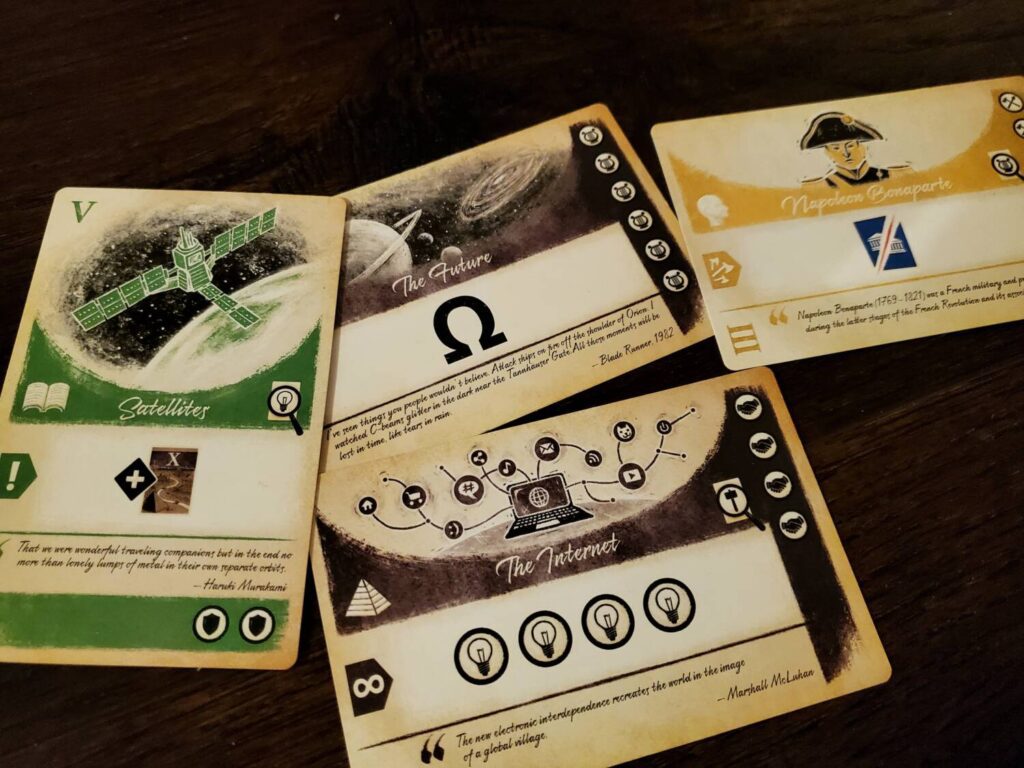

And so it goes. Players gain and lose, invest and snipe until the deck runs out. Then the strangest little ending occurs. There are two cards at the bottom of the deck. One is The Internet. The other is called The Future. Each is highly lucrative, but not entirely attainable. If at any point The Future enters the game, either to the market or to a player via a card draw, the game ends immediately. There is no straight investment action for The Future.

In teaching the game, I am a firm believer that you must not only show these cards, but explain how one might obtain them during play. After all, there are only so many opportunities to draw from the deck without a bid in the course of history. Two cards of the 67 are highly sought after when it comes to The Future: Christopher Columbus, who can be trashed on any turn to gain the top of the deck, and Satellites, a card which grants a free draw upon acquisition. Of course, Confucius might come in handy as well for his ability to sacrifice himself to gain another leader. You see how the chain starts to form. It’s entirely possible to win The Flow of History without The Future. But there are necessary steps for players interested in trying for that prize.

The one action I failed to mention, the action that works in conjunction with the ending to raise another potential complaint, is the Harvest. There are fixed resources available. During a Harvest, players add more resource tokens to the game (equal to the number of leaf icons in their tableau) before acquiring half of the supply (or an amount equal to the current age when the supply is lean). This necessary and beautiful action is always available, even as a turn between investment and acquisition. It adds an element of careful—and sometimes dumb lucky—timing to the global endeavor. Of course, pausing to grab cash might result in getting sniped. Then again, maybe that was the plan all along?

The Turmoil of Time

The game sounds fine, Bob. What is the big accusation? King-making, of course. Imagine with me: The Future is in sight—literally, it’s the next and last card. Confucius was spent to gain Ghandi or John Lennon. Columbus gained some major wonder in the name of a points boost. Satellites popped out early in the final Age, so we’re going to end by conventional means. The next successful bid will bring The Future into the game and trigger the end. Players begin deferring their turn, harvesting and stockpiling tokens, refusing to invest, waiting to snipe the final card and end the game in their favor. Action stalls. The game, and the world, are dying. What do you do?

The game needs some sort of a “no harvest once the Internet appears” rule or a “once everyone harvests in succession, the game ends immediately” rule as a failsafe. Something. Anything to force the issue. Between this and awkwardly planning for The Future, The Flow of History has duly received its share of criticism.

At first, I wanted nothing more than to “fix” the end. I tried letting the round of turns finish out. I tried house-ruling The Future. Folks in my circle tend not be so concerned with winning that we refuse to take turns at the end, so the king-making issue has never really come up. We’re happy to chalk up the ending to fate. After quite a few efforts, though, I settled down and learned to love the ending.

The rulebook refers to players as “the invisible hand shaping destiny.” I’m not sure about that, but the nature of the end and the deck means the game works best when players are familiar with this particular course of history before the drama takes to the stage. When all the players know the cards and the events that will alter the game’s narrative, the fight (and the anticipation of the fight) around those tipping points is what gives The Flow of History its charm.

As another example, when a player claims Communism as their government in the fourth Age, all the uninvested resources in the game are brought into a pile and evenly redistributed. Depending on the economy of the moment, beads of sweat form on several brows. Knowing it’s in there imposes a psychological effect on the hoarder at the table. Or take Napoleon, who attacks everyone when he rises to power—just knowing he’s en route forces everyone to prepare or suffer consequences. Pure reaction was fun when we were all ignorant, but familiarity has proven far more interesting.

I love that there is only one tangible resource in the game. Every time I play I’m impressed at how much is possible without delineating food and metals and oil and stone and sheep and on and on. Yes, there are icons to gather and count, but The Flow of History bears a simplistic shine on the table with its one token resource.

I have the deluxe version, which means that singular resource is a chunky little coinish metal bit and the player pieces are molded towers with a wonder-ful aesthetic. The deluxe version is hardly necessary, but I’ll admit I’m happy to be slinging coins rather than simple wooden chits.

I would love an expansion. A few years back I might have said, “to fix the ending.” But now I think I’d just like a few more of the people, places, events, and inventions of history to show up from time to time. It’s easy enough to remove a card or two from each Age to maintain the numbers in the deck if another packet enters the fray. In fact, we’ve tried removing cards at times to shorten the game. The only catch is, you can’t remove Satellites or Columbus. To do so would break the experience entirely.

At a couple points I’ve wondered if this title would leave my collection. But then someone breaks it out and my affection deepens for it. Or I’ll spot it and realize I’d like to play again since we all know a bit more about the cards every time. We chat about the cards we’re waiting for throughout the game. Oohs and Aahs greet the favorites (and the least favorites). And as the fifth Age dwindles and we see the edges of The Future appear, we shuffle in our seats.

Familiarity means our games are faster and tighter. We know when to stop worrying about The Future and when to hunker down and go for it. We chase the nation we want to be, bend our plans to the whims of fate.

Of all the games in my collection, The Flow of History is probably the one that I can say has won me over most dramatically. It may not be the best civilization game out there, but it accomplishes much for a small box if you give it the time. I celebrate any game that gets stronger the more I see it.

I have only a few civilization games in my collection these days (I cannot tell you how much I miss Civilization and Advanced Civilization). The ones I still have are good — this one sounds like something I will have to try.

Great review! Thanks.