Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

A century after the Prohibition era seems about the right time to celebrate the willful defiance and unmitigated glamour of the American speakeasy. Having never been to the 1920s myself, I write not from personal experience, but those folks sure appeared to be having a good time. Celebrities of stage and screen, flappers, gangsters, and Jazz music make lovely fodder for a roarin’ board game.

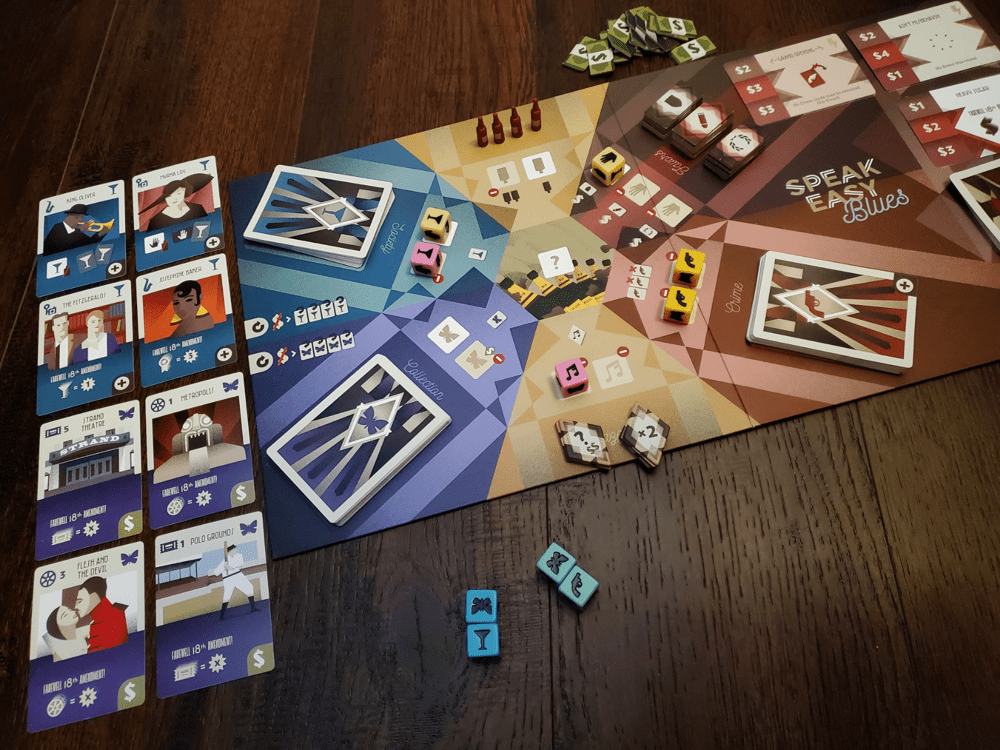

Speakeasy Blues is a title from Artana Games designed by Adrian Adamescu and Daryl Andrews, the team behind Sagrada, Dice Theme Park, and several other bang up games. In this offering, players are given the chance to defy the 18th Amendment and operate their own illicit gin joint in pursuit of fame and cash, but mostly just fame.

Between the theme and the design team, I am predisposed to enjoy Speakeasy Blues, but the proof is in the playing and, in this case, in the tiny bottles of hooch.

The Speakeasy

The central board of Speakeasy Blues is a ring containing seven actions, six of which share their icons with the faces of the custom dice. Each action contains one to three dice-shaped locations. The seventh location, of course, is a wild that need not match any particular face. The game’s ten dice come in five pairs of different colors.

The central mechanic at work is a true gem. Each player’s turn begins by retrieving one colored pair of dice from the board, opening two locations, and rolling them into the dice pool. Another dice pair is then selected and sent back to the board according to the icons rolled to determine actions. These two relatively simple choices create all the fabulous tension. The dice play then becomes a vehicle to set collection, with a handful of helpful mechanisms to expedite the process and occasionally bend the rules.

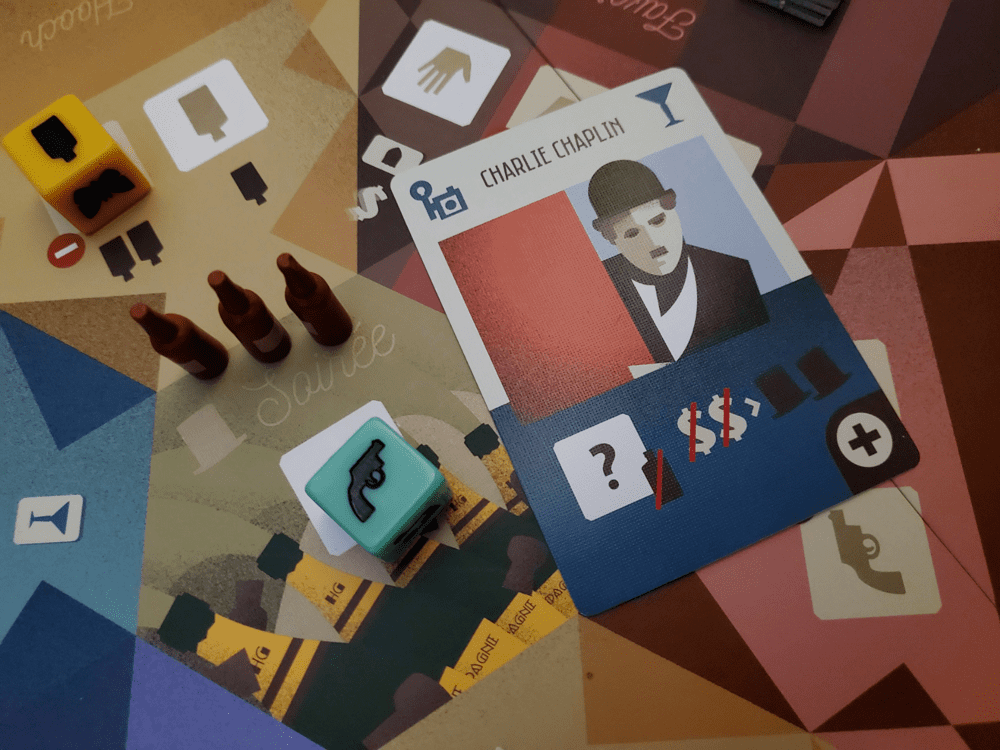

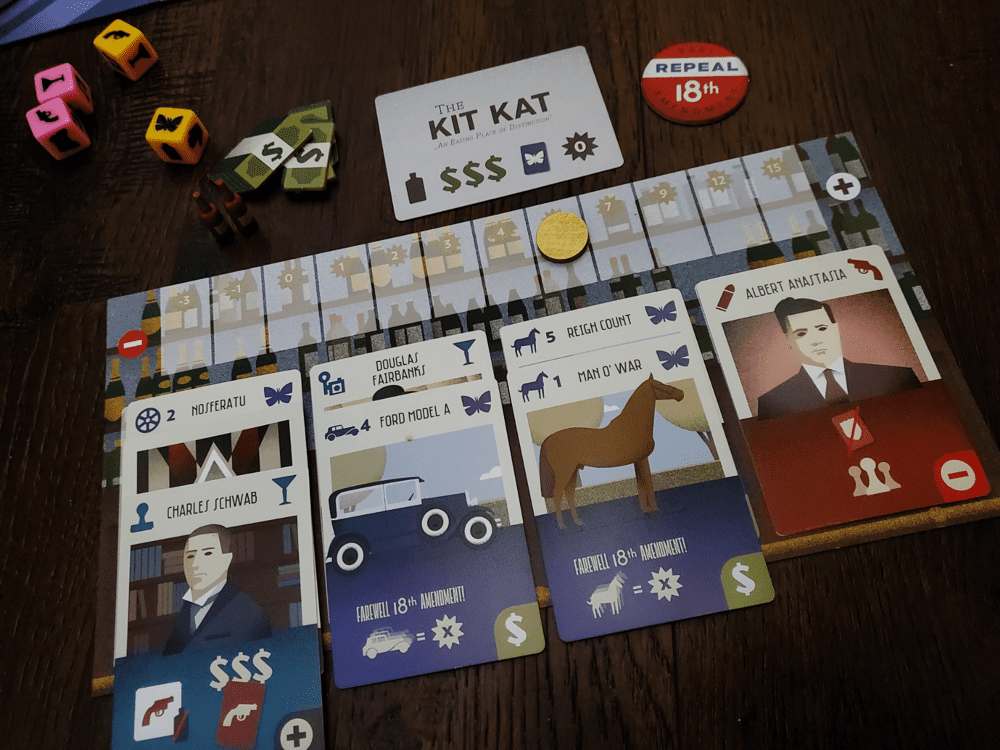

Society cards bear the celebrities of the day. Ball players, pilots, musicians, and the like, each bring either a quick shot in the arm or a rule-massaging ability. The cost for each special ability is typically a bottle or two of hooch, the speakeasy’s most adorable little component. (I was getting set to call them Barbie-sized bottles, but they are even too small for her iconic little hands.) Giving society-folk a bottle and a buck or two goes a long way toward extracting bonuses from the game’s various actions.

Collection cards represent the excesses of the age. Cars, boats, and cinematic experiences are lined up like the symbols that they are in the hopes of boasting the finest assemblage at the end of the game.

What would a game like Speakeasy Blues be without a taste of Prohibition’s seedy underbelly? Throughout the game, players attempt to curry favor with two crime families and the Police in the hopes of living outside the bounds of the law to the greatest success. This favor comes either by visiting the Favors action, collecting tokens and cash in the name of sweet, sweet bribery, or drawing Crime cards.

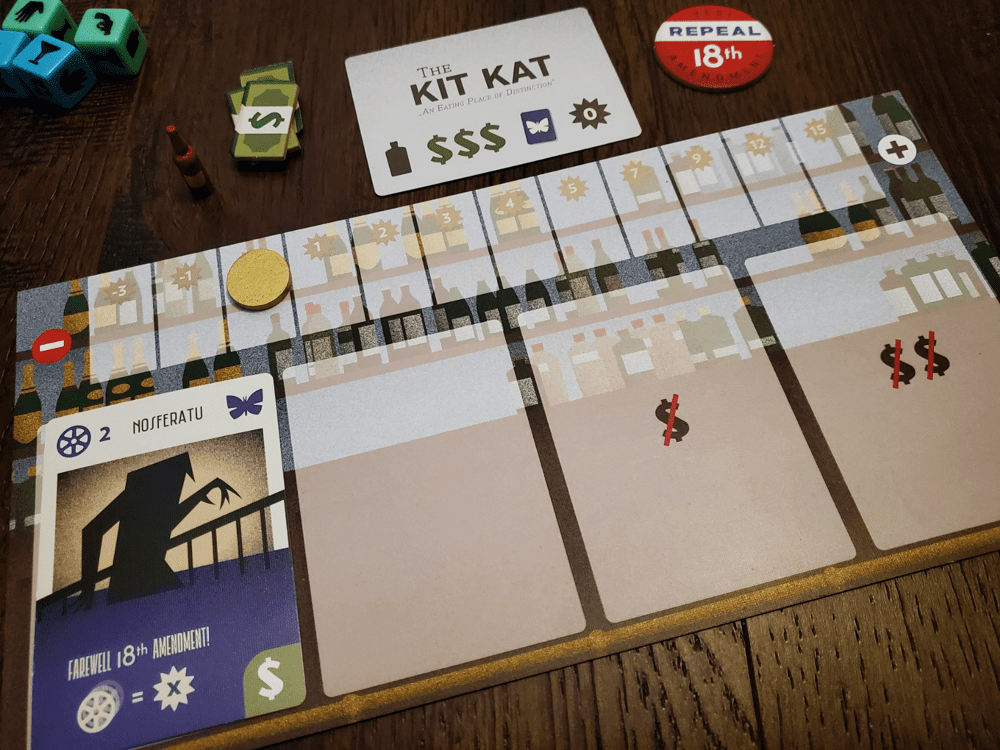

The cards function with a bit more nuance. This is as good a time as any to elaborate on the player board. There are four slots into which the various cards are drawn. Two are available from the start, with the additional two requiring a purchase using cash. Throughout the game, every card collected is owned, but only the topmost cards in each slot may be utilized for their effects. Herein lies the remainder of the game’s tension: choosing when to cover cards is an interesting mechanic that forces difficult decisions, especially with regard to endgame bonuses, which I will discuss shortly.

Crime cards are played into the slots face down. During a future turn, if a card remains on top, it may be flipped. Crime family cards can be played to shake down neighbors for money and other advantages. Police cards can then be flipped in response to the family cards, negating the shake down and instigating powerful abilities. As the cards are all face down, one never knows whether their devious attempts will pay off or simply grant another player a game-altering advantage.

The hooch action increases the stock of the good stuff, and the Jazz action bestows a token to either double a future action or change the face of a die.

The Soiree, the final action, can be activated by any die. Each card in a player’s tableau bears a mark in the lower corner of either cash or Prestige. Throwing a soiree grants the player every visible bonus. Prestige amounts to a straight points grab in the endgame. Players start at zero, and various actions send the token up and down the player board throughout the ten rounds.

Each round comes with either an Event—a temporary modification—or a Contest that will grant endgame points to the player with the most of some type of card. When the final event passes, the game is scored.

The Blues

The scoring in Speakeasy Blues is not exactly intuitive.

Oh, I suppose certain aspects are quite simple. Players add up all their Favor tokens and Crime cards and score both the Masseira and Maranzano families (Yes, those are real crime families. All the names and faces are historical.) and the Police, with each yielding points. Leftover cash and bottles of hooch are worth points, and those Contests are pretty clear cut.

But the Collections? Not so much. On the one hand, each collection card is worth a point. On the other hand, if a player has a particular Collection card type on top of a given slot (e.g. cars) then the player receives points equal to the purchase price of every card in that collection, regardless of its location. This is where paying attention to the cards atop each slot becomes critical. Having a large collection of boats only really pays off if a boat ends as the topmost visible card. Multiple collections may be scored this way, which makes tableau management tight and, at least at first, quite confusing. I’ve had players, after multiple plays, still not fully grasp the wide swath of scoring—especially the Collections. It’s not difficult, but neither is it natural.

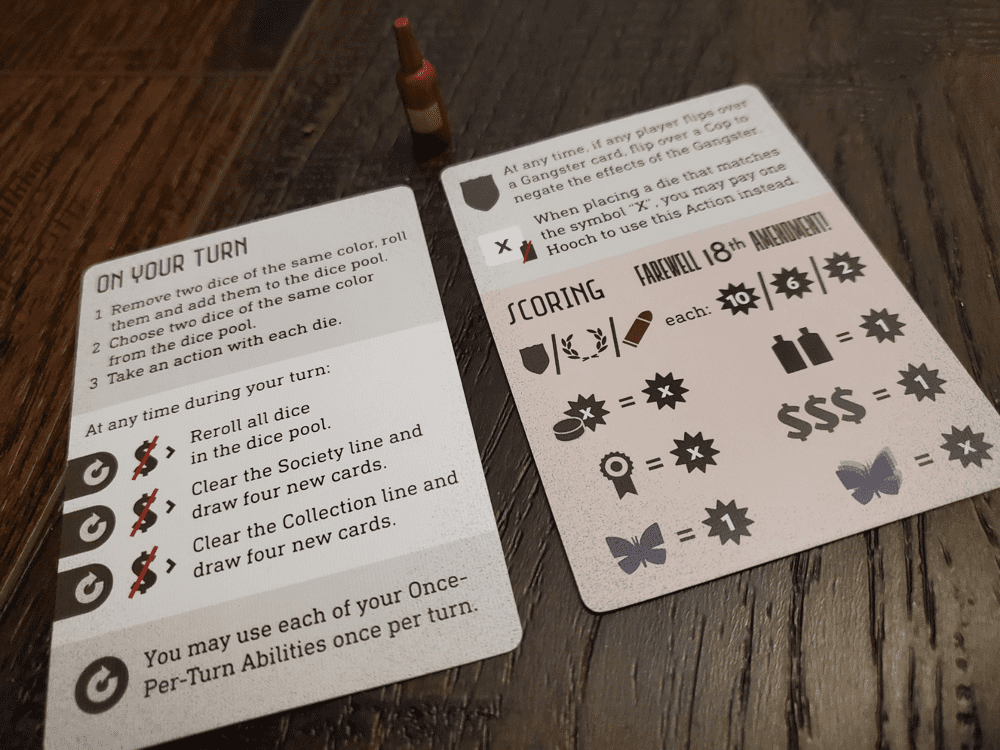

There are ten scoring categories in total. The player aid keeps all the various categories visible all the time via iconography, but some of the iconography is specific to the endgame. When icons are used throughout the game, fluency only requires a certain number of turns. But when the icons are only used in the endgame, that fluency is harder earned and a hindrance to planning a strategy without reading the rulebook a time or two. Plus, with ten categories, a scorepad is an assumed necessity that, somehow, was overlooked.

In many ways, the scoring intricacies constitute the attempt to push the game past a simple gateway experience—there are several paths of varying degrees on the way to victory. But in other ways, the layered assortment betrays the simplicity of the game itself. Now, to be fair, the quirks don’t interfere with my enjoyment, but comments around the table warrant the discussion.

Speakeasy Blues?

Speakeasy Blues is a solid little game over which, at present, I have three struggles.

First, the cover. This has to be one of my least favorite boxes. Ever. Which is a shame, because I love the understated simplicity of the game itself. The Art Deco style is perfect in every way, but I just find the box to be out of place. Having a singer on the cover? Great. The smoking? Whatever. But the image just isn’t appealing. I always find myself making sure this box is under another box on the shelf, just so I don’t have to look at it. I added the game to my collection despite the box out of curiosity toward the dice mechanic, but I would just as soon swap the box for a plain white box with the title written in Sharpie.

Second, the title. I’m not entirely sure why the game is called Speakeasy Blues. The music of the Prohibition era is unquestionably Jazz, and every reference in the game is to Jazz music. The two are related, but also rather different. There are blue notes in Jazz, but I’m not sure I would have gone there for a title. So why the blues? Without a lick of melancholy or an underlying color predilection, I’m just not sure. Call me particular, but I would have loved a different title.

Third is the scoring, which I’ve already discussed. More so than the scoring itself, I think my issue revolves around the presentation of the scoring. The subpar player aid and the absentee scoring pad add an unnecessary cover charge to what is otherwise a lovely night on the town.

Speaking Easy

Those three struggles aside, I really do enjoy this brand of speakeasy living. The central mechanic is wonderful for a lightweight strategy game. The dice removal is a double-edged sword that imbues the board and pool with potential energy. Perhaps the four dice in the pool already contain the desired faces for the upcoming turn, and the removal is merely a key in the lock. Then again, perhaps the faces aren’t there and the roll is more significant. Maybe there’s a plan afoot to spend a buck to reroll the entire pool. Who knows? I love when hope lights the way for a turn, but here there are no guarantees of success and therefore swift adjustments are required.

Speakeasy Blues flirts with head-to-head competition, but never wholly gives itself over. The Favor tokens, along with the Crime and Police cards, keep everyone’s eyes shifting about the table in competitive curiosity. The Society folk are unique and, depending on the Contests that enter play, may elicit a bit of a race to their acquisition. Likewise, for the Collection cards. None of these interactions will set the world ablaze with fits of disappointed rage, but they may continually alter tactical thoughts. Gin Joint management is largely a private endeavor, but there are constant reminders that you are not alone around the table.

The three-player contest might have the best balance. With two players, the game is lightning quick, but there isn’t enough turnover in the cards from round to round to force creativity. With four, play slows considerably because the landscape changes quite a bit between turns. In fact, with all those players, we cycled through the entire Collection and Society decks more than once. I tend to like a bit of mystery as to what will appear from outing to outing, but not so much that the game loses variety—and not so little that strategies are stifled. Perhaps the sweet spot lies at three, but I can’t say I’ve been disappointed at any count.

I am prone to enjoy a game set in the 1920s. I love loading a Jazz playlist and sitting down with Babe Ruth, Charlie Chaplin, and Amelia Earhart. I love that the Collections smack of the sort of excess you’d find at one of Jay Gatsby’s parties. I love the interplay of the crime families and the Police. Thematically, this is a winner. Mechanically, as I’ve already intimated, this is mostly a winner. Were it not for a few unfortunate aesthetic and skeletal hiccups, I can’t help but believe Speakeasy Blues would find a wider audience.

If you’re into the era, I believe you’ll love the game. If you’ve enjoyed the work of Adrian Adamescu and Daryl Andrews, this is yet another worthy use of dice. If you’re turned off by the box, gift wrap the lid and break out the Sharpie. If you find it on a nearby table, I don’t think you’ll regret giving it a chance.

Add Comment