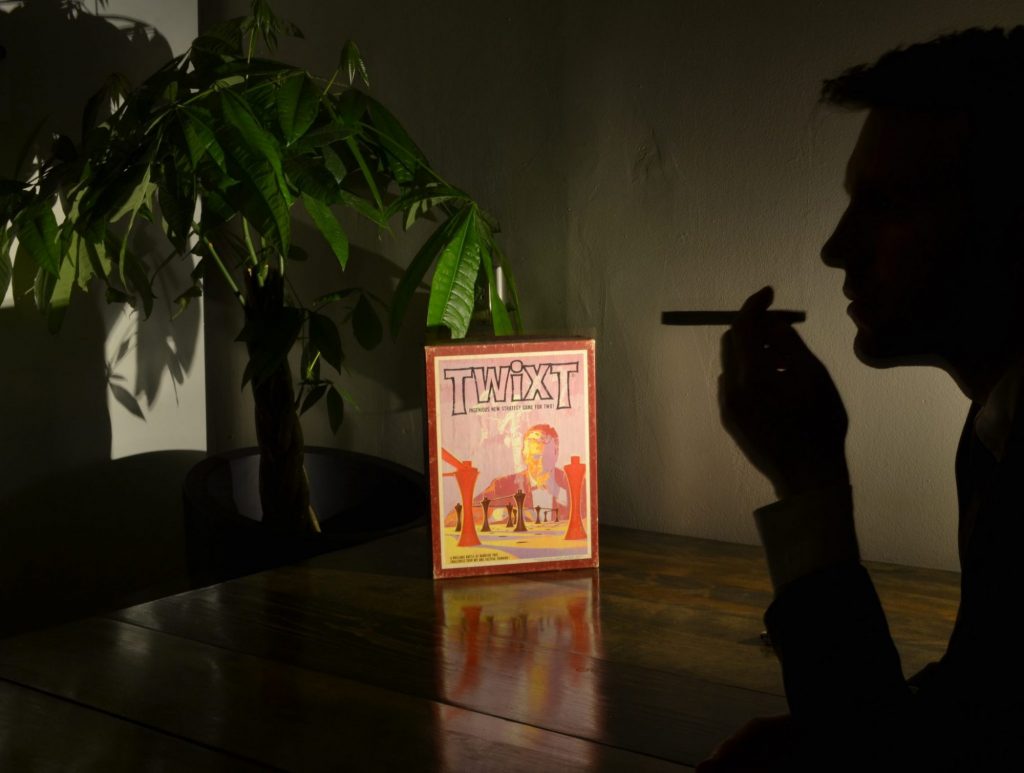

Throughout the sixties and seventies, abstract strategy games had a very particular way of marketing themselves. Thumb through a few dusty boxes and you’ll see a trend emerge: moody lighting. High concept furniture. Thoughtful men frowning at cardboard. It was all an appeal to some grand idea of sophistication: this is a smart game, played by smart people (which, perhaps, could include you). This was the era in which Reversi was re-named Othello, in the hopes of riding Shakespearean prestige. This was the era in which Chess was important enough to stand in as a skirmish for the Cold War. You can’t get much more serious than that.

These days, board game ads appealing to the “refined” are few and far between. For this, I’m grateful— you can only hear so many comparisons to Chess before your eyes start to glaze over. People aren’t afraid to play something colourful, and they don’t need a marketing blurb to know that games matter.

Looking back, you can’t help but wonder: how many of these abstract strategy games were smart enough to merit the grand words used to describe them? And how clever would a game have to be to deserve the marketing strategy of a luxury car commercial?

Squadro is a smart, sleek game. A game so clever that it might just — maybe — deserve some of that old-school cigars-and-space-race marketing.

Rules of Play

Like many of its contemporaries, Squadro’s rules are simple enough to explain in a few sentences, but smart enough to hide a lot of careful choices going on behind the scenes.

In Squadro, two players are racing to cross the board and then get home again. One player moves their pieces in a straight line horizontally, while the other player only moves perpendicular to them. All of your pieces exist on a single axis of movement: while the game is played in two dimensions, each piece only ever moves in one.

Each piece moves an amount of spaces shown by the dots beside its starting slot. Every turn, a player chooses one of their five pieces and moves it forward. If that piece reaches the edge of the board, it turns around, and will move the opposite direction on future turns (in the hopes of getting back home).

If a player gets four of their five pieces home, they win.

There are a few clever tricks here that make Squadro the tense game of tactical negotiation that it is. The first is what happens when a piece crosses paths with an opponent piece.

If your piece is supposed to land on or pass over one or more opponent pieces, it passes over, then lands on the next available space. The opponent piece (or pieces) is then sent back to whatever side it just came from. Sometimes that’s okay. Sometimes it hurts.

This is because Squadro has a twist that makes rushing difficult. Each player has some pieces that move a single space per turn. They also have pieces that can jaunt along at three spaces a pop. When either of these pieces reaches the end of the board, their movement speed is flipped. Coming back home, that three space sprinter is now crawling along at one space a turn (oof). On the other hand, if you managed to get a single-spacer all the way to the end, now it can bolt back home at three spaces a turn.

This means that players are constantly trying to position their pieces to minimize losses, all while threatening their opponent’s pieces with some clever positioning. The game quickly becomes a stand-off. Since you can’t pass on your turn, this is an impasse that someone will be forced to break — whether they want to or not.

Playing with Feelings

In an abstract strategy game so much of what matters is the feeling of play. Some games are a quiet summation of small movements towards a distant end. Other games are immediately oppositional— first to come to mind is 2008’s Push Fight, so ferociously tight that Logan Giannini once referred to it as “a judo match held in a closet”.

Squadro strikes a comfortable middle ground, neither leaving players crushed with tension nor aimlessly unsure what to do next. A piece being jumped is not a misplay in this game, and you’re bound to have a good shake of your pieces sent back to where they came from by the time the game is over. So much of the decision space for Squadro is weighing whether those losses are acceptable or if they will cost you the game. Which move sacrifices the least? Can I threaten one of her pieces at the same time?

There’s something to be said for the game’s pacing. Not only does every move feel like it means something, the game also knows when to call it quits. To win, you only need four out of your five pieces to get home. This neatly solves the problem of what would otherwise be an obvious last few moves. It also means that on your turn, you always have some kind of choice to make: no player is ever left with a single piece and a story that’s already been written.

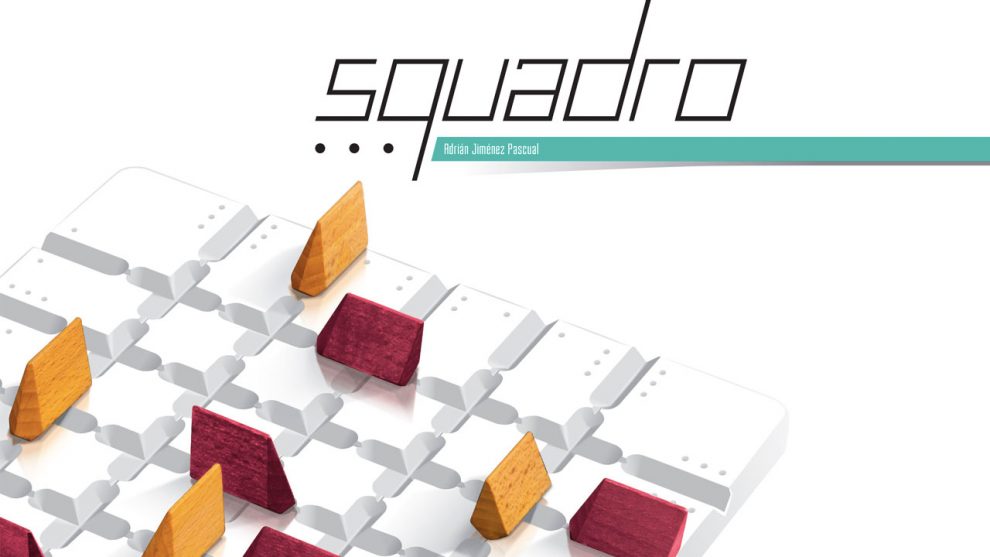

A Word on Aesthetics

Because I don’t think I’ve said it yet, here it goes: Squadro is totally gorgeous. The chiseled wooden pieces stand up in perfect little slots, clearly facing the direction they need to go.

The board is a thick slab with custom indents for its pieces. It’s actually heavy.

Neither of these things are in any way necessary: the board could be a slim paper mat, player pieces represented by punched-out cardboard arrows.

But they’re not. And I have to admit, it’s really, really nice to look at. I like to think I’m not overly swayed by aesthetics… but in the world of abstract games, it doesn’t hurt to stand out a little bit. All you’re running on is the bare-bone rules and the quality of your materials. Squadro would still be a good game without these things, but it sure is easier to convince someone to play something as sleek as this is.

Closing Thoughts

There are a lot of abstract strategy games out there, from Chess reboots to funky new ideas. For one to get my seal of approval, it really has to do three things:

- Make me think.

- Make some choices hurt.

- Do something a little differently.

I think Squadro does all of this. Making an innovative design in a well-trodden space is challenging, and Squadro has accomplished this in a very unusual way: by making players think on a single axis of movement. Every clever design decision in this game unfurls from that one central tenet, and I love what freshman designer Adrián Jiménez Pascual has done with it.

If you like abstract strategy and you’re looking for something new, give Squadro a try. It’s earned its place in my library, and I can’t wait to bring it outside for patio season. The wind doesn’t stand a chance against this one.

Author’s note: A copy of Squadro was provided to Meeple Mountain for review purposes, but my opinions are my own.

Add Comment