Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

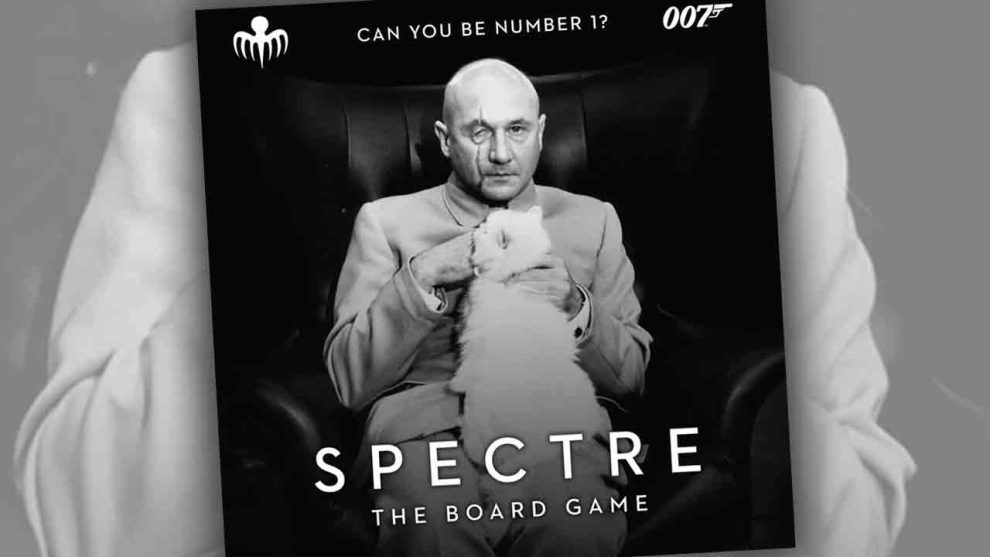

The Special Executive for Counter-Intelligence, Terrorism, Revenge, Extortion (SPECTRE) is the perennial thorn in 007’s side—so long as the rights to the criminal organization aren’t enmeshed in intellectual property disputes, that is. SPECTRE was certainly the thorn in Sean Connery’s side, and eventually became the thorn in Daniel Craig’s rebooted side. The fifty years in between are more legally tenuous, though Roger Moore had a direct run-in as well.

I cannot imagine the depth of struggle and cost involved in obtaining permissions for the characters and film imagery surrounding SPECTRE: The Board Game. Yet here they are. Modiphius Entertainment (Thunderbirds, Agatha Christie: Death on the Cards) has teamed up with Kaedama, the design team that includes Antoine Bauza, Corentin Lebrat, Ludovic Maublanc, and Théo Rivière (Draftosaurus) to unleash the Bond baddies.

SPECTRE puts players in the role of iconic villains from the James Bond franchise as they compete to become Number One in the notorious organization. As part of a singular evil entity, they must occasionally work together and avoid 007, who is always in the way, but when the last chip falls, there can be only one victor.

“World domination. The same old dream.”

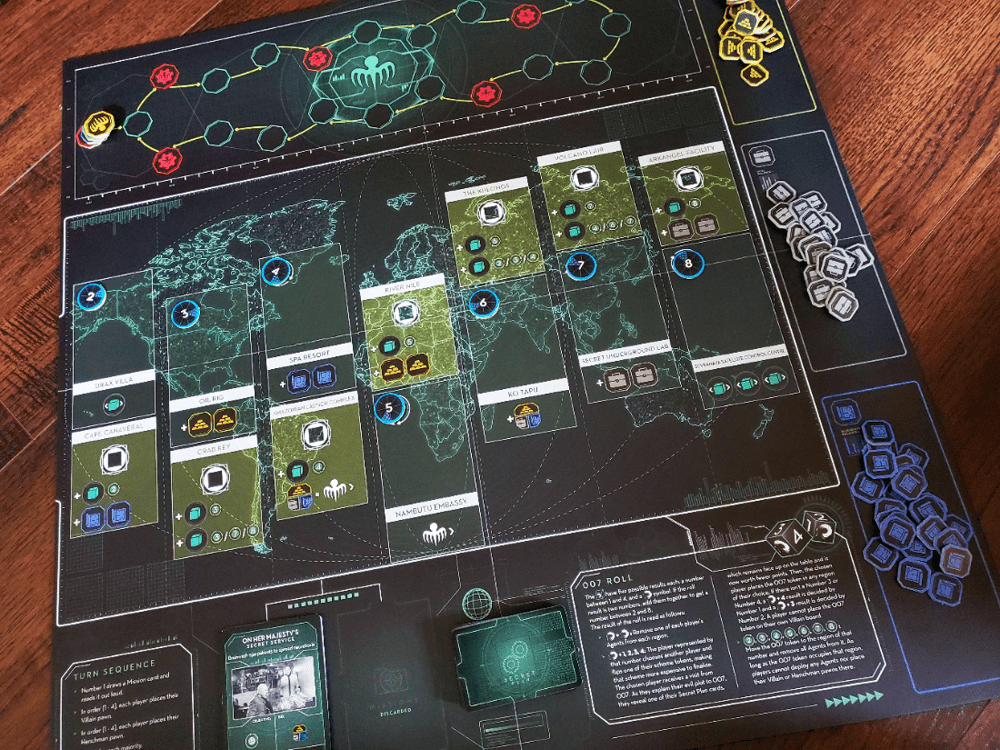

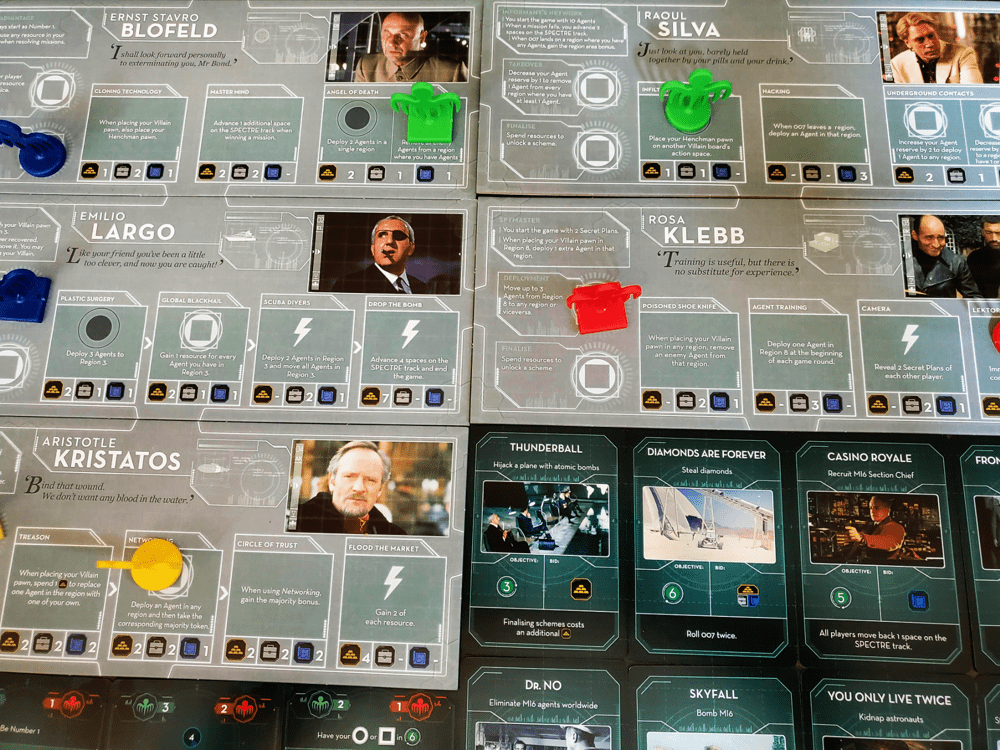

The dominant feature of the SPECTRE board is a world map broken into seven regions. Atop the map, the SPECTRE Track is a constant reminder of the competition at hand as players race their token along. Players take the role of a specific villain, complete with unique abilities and four character-specific Schemes for world domination on individual Player Boards.

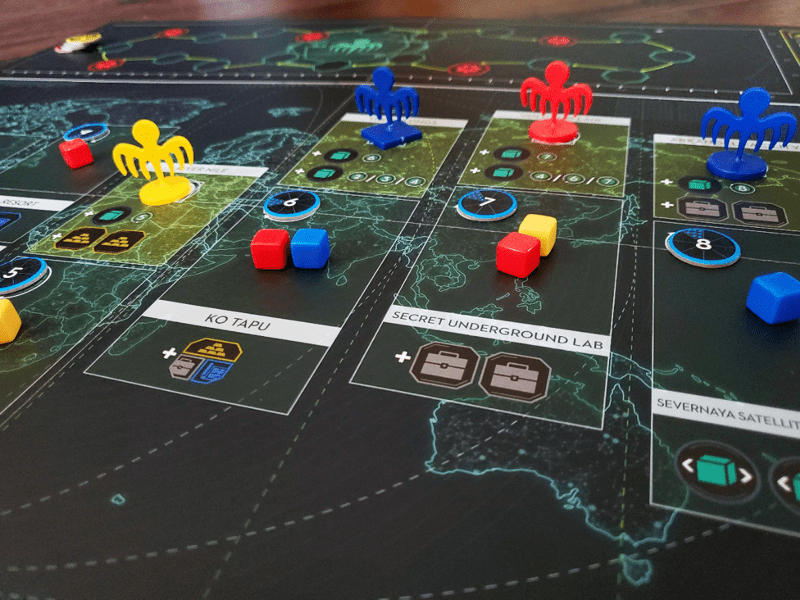

The progression of play in SPECTRE is anything but rhythmic as several mechanics blend to move the story. In each round, players have two turns, first to place their Villain pawn, then their Henchman pawn. Each of the map’s seven regions contains a space. Each player board also contains anywhere from two to five possible spaces.

When placing pawns on the map, players also place an Agent cube and receive a bonus of some sort, either resources, extra agents, or potential movement up the SPECTRE Track. The heart of the game’s decision space revolves around this map. Controlling each of the areas grants a bonus at the end of each round and opens the doors to completing Secret Plans. (More on those in a moment)

When placing pawns on the player board, each of the five Villains has their own areas of expertise and advantage. One space on every player board, titled Finalise, allows players to unlock their Scheme spaces with the right resources. Scheme spaces might open up a new action or an ongoing ability.

After placing two pawns and any corresponding Agents, players evaluate the seven regions to determine which Villain takes hold of the majority token, after which the bonuses flow.

Each round, players have their eyes on a slightly more confusing and cooperative Objective card. Players could work together to achieve this Objective—placing pawns in specific regions, possibly on the card itself (wasting a turn), or simply obtaining the right combination of resources. Players receive Mission points for each sacrificed pawn, placed Agent, or surrendered resource, the latter of which is given in the form of a Bid.

Bidding is essentially a bribe to SPECTRE of Gold, Intelligence, and/or Blueprints, the game’s three resources. Players may discuss the Bid, but ultimately decide privately how many resources to contribute. Success comes by reaching a number of Mission points determined by the player count. If players successfully achieve the Objective, they avoid a penalty. If they fail, some effect befalls the entire table.

In the case of success, the player who achieved the highest total of Mission points receives two added bonuses—moving up one space on the coveted SPECTRE Track and the ability to resolve a Secret Plan card.

Throughout the game, players receive these Secret Plan cards as private goals when they succeed in an Objective. Most involve a circumstance—hold the majority token from Region 5 and have two Agents in Region 6, for example. Some might be an additional bribe. Some might require a specific number of majorities. The winner of an Objective—the one with the most Mission points—may complete a card, if possible, to move up a number of additional spaces on the SPECTRE Track. These cards often require a keen sense of timing and an impeccable amount of forethought, though the endgame is an open season opportunity to complete these cards en masse.

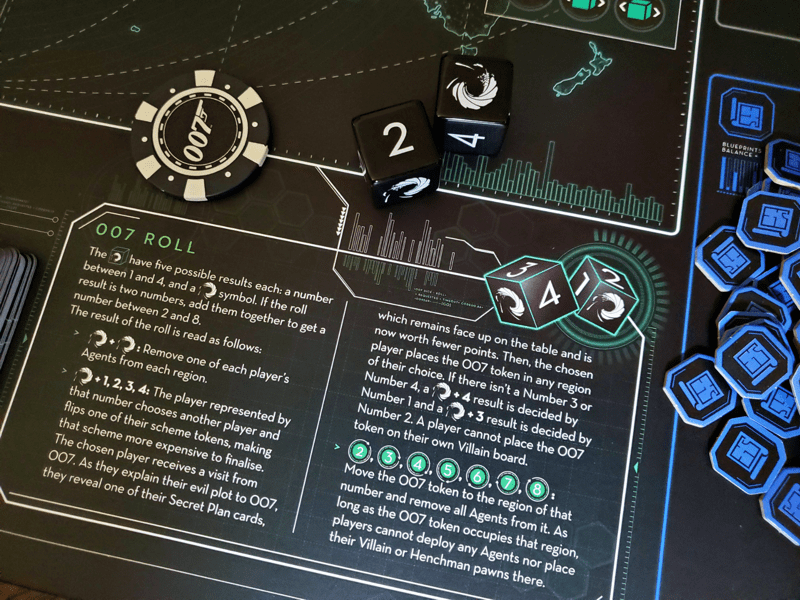

Players then set 007 loose on the map by rolling two dice that feature the numbers one through four and two familiar Bond symbols. Based on these symbols, one of three things will happen. Bond, and his best-component-in-the-game poker chip, might land in a Region of the map, emptying it of all Agents. He might stay off the map, but with his behind-the-scenes work he causes each Villain to remove one Agent from every Region on the map if possible.

Finally, 007 might be “gifted” to one Villain who then chooses to unleash him on another player board. This unpleasant maneuver means one of the Villain’s Schemes will become more expensive to unlock, plus one Secret Plan card must be revealed. Apparently Mr Bond knows how to make them talk. The chosen player, though, gets a shot at insta-vengeance by deciding where Bond will land on the map.

Once Bond has worked his annoying charm, players reclaim their pawns and determine who is the current Number One. Throughout the game, players have placards in front of them representing Numbers One through Four. These placards change places from round to round according to the SPECTRE track. Each placard grants a particular ability for the round. A new Objective card comes to the light and players prepare for another round of play.

On that SPECTRE track there are several red spaces bearing the familiar spider icon. Landing on or crossing these spaces grants the Villain a free action from their personal board, provided the action has been unlocked if it is part of a Scheme. This includes the Finalise action, meaning players might expand their capacity during these bonus moves.

“I do not like failure.”

I understand I’ve included a deep dose of rules for a review. But here I felt it necessary to be expansive because the rulebook for SPECTRE: The Board Game is, in a word, broken. In fact, I’m still not sure I’m playing entirely right after five or six games because there is so little conversation available at this point to supplement the pages that read about as clear as wax paper. It is the sort of rulebook that helps much more after you’ve played the game once or twice. Of course, that means playing at least one time in the dark… while wearing sunglasses. I just want to help folks along who are aiming to learn.

I’m sure there are translation issues in the book. But I’m also sure it’s poorly organized and utterly useless as an in-game reference. It is the sort of book that requires reading entire pages without interruption. No answers at a glance here, folks!

The order of operations for each round is printed on the board, which is helpful. The devil here, though, is in the details. There are numerous sub-points that raise sequencing questions. For example, when the round ends in Objective victory, players must determine a winner. Somewhere in there everyone receives a Secret Plan. Somewhere in there the winner is able to complete a Secret Plan. Somewhere in there the winner moves up on the SPECTRE Track, which may or may not trigger an action from their Villain board, which may or may not alter several realities on the board, including the number of spaces to move on the SPECTRE Track. Ditto for the endgame, which raises all sorts of questions as well.

I cannot stress enough the frustration I feel regarding the rulebook.

“That’s a Dom Perignon ‘55. It would be a pity to break it.”

Here’s the real rub when it comes to my frustrations with the rules: This is a good game. At least, I would call it a good game according to my current understanding.

The whole business of controlling the map of the world is wonderful in its simplicity. Place a pawn and an Agent, then take the bonus. It’s simple, but there is a load of fun in the decision, especially as the game wears on. Early on, players battle to unlock the right combination of abilities. But because the endgame includes a bevy of Secret Plans, the final rounds run rife with tension as players vie for control of specific majorities, specific spaces on the board, and specific resources. It’s a definite highlight.

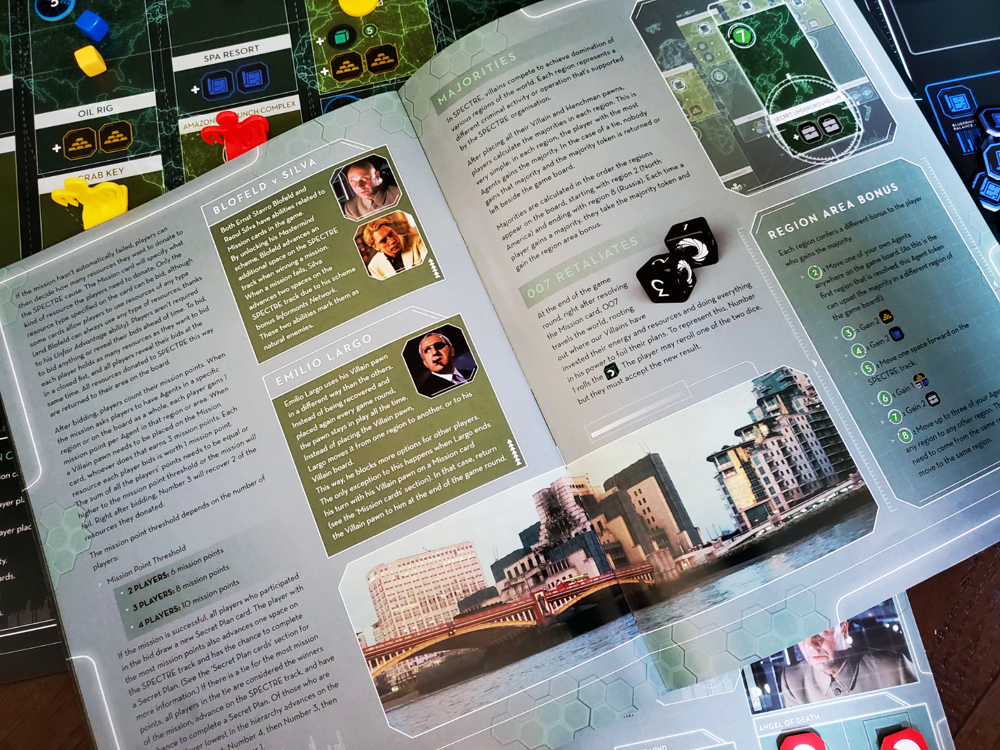

Personally, I enjoy the frustrating stress of semi-cooperation in the Objectives. The reasons for cooperation wax and wane for various players depending on the looming penalty. There is always a reason to help, but sometimes the reason to obstruct is equally taut, especially if you are Raoul Silva. Silva is the game’s monkey wrench here because he doesn’t want the group to succeed. He moves up on the SPECTRE Track by failure. At the same time, if he doesn’t participate at all in the Bid, he receives no Secret Plan card in the event of success. You never know what you’re getting with that guy. He might toss in a resource to get the card. Then again, he might not. It’s quite beautiful. If the group can’t cooperate to neutralize Mr Silva, he will run away with the victory.

Ernst Bloefeld can spend any resource as if it were wild, and he could potentially move TWO spaces as the winner of the Objective. He is a direct counterpart to Silva and the sort of guy nobody really wants to cooperate with—yet they must. Those are the sorts of decisions that keep SPECTRE interesting. Rosa Klebb is a genius for controlling the map via her love of the easternmost eighth Region. Emilio Largo is the only player with a private Scheme to end the game early. Aristotle Kristatos has a nose for getting what he wants out of the map and those resources, presumably, mean more successful Bids and moves up the SPECTRE Track.

There are a lot of things this game gets right. But…

“East, West—just points on a compass.”

The components contain a few hits but more misses. The pawns mimic the SPECTRE logo, but in doing so feature an exceptionally weak connection at their base. Keep these away from small children folks! The SPECTRE ring would have been a much more appropriate and sturdy game piece. On the subject of pawns, I might call it lazy that the only difference between the Villain and the Henchman is the shape of the base. The list goes on. I cannot understand why the tokens on the SPECTRE Track are cardboard when they are often stacked and the order within that stack is important. Forcing players to fiddle with the stack to see who is in line to be Number Two, Three, or Four is inconsiderate.

From a graphic design standpoint, the seven Regions on the map have confused everyone at my table because the layout of information changes from Region to Region. Since each area offers both an immediate bonus and a round-end bonus, the flip-flop of information means players are constantly taking the wrong bonus for the moment.

I have seen a couple complaints that the game doesn’t feel thematic. I wholly disagree. In fact, I wouldn’t be surprised to hear the mechanics were born of the theme and not vice versa. In my mind I can hear the conversation in which they first considered a game that makes the Villains the protagonists and Bond the antagonists and the way they might fight for recognition in SPECTRE. There’s always room to push the theme further, but I think the Kaedama team succeeded. The asymmetry of the Villains, the eye for world domination, the loose bonds of the organization, and Bond on the loose. It all works. Maybe the convoluted rulebook is just part of the half-baked Villainous plot.

The Villains in the game are admittedly not the most iconic in the 007 catalog, but they are the gang most entrenched in SPECTRE lore. Dr. No is perhaps the most glaring omission. Like anyone familiar with the Bond universe (or maybe just the N64 implementation of the classic Golden Eye) I would also love to see what Villains and Henchmen like Goldfinger, Jaws, Alec Trevelyan, or Oddjob might bring to the table. I’m not sure what the team at Modiphius has in store for the intellectual property moving forward or whether the undoubtedly expensive deal included more names.

“It depends on which side of the glass you are.”

Obviously, the scales are heavily loaded when it comes to SPECTRE: The Board Game. For anyone patient enough to overcome the rulebook and the various production quirks, I believe there is a lovely gameplay experience under the surface. I’m not sure where things went off the rails between the original game design and the finished product, but I’m afraid the scales are tipped a bit too far in the wrong direction to expect the good sort of boom for this title. The retail price is hefty, and I’m just not sure it’s worth paying for so many mistakes.

However, if you are into Bond and you see the potential in the concept, you might just have the dedication and interest to mine the depths of the organization. Personally, I’m not scared off just yet. I’ve played a couple nail-biters so far, and I believe the game has more to offer, but that semi-endorsement comes with all sorts of asterisks.

Add Comment