Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

During an interview on the podcast 5 Games for Doomsday, designer Mark Herman discussed two different approaches to historical board games. He said that games can work like simulations, recreating the events more or less as they happened, or they can work to put you in the headspace of that moment. To illustrate his point, he used one of his own games.

In Empire of the Sun, which depicts the Pacific Theater during World War II, neither player knows if the atomic bomb will come into play. It’s possible to go an entire game without seeing it. Why does that matter? In real life, neither Japan nor the vast majority of the U.S. military knew about the bomb, until suddenly they did. If either party had, they would have made different decisions.

If Harry Truman knew about the bomb before he did, the United States Military and other allies wouldn’t have planned an invasion of the Japanese mainland. If Japan knew the United States had the capacity to instantly end the lives of some 80,000 people in Hiroshima, to say nothing of people who died later from hunger, injuries, or radiation sickness, they may well have surrendered earlier, or never entered the conflict in the first place. To play knowing that the atomic bomb is coming is to fundamentally alter the decision-making landscape of the experience.

I think about that interview regularly, because it says something important about thematic elements in board games, and how we approach them. “There was no atomic bomb!” is a criticism any number of players may level at a game like that. “It isn’t accurate.” Accurate? Maybe not, but it is deeply thematic. Is thematicism fealty to the facts of the matter, or is it about the headspace you’re in?

To me, the latter is more important.

Time of Cris-tricks

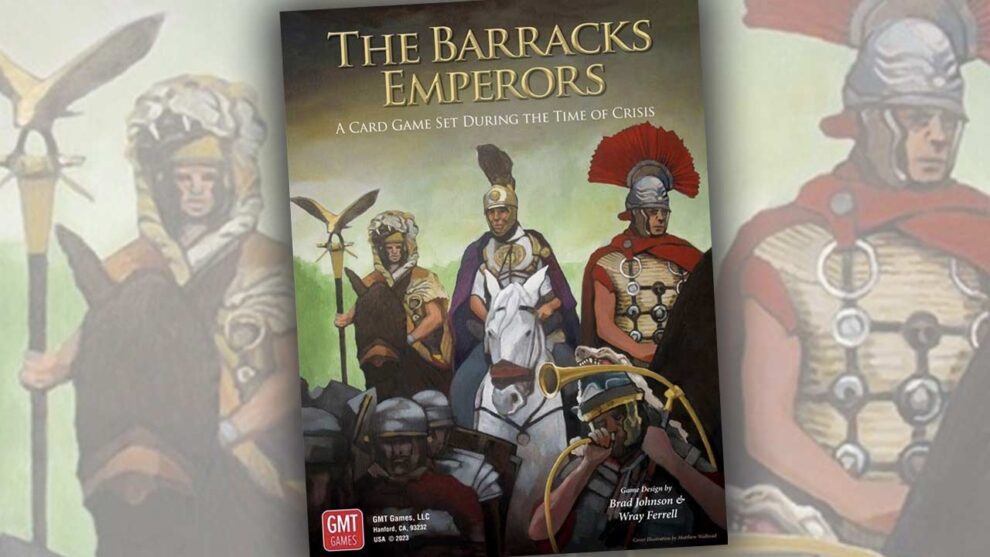

By that metric, Brad Johnson & Wray Ferrell’s The Barracks Emperors is pretty dang thematic. It takes place in Rome during the 3rd century, a notoriously calm, level-headed time. Rome was going through emperors in much the same way that I burn my way through a Costco container of peanut butter pretzels: by the handful, and often several all at once.

There have been many games centered on this period of history, including Johnson & Ferrell’s own Time of Crisis. The Barracks Emperors presents as the least likely representation yet. The game is played on an irregularly-shaped grid, plopped over a map of the Roman Empire. I say “plopped” intentionally. There’s no relationship between the grid and the map.

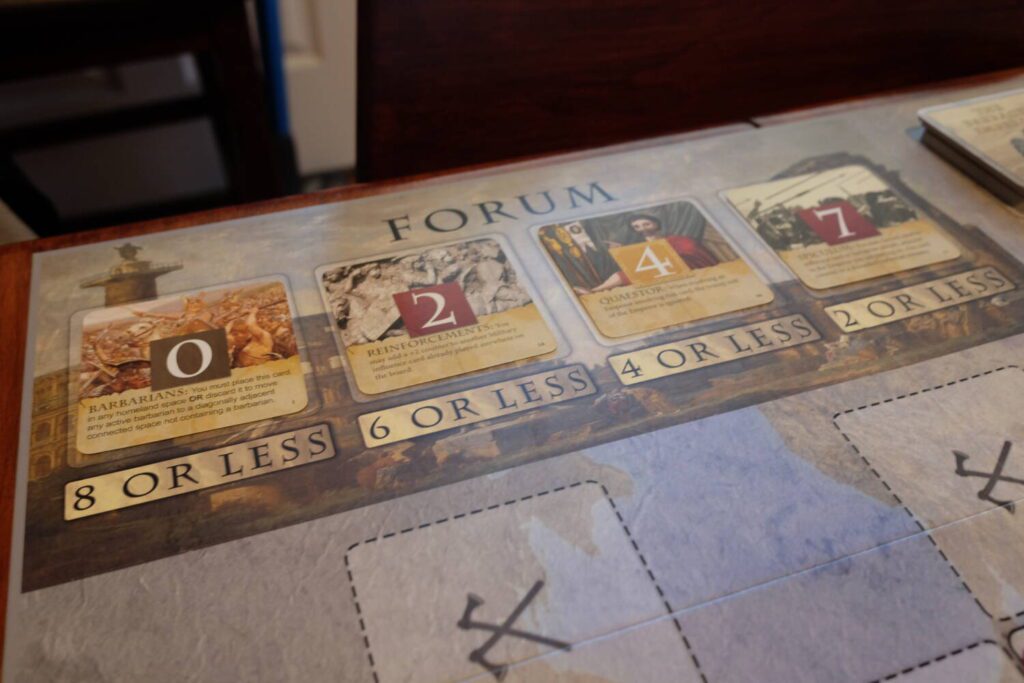

Each round, 13 Emperors are dealt out to the board. Each player receives a hand of cards, with more added to the market. On your turn, you play a card to one of the spaces in between the various emperors. The goal is to collect as many Emperors as possible, which is done by having the highest-value card adjacent to an Emperor when his surrounding spaces have all been filled, or the highest adjacent card in the Emperor’s own suit, which functions as a trump. At its core, The Barracks Emperors is a set-collection game, where points are awarded for each Emperor, and for sets of one Emperor in each color.

Each player has a cardinal direction, which imposes limitations on your placement options. If you’re the North player, you can only play cards to the North side of an Emperor. Mind, while you play that card to the North of one Emperor, there’s a pretty good chance you’re also playing it to the East of a different Emperor, and the West of another, and the South of yet another. This is where the brilliance of The Barracks Emperors starts to unfold, as you have to weigh the risk of feeding your opponents powerful cards.

Higher isn’t always better. It’s situation-dependent. Most cards have an ability that triggers when played, or that stays in effect. Some modify the value of other cards, or neutralize the trump suit. Others allow you to move cards, switch cards, cover cards, take cards, etc. The interactions of the card abilities with the board state create the meat of The Barracks Emperors, and make every turn rich with possibilities.

Order in the Chaos

The Barracks Emperors is remarkably and keenly focused on rewarding skill and attention. Most of the design choices seem to have been made with mitigating bad luck in mind.

First, there’s the fact that your most powerful card placements will also likely help others. Then there’s the fact that lower-value cards have more powerful abilities. On top of all that, you refill your hand from the card market, which is open information and has its own restriction: the stronger the card you play on your turn, the fewer and the weaker the options you have in the market.

Once you’ve played enough to develop a meta, and to have a casual familiarity with what cards are out, The Barracks Emperors is about as close to luck-free as a card game can get. It’s hard for someone to become the runaway winner unless they’ve earned it. At that point, you really only have yourself to blame.

Four to the Floor

Let us speak practically for a moment. While The Barracks Emperors can technically take anywhere between 1 and 4 players, it’s a 4-player game. Much like The Princes of Florence, which shoots into the stratosphere at the maximum player count, The Barracks Emperors doesn’t reveal the full extent of its insanity until you have a full table.

It is certainly one to avoid if you are prone to analysis paralysis. I walked away from each game exhausted, in the best sense. Having a need to consider every possibility would grind this game to a halt, and it’s already going to be long for your first play or two. While a table of seasoned players could easily swing a full session of this in about 60-80 minutes, the learning game starts out slow and overwhelming. It doesn’t help matters that publisher GMT has once again created a reference book rather than an instruction manual. I love GMT, but I’ve never known a publisher less interested in making the learning process for their games approachable.

Is The Barracks Emperors for everyone? No. It is perhaps too abstracted for GMT’s usual audience, and too GMT for everyone else. It’s brainy, it’s hard, it’s crunchy, and it’s kind of magnificent. What it is, unequivocally, is for me.

The Barracks Emperors is a deeply successful evocation of its setting. You can plan all you want, but strategy will only take you so far. In a time of such turmoil as the 3rd century, you have to react quickly. Emperors come and Emperors go. What matters is the use you make of them for the short while they manage to endure. The Barracks Emperors plays like an abstract game, but let it get under your skin, and it fills you with paranoia, opportunism, malice, and pettiness. I may not be Edward Gibbons, but that sounds about right to me.

Add Comment