Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

There is a unique pain involved in realizing the sorts of effects a game is supposed to invoke, only to then watch in vain as round after round passes in relative boredom. There is a related pain in attempting to force said effects, only to experience the same disappointment on a wholly different level.

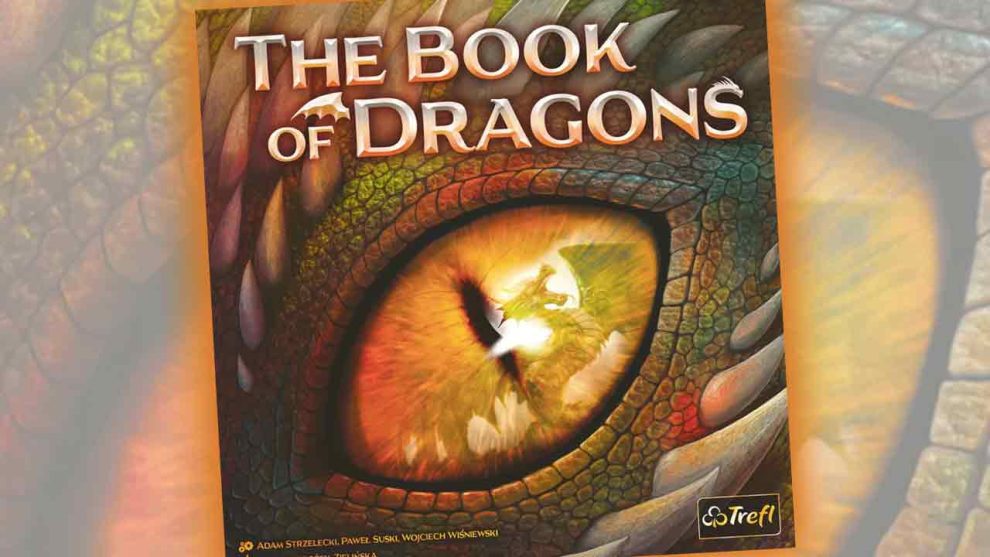

Meet The Book of Dragons, a title from the design team of Adam Strzelecki, Pavel “Bloski” Suski, and Wojciech Wiśniewski. The Book of Dragons is a fixed-placement auction game from Trefl in which players are adventurers purportedly collecting evidence of various dragons for enthusiasts the world over.

These scaly critters had me thinking. Sadly, I was thinking about games that produced their desired effects with a bit more panache.

Enter the Dragon?

The board is a tidy three-piece puzzle with spaces for piles of cards determined by the player count. The cards each contain one of six dragon types set atop a background color and a corresponding point value. Across the top, those backgrounds are pictured with icons indicating a single-use special power.

Players receive three dice to serve as trackers—there will be neither rolling nor chucking with these dice—along with a card indicating their preferred dragon type and a lock token. The dice are set to starting values of three, four, and five.

Turns involve either bidding or claiming. Each pile on the board is marked by a number of pips that serve as the minimum bid. Players can bid on any number of dragons, provided they can lay the minimum number of pips and best any bid currently on the card. If one player outbids another, the ousted bidder increases their bumped dice by one each. If a bid survives until the next turn, the dragon comes home to roost.

Dragons are worth the point values on the cards, but those point values also indicate a one-time ability which can be exercised at any time during a turn. The abilities are laid out inverse to the point value, giving a hint of compensation for the weaker score. The three’s ability to lock out other bidders from a dragon is quite nice. The four can flip any die to its opposite side, making a one into a six or a two into a five.

Depending on the player count, the game ends when either one or two piles are emptied. Players score their dragon values and any bonuses from collecting their preferred dragon.

The Way of the Dragon?

The Book of Dragons should work, but it doesn’t. At least, not for me.

I really like the idea of the auction here. Win if possible. Collect the spoils if unsuccessful. I really like the idea of sniping dragons out from under other people, even though it means they receive compensation. I’ve seen these ideas before.

I couldn’t shake thoughts of The Flow of History, a civilization-building auction game that features a truly enjoyable (in a maddening What have you done to me!?! sort of way) sniping mechanism that issues delightful consequences all around the table. I remember it because I think that’s what The Book of Dragons was going for with the whole bumping endeavor. The trouble is, I never found myself asking What have you done to me!?! I just… moved on. When a loss doesn’t have any bearing on strategy, it’s just a worn speed bump.

The dice placement is designed to create an economy of sorts, where players lose (intentionally) in some places to adjust the value of their dice while asserting themselves in others to bring home dragons. This is not unlike Furnace, a title I reviewed recently which works to near perfection. Where our fiery friends fall short, however, is in the fact that there is little incentive, time, or reason to lose auctions on purpose in any consistent or meaningful way.

The Book of Dragons is designed to last less than a half hour, a boast which holds true for the most part, even at higher player counts. With little more than a dozen turns passing in that time frame (closer to twenty in a two-player affair), and a fair number of dragons likely needed to win, where is there room to lose? Perhaps one die can be tossed off to lose while two are placed in hopes of victory, but a boost of that single pip holds marginal value in the grand scheme.

There are two problems with this scenario: In two and three-player outings, a tedious game of ping pong occasionally breaks out as dice are bumped and bumped again in redundant turns until one player cannot out-do the other in battle over the highest scoring dragons. The rules include a two-player variant that adds a roving die, ostensibly to eliminate this tedious contest, but it never goes away entirely. When players tire of the rubbery match, they simply start bidding on different dragons.

In the high player counts of four and five—where I truly believe the game comes close to shining—players are, in theory, better able to spread their dice around in hopes of those consistent small gains. Rather than reciprocal gain, though, the back and forth typically ends when a player on the other side of the table drops all three dice and stakes an insurmountable claim. That’s when the ol’ metaphorical light bulb seems to turn on strategically.

Players have been far more likely to load a card with all three dice than bother with the slow process of boosting through hopeful bumping. When players load cards, other players are more likely to do the same on an adjacent card rather than engage in a battle that will grant a triple bump in exchange for a triple loss when the card is inevitably won. In multiple games, a silent contract of sorts formed as players agreed to utilize decreasingly valuable dice in unison and count on flipping cards for strength. Yes, players forsake the contract at opportune moments, but it’s easy enough at that point to just… move on.

Truth be told, since the game isn’t terribly long, the card abilities are often enough to side-skirt the bumping economy. Raising each die by one pip for flipping a five, or just a single die for flipping a six become more attractive instantaneous and practical options. Flipping a seven for the timely discard of a valuable dragon is far more effective than the effort required to win the auction for that dragon. I suppose this is the point of the design, but that doesn’t make it any more exciting. More often, it falls prey to the trap of far-too-obvious decisions.

Game of Death II.

I believe there are folks who will truly enjoy this one. But it’s definitely a subdued sort of enjoyment. It is easy to explain, swift to play, and might include some interesting decisions. It is a simplified precursor to quite a few other games and may serve as a gateway to the mechanism.

My youngest kids like it, but they just pile three dice on a dragon without thoughts of consequence or strategy—because they can—and we race to the finish. My older kids were a bit bored by all the dice turning and the general lack of pulse-pounding tension present in the other games I mentioned. They were racing to the finish as well, but not for the best reason. We had pleasant games, but none were begging to play again.

Personally, I’ve tried to engage the board with differing strategies just to shake it up and see what The Book of Dragons has beneath the surface. Eventually I find myself dropping three dice for my preferred dragons and those precious high-value critters, relying on the cards more than the auction for assistance. I say again what I said before: I really like what this game is trying to accomplish. At the end of the day, though, there are other auctions in which I’d rather be bidding and losing—games that accomplish in full what the Dragons only provide in part.

I saw a comment on BoardGameGeek from a Polish player: taka sobie. Google translate (my apologies: though I have a Polish name and Polish roots, I’ve yet to venture into the language) tells me this means so-so. I think that about sums it up for The Book of Dragons.

Add Comment