Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

At this stage, I will essentially review anything published by Capstone Games. Clay Ross and his extended network consistently pull in gems that have a certain kind of buzz for the Eurogame design elements I love. Between the “Iron Rail” series of cube rails games, the Terra Mystica family of products, and a little-known zoo simulation game called Ark Nova, Capstone has gotten it right much more often than other publishers.

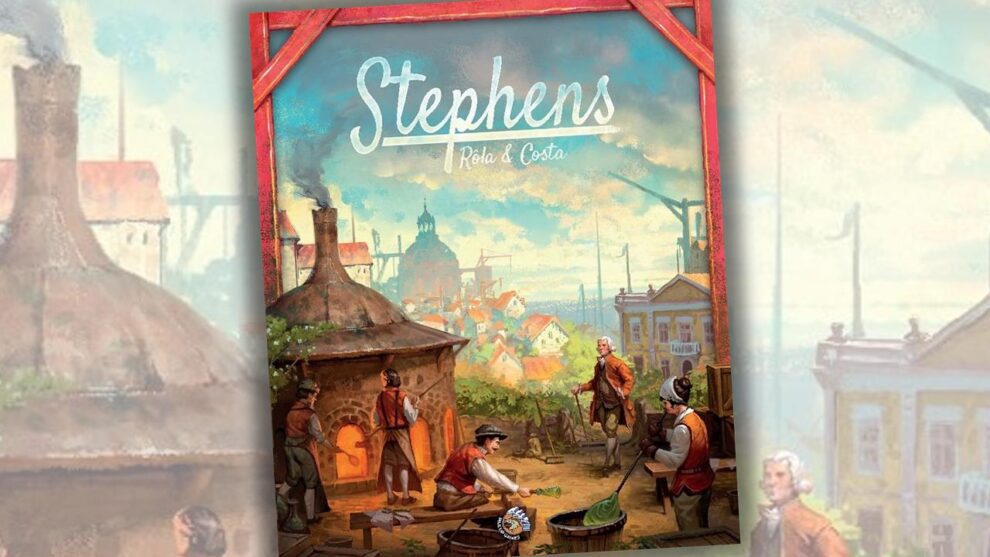

Stephens (a 2024 release designed by the Portuguese design duo known as Costa & Rȏla) is the latest in a long line of medium-weight Euros with a handsome production, a relatively low playtime, and a simple turn structure and cardboard money chits. (I used the included money for the first of my three review plays before pivoting to poker chips.) It has a novel reset/clean-up system that, in the right hands, leads to snappy play and lots of chances to gather income that will be used to further other in-game goals.

In the wrong hands, this system leads to one of the few problems a Euro design can possess—the ability to actually do everything a game has to offer. Many of these games push hard on finding an ending that ensures that players have the chance to only do some, maybe most, of a game’s elements, but never let you see what it might be like to unlock everything, or max out multiple areas of the design.

Players control the pace of play in Stephens, and in one of my games, I saw the downside of that process. Stephens could use another guardrail or two to speed up play when the table begins to stall.

Glass, Baby!

Stephens is a 1-4 player economic set collection and order fulfillment game that should play in about 90 minutes, ideally less, depending on player count. I did three plays for this review—once solo, twice at four players, with each of those multiplayer games done with different gaming groups. While the solo is easy to administer and has a number of ways to spice up the challenge level, I had more fun with the full player count sessions of the game.

Stephens asks players to take on the role of entrepreneurial master glassmakers in 1769. A foreign businessman named William Stephens has decided to open operations in Portugal, and with the help of both local and immigrant glassmakers, you’ll produce glass at the “famous” Stephens Factory. Players must also invest in local businesses while acquiring contracts to fulfill the needs of partners around the world. The clock is ticking: the French army is coming, and the game ends when at least one player’s score marker crosses paths with a neutral marker tracking the progress of the French forces.

Stephens features a very straightforward action system. You only have two choices on a turn. You can take a cube from an action space to trigger the action of that space—keeping that cube to fulfill contracts or pay for other game elements—or you can place a disc from your personal player board on a profession card to become either a master or apprentice of a certain skill. These professions are the only way to earn in-round income, because the profession cards are aligned with six of the game’s eight action spaces. If any player takes a cube from an action space in a row with a profession card, all players with a disc on a card in that row get a chance to trigger all of their cards there.

This leads to a fantastic amount of interaction, along with a wide array of table talk as players jockey to have their rows activated. “Come on, Joel…you KNOW you wanna take the blue cube from that factory space!!” This also means that everyone is pushing to align with some of the better action areas by having cards in the right spots to provide a nice economy drip all game long.

The other thing with the profession cards: they must be built in a way that ensures a proper balance between rows. The bottom rows of profession cards must be larger than the rows above them. The bottom rows are also worth the fewest amount of points, which leads to a consistently entertaining game of chicken as players try to swoop in and legally build profession cards on higher levels, which are worth a lot more points during end-game scoring. (In each of my plays, this scoring element has proven the most consequential, which I think hurts the game. We’ll come back to this.)

The discs placed on those profession cards also offer a fun puzzle—each disc removed from a player’s mat and placed on a profession card unlocks a new ability for that player. Some let a player remove more cubes from small factory spaces. Others grant a discount when buying contracts, while one bonus lets a player wipe the cards from a profession card market row before shopping for better options.

But each player gets to choose the order in which they unlock these powers. I enjoyed having the freedom, although some of the options (unlocking end-game scoring bonuses in the early rounds seems like a fail, and will I really need to have a chance to buy two contracts in a single action when I never have any money or spendable influence?) didn’t strike any player’s interest during my multiplayer games. Almost everyone goes for the power that allows a player to break the rules around profession card placement early on, and the ability to score one point during each reset phase also felt like a gimme for an early-round unlockable power.

So, there’s freedom around this process, but the choices seemed a bit more guided than the rules initially let on.

The Stall Game

Stephens has a nice push-pull with its action system. And when two of the four areas in the large factory area of the board are out of cubes, a reset phase kicks in where players produce a river of resources that are then placed to trigger income as well as other actions that can give a savvy player who plans well a leg up.

On most turns, players are usually doing something, particularly late in the game when players have one or two profession cards in every row. I love the lack of downtime here, and if games keep moving, you might be looking at a three-player game that might wrap up in an hour, with plenty of interesting minor decisions to keep the action humming.

But. BUT. In my final review play, the players all found themselves wondering when the game was going to end. Three of the four players had placed all of the discs from their player boards on cards. Only two of the 50 profession cards were left in the market. Two players had the maximum of 25 influence, which was going to score 25 points for each player, based on an unlockable power tied to boosting scores. Two players had three full columns of contracts (i.e., a lot). One player had maxed out a central, two-tier scoring track tied to the use of payment for natural resources which would award 30 more points.

The game only moves forward when players take cubes from the large factory spaces. If players don’t select these cubes—and there are easy ways to avoid that—the game grinds almost totally to a halt as players max out their income. They might exhaust all of the Accessory tiles, used for a separate set collection element of both contract and end-game scoring. In one of both the best and worst elements of the design, players can continue to take investment and/or contract cards if the factory that triggers that action is out of cubes, as long as they have unlocked a certain power on their player board.

In that final game, our playtime edged just over two hours before we got to final scoring, and the final scoring is mathy, people. Stephens can badly outstay its welcome when players drag out the game-end triggers. I don’t know if players have found a lot of ways to overtake a runaway leader by stalling this way, but it’s possible. Your mileage may vary on how this makes the table feel as everyone sits around maxing out their mat.

But when the game is in motion, particularly the early and medium stages of play, Stephens is fantastic. With driven players, I think Stephens might work best as a two- or three-player game based on what I have seen at four players. I love the race to get the best profession cards, and figuring out a way to run a sustainable production engine that both scores points and doesn’t break the bank was crucial in determining the winner in my plays. Final scoring is a bear to compute but it all makes sense, so the chore comes mainly from spending a lot of time counting up all the ways players can score.

As a production, I really appreciated the player mats and the recessed spaces for the discs. It’s also easy to tell from across a large table what powers each player has access to, as you plan around the ways an opponent may or may not snake your next action.

Two negatives popped up, in terms of look and feel. First, one of the colorblind players in our group complained heartily about how hard it was to differentiate the orange and pink colors on the contract cards, and even I had to admit that the colors were a bit too close, even for someone who could pick out the colors more clearly. The second one: why the heck are the numbers that dictate requirements for the reset phase refills so tiny? Players who are not sight-challenged found themselves lurking directly over the board to see the numbers…for the life of me, I can’t figure out why a board so large needed to print these numbers with such a small font.

(Speaking of the board: you are going to need a surprisingly large amount of space to accommodate the board, player mats, and the profession cards that build off either side. We joked that players could only add a profession card if it could fit on the table…and I have a pretty large table!)

Stephens was interesting. I’m not sure it will survive continued plays before we move on; it feels like some areas are an easier path to high scores, such as unlocking the scoring bonus for influence (much easier to score 25 points there than other categories) or placing profession cards on the third and highest rows (five points each, versus one or three points for lower levels). Contracts with two, ideally three, cubes are so much more valuable than contracts showing only one cube, so there’s always a fight for the same cards, even three plays into my experience.

But that’s a problem for another day. Stephens provided a lot of fun decisions in my first few plays and I really enjoyed many elements of this design. I don’t know the other games Costa & Rȏla have designed, but now I’m going to find out!

Add Comment