Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

For a variety of reasons, you should know going in that this will be a messier review than normal. I don’t think I should apologize, but I feel compelled to warn, at least.

At 1:20 in the morning on Saturday, June 28, 1969, New York City police officers raided the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in the Manhattan neighborhood of Greenwich Village. Such raids were a routine occurrence at the time. There was a script. Patrons were made to line up and produce identification. Female officers took those suspected of “crossdressing” to the bathroom to verify their sex. Alcohol was seized and arrests were made.

For whatever reason, that raid at Stonewall didn’t follow the script. That night, which for all intents and purposes was like any other night, patrons refused to comply, refused to go to the bathroom to be “verified,” refused to produce their IDs. Patrons who weren’t arrested didn’t leave, they gathered out front. This wasn’t planned, it was spontaneous. The gay community had had enough.

By the time the NYPD wagons showed up to take people away, the people outside constituted a crowd. They booed, they chanted, most crucially they questioned. The situation escalated to the point of a riot, an uprising, lasting until 4 in the morning. That night of resistance spun out into weeks of protest, a major turning point in the fight for queer visibility and acceptance. It was then that the fight moved out into the open.

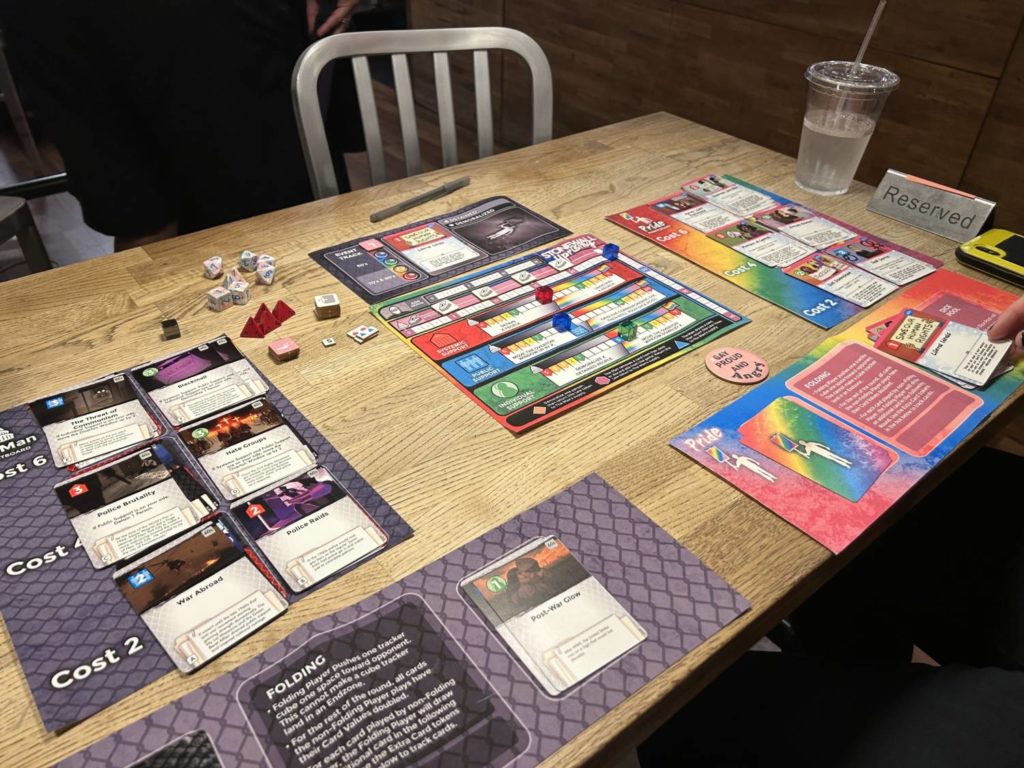

Stonewall Uprising tells the story of that fight across the 1960’s, 70’s, and 80’s. This is a game for two players. One is Pride, the other The Man. Their aims should be clear from their names.

And the Game Played On

Stonewall Uprising is a deck-building game built around a multivalent tug-of-war, as both players work to build Systemic Support, sway Public Support, and gain Individual Support, all in service of their long-term goals. Mechanically, it is almost jarringly straightforward. Each round, you take turns playing a single card from your hand.

As the game progresses into the 1980’s, many cards have additional effects, but the core revolves around moving one of three markers—representing the aforementioned Systemic, Public, and Individual Support—along the corresponding track. There are powerful action spaces at the far ends of each track, and it is in either player’s interest to move the markers as far into their endzone as possible.

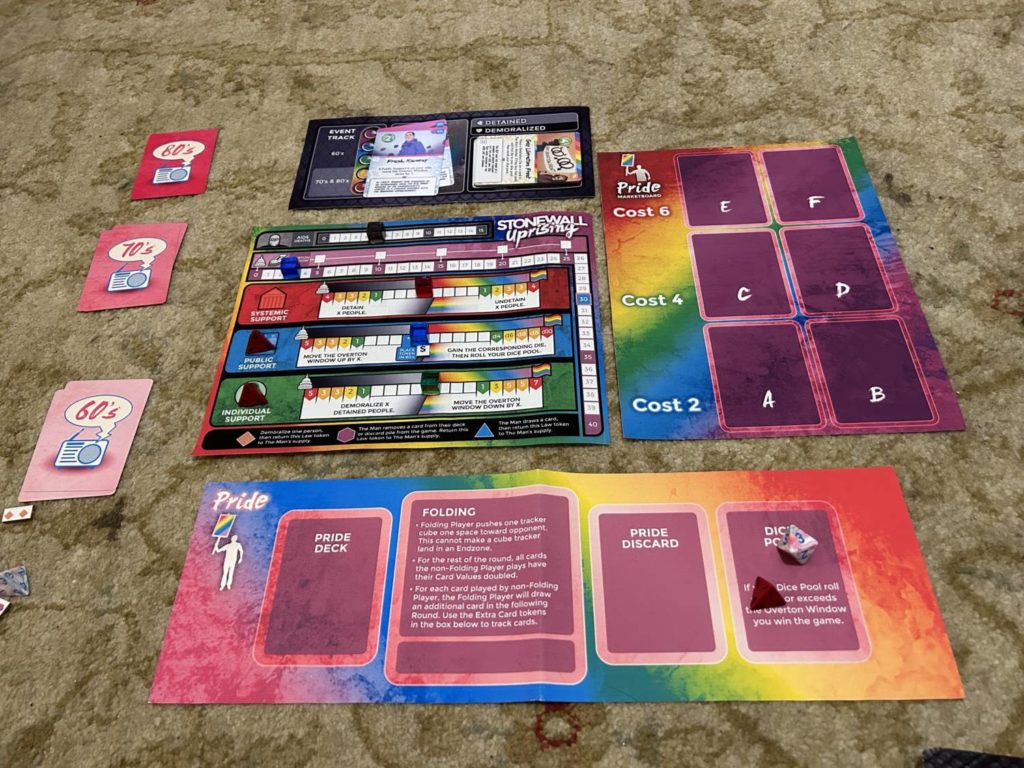

That’s so dry as to almost be boring, but there’s a terrific twist. So long as your opponent is still in the round and you have cards remaining, you can choose to fold. If you do, you’re done for the round. The immediate benefit of folding is that you can use the remaining cards in your hand to purchase new cards for your deck. There’s a little more risk/reward going on here, though.

If you fold, your opponent can continue playing. They can then play as many of their remaining cards as they want, without your interference. Not only that, the value of those cards is doubled. A card that would normally move a marker two spaces will now move it four.

That’s a huge sacrifice for the folder to make, but this sword cuts both ways. For each card your opponent plays after you fold, you get to draw an extra card in the next round. Not only does that mean you will have more options, it also makes it more likely that you’ll have a powerful card to hold onto in case your opponent folds next time.

Folding is a magnificent piece of design work. It exerts tactical and dramatic pressure on both players. I love the design all the more for the fact that designer Taylor Shuss keeps it all pretty simple, allowing this clever twist to drive just about all of the wrinkles in the design space.

The Overton Window

For those who aren’t familiar, the Overton Window refers to the range of policy options that are socially acceptable to the population at large. The growing popularity of universal healthcare is a result of that window shifting in one direction. That Supreme Court Justices didn’t fear people burning their houses down for overturning Roe is also a result of a shift in the Overton Window. Not all shifts are good.

In Stonewall Uprising, Pride wins through a combination of two things. First, by marshaling sufficient individual support to move the Overton Window track to the left, lowering its point value. Simultaneously, Pride has to sway Public Support in order to gain acceptance. The amount of acceptance Pride has is represented by a slowly-increasing pool of dice, rolled en masse each time Pride acquires an additional die. Should the total of those dice ever meet or exceed the current value of the Overton Window, Pride wins.

This is thematically iron-clad. It’s incredible work, and accurately captures the way those dynamics shift in the real world. As a gameplay mechanic, though, I find it lacking. The arbitrariness of a die roll meeting an ever-shifting number doesn’t feel dramatically satisfying. My only criticism of this game after five plays is that the ending itself has yet to feel any particular way. There’s tension, there’s loads of it, and suddenly that tension deflates.

The AIDS Crisis and Other Difficulties

The premise of Stonewall Uprising has met the same response every time I’ve discussed it. When told that the game concerns the fight for gay civil rights, everyone says “Wait, does that mean one player is the oppressor?” Whether the person I’m talking to is queer or not, it makes no difference. The immediacy of the discomfort is evident every time.

Compare this with general responses to Votes for Women, about the fight for women’s suffrage. With that game, the observation that one player has to work as the Opposition, the fight against giving women the right to vote, is continually met with a chuckle. Not so with The Man, Uprising’s representation of entrenched power structures. Despite being close cousins, only The Man is consistently met with unease, and a good percentage of people have outright said that they would not be willing to play that side.

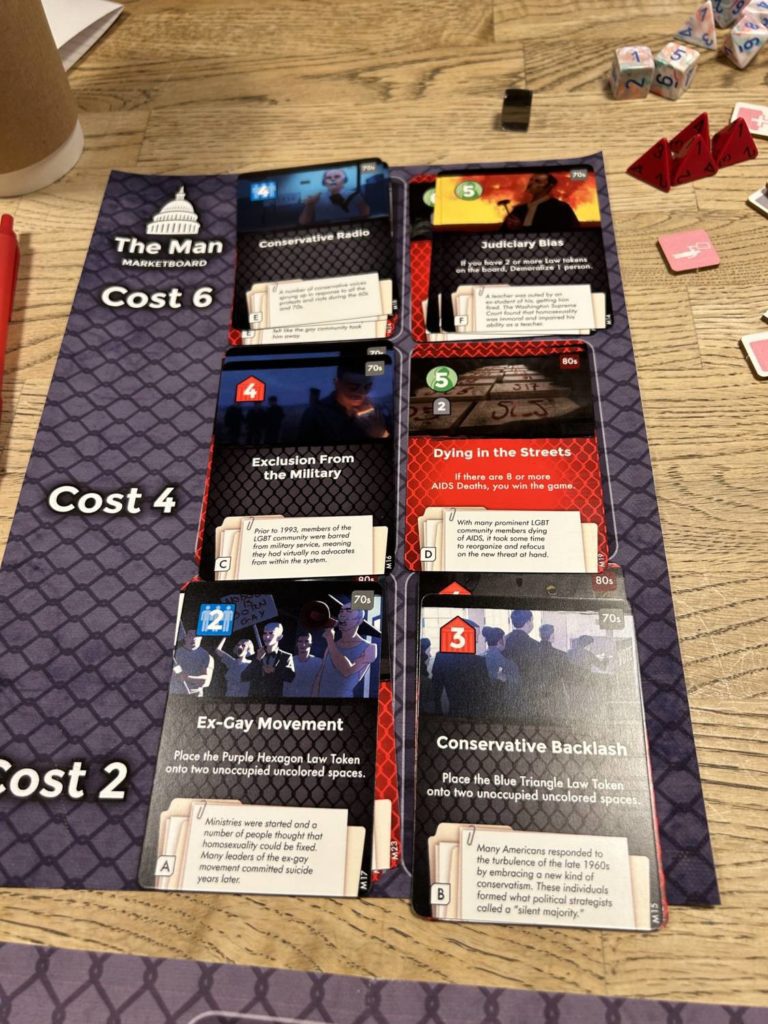

I can’t quite square the difference in response, despite feeling it myself. It’s not anything Shuss has done. His editorial stance on all this is unambiguous in every facet of the design and production. While Pride’s cards are full of inviting colors, The Man is dour, even terrifying. Whatever is happening, is happening on a conceptual level. It could be that we feel further from the 19th amendment being under threat. I’m not sure we’re as right about that as we’d like to be.

Once Stonewall reaches the 1980’s, things take a crushing turn. There is a fifth track, the AIDS Deaths track, which activates in that decade. It is brutal, and emotionally exhausting. It is in The Man’s interest to rack up AIDS deaths. If he—I apologize, I generally use “they” for player pronouns, but in this case I cannot square the circle of “The Man” and “they,” and somehow “he” feels right—allows enough people to die of AIDS, he can so fully stigmatize the queer community that he wins the game.

This is difficult. It is always difficult. If you’re going to make a game out of this, it should be difficult. There is something of the sin eater about the player who takes on the role of The Man. It is wrenching to buy a card and then catch yourself taking abstracted joy in the fact that it increases your chances of winning by non-abstractedly allowing people to die. Stonewall Uprising is not a game for everyone, particularly in its later stages. I’m not even sure it’s for me, and I think it’s excellent.

I spend the 1980’s portion of the game thinking about Ben McFall, who I was lucky enough to count as a friend while working at The Strand bookstore in Manhattan. During a lunch break, Ben, who was about 70 at the time, told me stories about what The Strand was like during the peak of the AIDS epidemic. “I remember, there was one young man who worked on the second floor. I saw him get out of a cab just a block up from the store to get to work, that’s when I knew.” AIDS had rendered his coworker too weak to take the subway, so he took a cab, hoping to hide it from everyone. I’ve never been able to shake that. “That’s when I knew.”

We Shall Overcome

The manual states explicitly that Pride can only be delayed, never defeated. Even if The Man wins this game, Pride’s victory will come just around the corner. Still, if you want to play Stonewall Uprising without putting anyone in the position of being The Man, it includes a solo mode. The game’s POV and angle are reinforced by the fact that there is no solo mode for The Man. You cannot sit down for a pleasant afternoon’s oppressing. If you play this alone, you will play as Pride. As it should be.

The solo mode is well-designed. Not only is it simple to learn and execute, it puts up a good fight. I readily lost my first game to the bot, and just managed to scrape out a victory in my second. I wouldn’t say the bot plays well, though. I won my second game because the bot folded according to its automatic conditions for doing so. If a human had folded at that point, it would have been a massive misplay.

On the night of the original Stonewall uprising, when the police sent in the Tactical Patrol Force (at the time, believe it or not, the NYPD had but one elite strike force), the crowd responded in part by forming impromptu kick lines. That’s how we win. You meet their cruelty and small-mindedness and violence with joy, with love for one another, and, when the situation calls for it, a brick.

Add Comment