Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

Many co-operative games feature a predictably linear progression: showers of bad things and good things—let’s call them cats and dogs—followed by a series of player actions. Rinse and repeat, ad finitum, until the players either survive or die.

On a human level, the real mortal threat to co-operative games, the awkward uncle at the family gathering, is the quarterback—the over-assertive player who talks the whole time, telling everyone what’s best. Not every danger fits in the box. Not every danger plays by the rules.

If I’m being honest, I avoid most co-op games because I constantly fight the urge to take over. That’s right. I’m the uncle. Now, I realize I don’t always know best. I’m actually pretty good at suppressing the impulse to speak. I just prefer making all the decisions. Rather than make everyone dislike me terribly, I stick to competitive games.

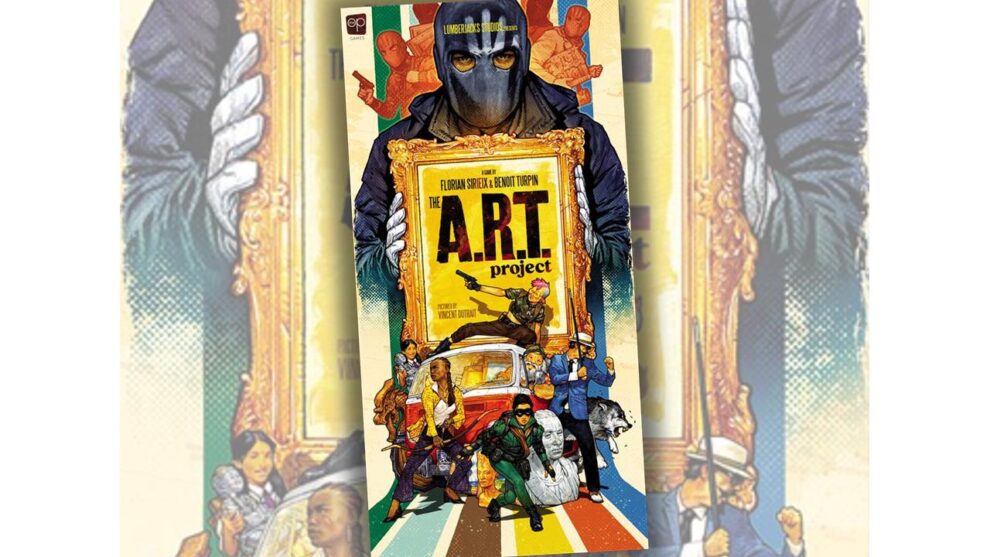

I initially passed on reviewing The A.R.T. Project for that reason, even though I was struck by Vincent Dutrait’s eye-catching cover and the anti-heist premise of the game. The design pedigree of Florian Sirieix and Benoit Turpin wore me down, however, and I decided to give it a shot.

Uncle-proof?

While largely sticking to the co-op script, The A.R.T. Project makes a solid attempt at uncle-proofing the proceedings. Players receive two cards at the beginning of each round that indicate a resource cost, a pox upon the map, and a resulting payout. En route to playing one card each, players may freely discuss the information, with one exception: the cards must remain in hand. In other words, the information flies around the table verbally, never visually.

Players speak and, perhaps more importantly, players must listen—not passively, and certainly not dismissively. The lack of visual organization forces the group to mentally assess a bevy of gifts and gashes and place them in an order of priority before launching the sequence. The sequence is not set in stone, so card choices and player order might change midway through a round. This hampered freedom gives The A.R.T. Project a touch of chaos and a whole load of (loud) personality.

Were the group to lay the cards on the table, the best choice would become crystal clear and the players could rest easy that they did everything possible to win. Relegating dozens of icons’ worth of information to a critical listening exercise, I would argue, is the game. For the sake of fairness, however, I will loosely explain the other rules.

The white glove test

Players become an elite task force interested in recovering stolen masterpieces before “the White Hand” can abscond with the goodies for good. Three resources energize the operation: Fuel for movement, Walkie-talkies to recruit help, and Guns for the shooting. Each scenario utilizes one of six international maps featuring a handful of variously connected locations.

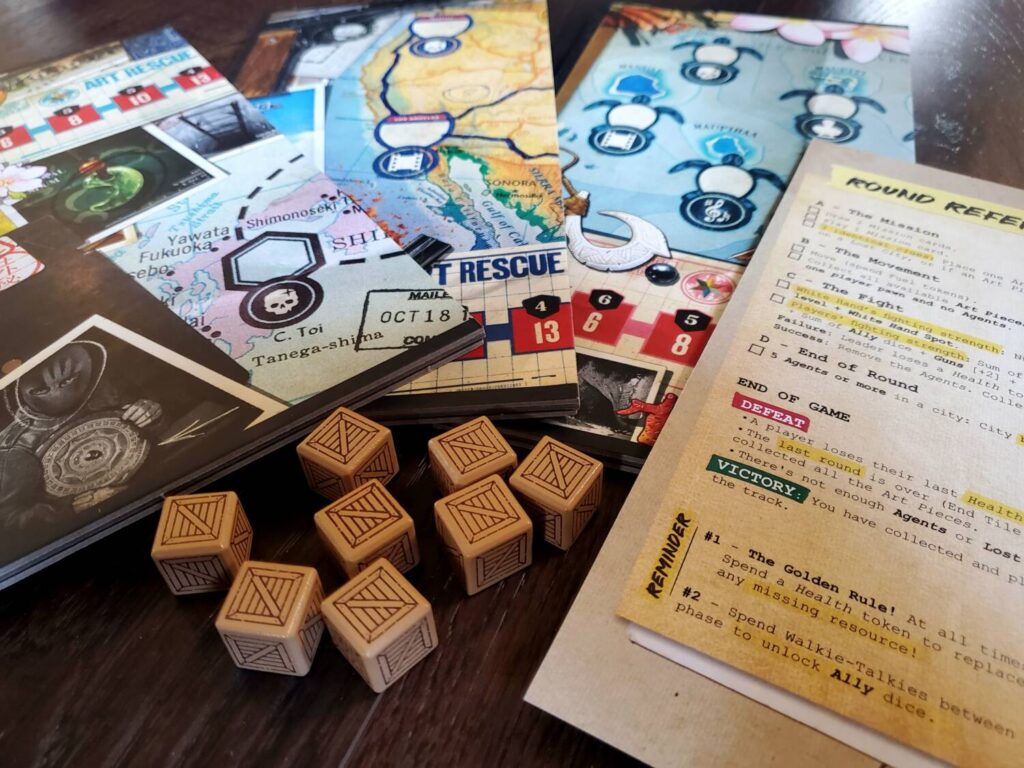

As I said earlier, players choose one of two dealt cards each round, carrying out the actions in order. First, resources are taken away. Then a number of white hand tokens hit the map representing enemy presence. Resources then come back to the team and the card is placed aside face-down. The back of each card bears one or two icons—Clues for the various works of art. As these icons accumulate, they are either spent to re-roll fight dice or forcefully redeemed in threes to place Crates on the map. Crates are the real aim, as players must acquire seven to declare victory.

Once every player has completed their card, players take action, spending resources to move and rolling dice to battle henchpersons. Before or after the action phase, players might spend Walkie-talkies to obtain extra dice—allies in the field—which is good, because the enemy grows progressively stronger throughout. If at any time a player pawn rests in a city with a Crate but no henchfolk, the art is secured. If a round ends with too many henchers in a city, that city is lost for the game.

One final resource is player health. These hearts spend as resources (because enthusiasm is as good as gasoline) and disappear as injuries in botched fights.

If a player dies, the team loses. If too many cities are lost, the team loses. If too many henchies are on the board, the team loses. If the deck runs out, the team loses. But if enough artwork is recovered—huzzah! Victory!

F.I.R.S.T. impressions

I love The A.R.T. Project on the table. The artwork is a spectacular combination of charm and grit, the wooden resource bits and white hands are fantastic, the cards are nice, the “art” crates are sturdy printed dice, the six map boards are honest-to-goodness folding boards. The player van for storing resources is great. Best of all, the player tokens are flattened chess pieces. Adding two frivolous touches: the poster of the box cover is wholly unnecessary but nicely made, but the postcard of the masked White Hand fella lounging on the beach is the right sort of excess. The Op built a solid table presence here.

Adhering to the rules, we began our first mission in Japan. That four-player outing was a stunning (stunned?) victory on the final re-roll of our last-hope turn. We ran around the room in celebration. The Japanese map features easy travel along and across multiple paths, just in case a city or two fall. It’s a flexible scenario to learn the rhythms before every subsequent variation upends the whole operation.

However I’ve yet to win again. Each of the remaining scenarios frustrates movement in various ways and limits player options to boot. Granted, I’ve not had more than one play on any other map. I like to think the odds would turn my way eventually, but there’s no doubting the difficulty. The rhythms of that first game make perfect sense, which makes the pain of each subsequent scenario clear from the outset. We felt like we knew what needed to be done, even if we couldn’t get there. There are challenges in this box, but the challenges are in the play, not in understanding what’s expected. I’d say that’s commendable, even if the game pummels me.

S.E.C.O.N.D. thoughts

I’ve played with two, three, and four players. The four-player outing was dizzying. This card will cost us two guns and put hands in City B and City D, but we’ll receive two fuel and a talkie. Now do that seven more times. What the heck, just go ahead and repeat all eight after that, because there’s no way you really remember what anyone said. The goal is to suss out who will die if their card is played first (yes, this happens more often than is comfortable), whose card will stave off said death, whose card is needed to get a crate on the board, whose card will totally botch the whole crate business, and what, if anything, will be possible once all the cards run their course. Despite the disorientation, we had a blast. There’s no way I want to try six players—I don’t care what the box suggests.

As expected, two- and three-player affairs are less audibly disheveled and maybe a hint more precise. But fewer chess pieces on the map means increased travel to quell disturbances, less of a presence to fight the stream of baddies, and less friends to scoop up crates. The trade-offs make sense. It seems better to have more warm bodies for the map, but the social and mental stress might outweigh the benefits in practice.

If I worry about anything in the game’s balance, it’s whether the cards can really help fewer players to find an advantage. Having those extra bodies on the map means Fuel becomes less important at times since everyone is spread out strategically. Needing less of one resource, ultimately, opens doors to sacrifices that help offset the fact that co-op games are not designed to let you get ahead. Instead, they provide lateral opportunities—robbing Peter to pay Paul, so to speak. Two players will definitely struggle to feel there’s anything they can jettison to get things done. But more players equals more noise. Hmmm.

F.I.N.A.L. verdict

Still, I say The A.R.T. Project works. Easy to teach, easy to learn. The game seems balanced enough to enjoy—challenging, but not (wholly) impossible. Because play depends on dealt cards, it is entirely possible that the deck will be stacked against you. It’s also possible that the deck will serve up victory on a silver platter. But, as I said, the human fun is the communication puzzle. Listening, choosing a card, watching that card play out, and then adapting. Like any enjoyable co-op, the game earns its keep when you’re standing, cracking your knuckles, wide eyed, and, somehow, your jaw hurts. The map is littered with trouble and all you can offer is nervous laughter because you feel like you’re going to die. Regardless of the outcome, it’s over in an hour or less and you can try again.

Winning that first scenario goes a long way to making the rest of the box feel approachable. No amount of visual appeal can overcome a game that feels unnecessarily cruel and unyielding (I’m looking at you, Ghost Stories). Even the losses here have been engaging because we’re sweating through it together. The uncle-proofing measures are unnerving at times, but the audible oddity is a fun twist on the genre. If you’re into co-ops, The A.R.T. Project is a romp worth checking out.

Add Comment