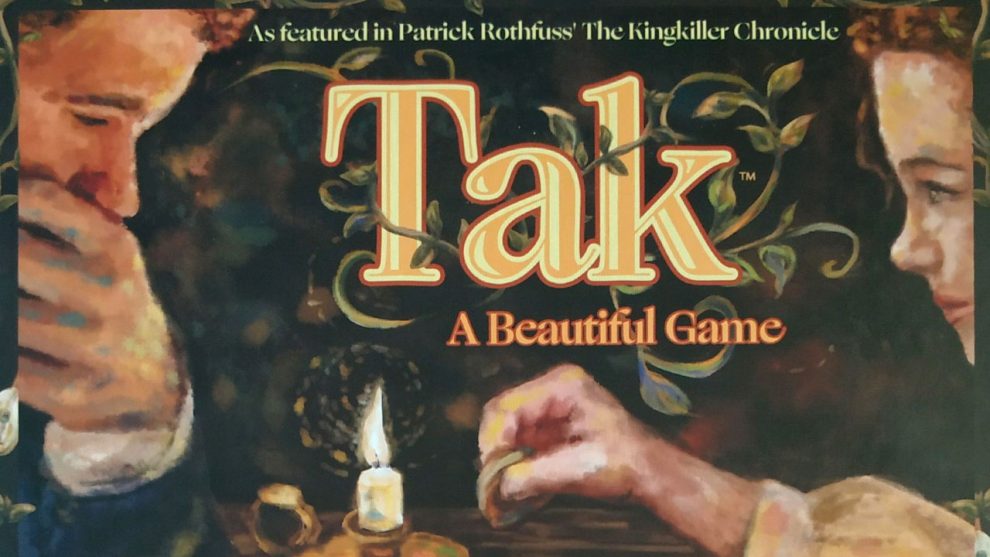

In Pat Rothfuss’ fantasy novel The Wise Man’s Fear, two characters play a game called Tak.

“My next several hours were spent learning how to play tak. Even if I had not been nearly mad with idleness, I would have enjoyed it. Tak is the best sort of game: simple in its rules, complex in its strategy. Bredon beat me handily in all five games we played, but I am proud to say that he never beat me the same way twice.”

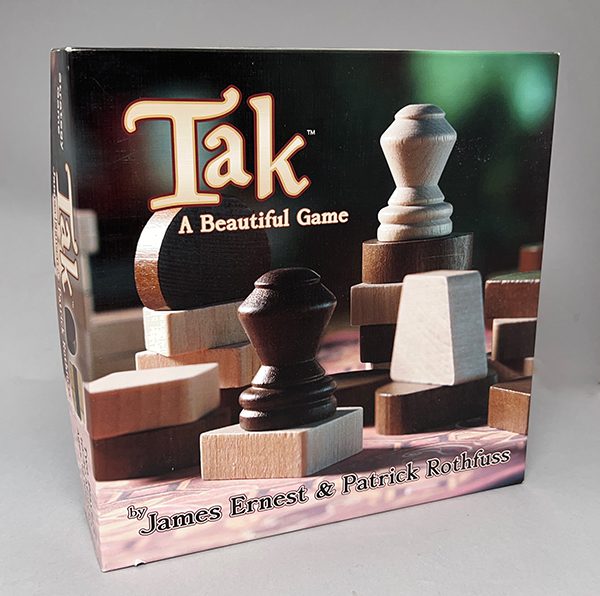

It was from this cursory description that designer James Ernest developed Tak: A Beautiful Game. In 2016 Tak was launched on Kickstarter by Cheapass Games with a goal of $50,000. By the end of the Kickstarter run, over 12,000 people had pledged $1.3 million to back the project.

Tak is a connection game, one where you are trying to link one side of the board to another, usually the opposite side, while working to prevent your opponent from doing the same. While connection games can be enjoyable, modern designers have recognized that the genre benefits from additional options and rules. These additions add layers of complexity to this relatively simple notion.

With Tak, there are two very different winning conditions: (a) create an orthogonally-connected path from any one side of the board to the opposite side or, (b) if all pieces have been placed on the board, have the most pieces placed face up.

Set Up

Before you play, you will need to decide how large you want the playing board to be. You can play on the included board in several ways. On the highly decorated side you can play a 3×3 game by using just the 9 innermost squares. To play a 4×4 game, choose the diamonds at the intersection of those innermost squares. A 5×5 game is played on all the visible squares, while a 6×6 game is played on all the diamonds.

Then take all the number of pieces for one of the two colors as listed in the rule book for the size of board you’ve chosen to play on.

Randomly select a starting player. That person then takes one of their opponent’s pieces (referred to in the game as Stones—which is a bit odd considering they’re all wooden) and places it on any empty spot on the board. The other person then does the same with one of the starting player’s Stones.

And now you’re ready to play.

How to Play

On a player’s turn they may do one of two things. The first is to Place a piece on an empty spot on the board.

There are three types of pieces:

- When a Stone is placed face up, it is considered to be a Flat Stone and contributes to a connecting road.

- When placed on its side, a Stone becomes a Standing Stone, or a Wall, that prevents any road or moving pieces from passing through the square it resides on.

- Your lone Capstone, a unique-looking piece that we’ll get to in a moment.

The second option is to Move one of your pieces, or a stack of pieces that you control.

Moving a piece consists of relocating one of your pieces on the board to any orthogonally-connected square. If the square is open, you can move into it; if the square contains a Flat Stone, (of either color) you may move your piece on top of that stone; if the square contains a stack of Flat Stones, you can move your piece atop the entire stack.

Whoever has their piece on the top of the stack controls the entire stack.

When moving a stack, you must follow the Carry Limit, meaning you can only move the number of pieces at the top of the stack equal to the width of the board. (On a 5×5 board, the Carry Limit is five; on a 6×6 board, the Carry Limit is six, etc.) If the number of pieces in the stack is greater than the Carry Limit, you’ll only be able to move a part of that stack. If the number of pieces is equal to the Carry Limit, you can choose to move the entire stack or a section of the stack.

Stacks must be moved in a straight line. To move more than one space, however, you’ll need to drop one of your pieces on each space as you go. This means if a stack has multiple pieces of your color in the series of pieces, you can quickly create a substantial threat by controlling multiple squares with a single move.

Movement, much like connected roads, is stopped by Standing Stones.

Remember your Capstone? It is perhaps the most powerful piece you have to play. Not only does it count as a connection piece, but it is the only piece that can topple a Standing Stone and lay it flat on the board. As well, no other piece can go on top of a Capstone (including your opponent’s Capstone).

Thoughts

Tak has everything I love in an Abstract Strategy game: it’s easy to teach and learn, yet it quickly shows itself to have surprising depth.

My first few games were about getting a feel for the stacking and moving aspects of the game, while gaining an appreciation for how the different pieces worked together. Later games were about trying to balance finding patterns towards a winning strategy while defending against my opponent’s moves. Admittedly, I don’t do either all that well. But I felt like I should be able to do so, which, I think, is one of the great draws of Tak.

The game has several active online communities that support it and encourage play and discussion. There is an active Tak Talk channel on Discord and the PlayTak web site allows you to play online against humans or various levels of Bots.

While I whole-heartedly recommend Tak as a game, I have issues with what comes in the box for a board game at this price-point. First, the game board is basic cardboard with printed illustrations on both sides. The ‘wooden’ side consists of a dull, cartoony-looking series of wooden tiles. The decorated side has a more pleasing design for the center squares, but the outer edge is a gaudy, flower-and-vine design that is so distracting I’ve never attempted to use it.

If the board was foldable, the box could have been 1/2 the size or smaller. As it is, the box for Tak comes in a respectable second to Splendor for wasted box space.

The wooden pieces come in two different designs (white trapezoids and dark 2/3 circles). These are of good quality, but far too plain for the price. The Capstones look like drawer pulls. All pieces come in simple plastic bags that are not resealable.

The rules for Tak, as well as printable boards of differing sizes, are available at the BGG entry for the game. Consulting your favorite online search engine will provide you with examples of how to make your own boards and pieces. (If Tak appeals to you, consider making your own set. You won’t regret it.)

Is Tak really “A Beautiful Game”? Aesthetically, not in the edition sold to consumers. On gaming merits, however, Tak is definitely a beautiful game.

The better question is, ‘Is Tak worth playing?’ If you’re a fan of abstract strategy games, the answer is a resounding Yes.

As a fan of Tak, I can say that your review is spot on. Thanks!

Thanks. One of my favorite things about the best Abstracts is that they’re both easy to teach and that they generate that, “Ah ha” moment a few moves in as the complexity of the game reveals itself to new players.

Tak definitely has this!

— Tom