I am not a digital gamer—not at all. Apart from my tenuous excitement to explore and review Everdell Digital and a very, very brief flirtation with the mobile version of Sagrada, I can’t say my aversion has wavered. Give me the cardboard any day.

That being said, one tabletop game holds the distinction of making me say, “Wow, this one should probably be an app.” That game, my friends, is Small World. I know I say give me the cardboard, but Small World takes its cardboard seriously.

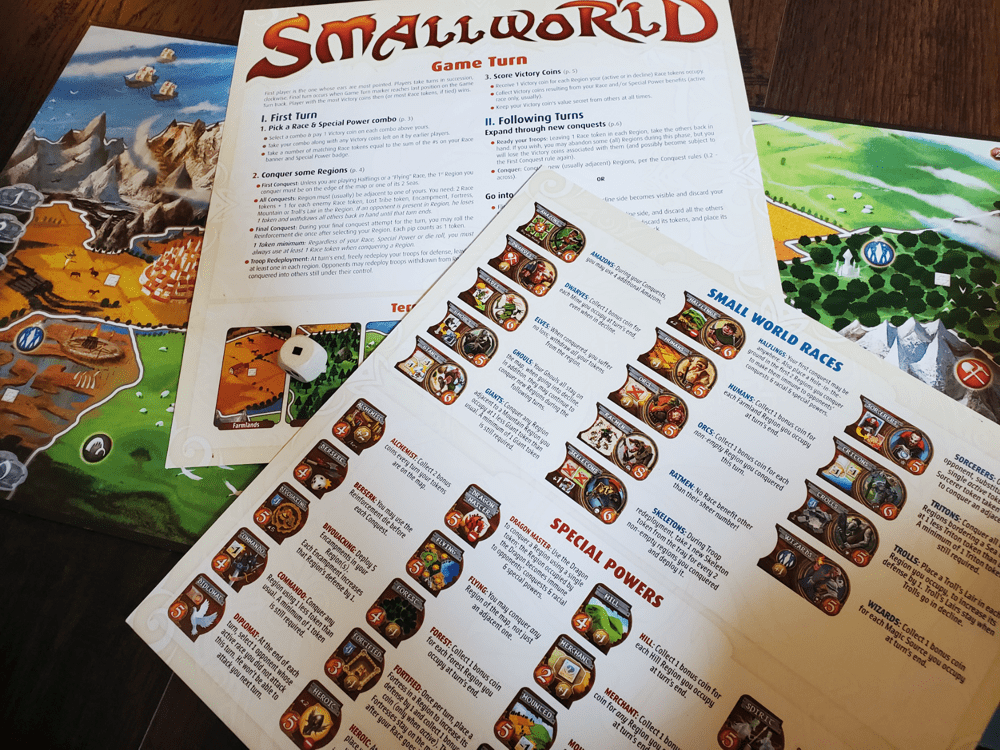

It’s not just tokens upon tokens. I’m sure many games have more than 365 punched bits, right? It’s the constant handling of tokens upon tokens that first lured so bold a statement from my lips. Of course, I was late to the party and the digital version had long since dropped by the time I had my insight. With all the lifting, placing, removing, reorganizing, sliding, swapping, face-up and face-down, I suppose something had to be done.

Despite the fidgety-ness on the table, Small World is a rock solid game system deserving of its place in the tabletop universe—solid enough to engage the abundantly tactile production again and again.

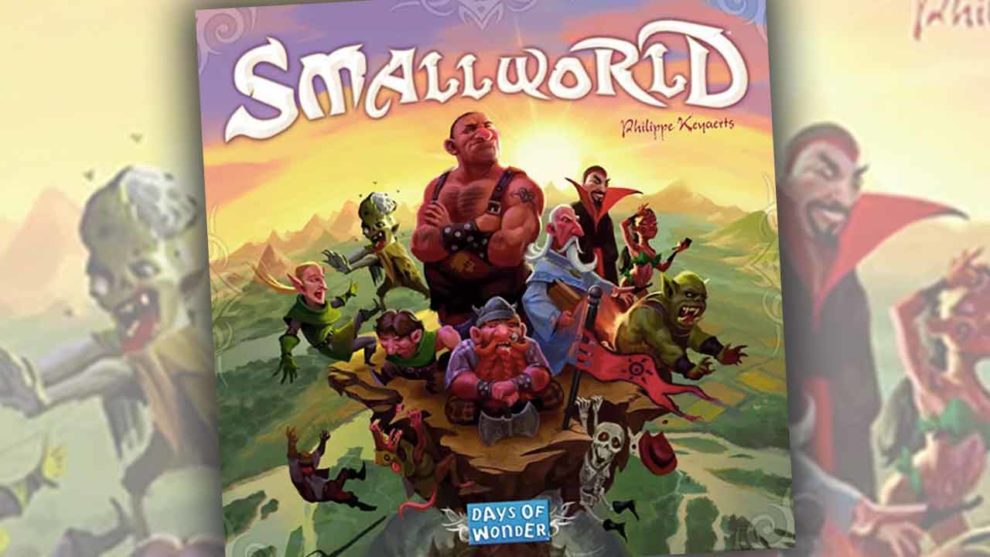

The bottom line: Days of Wonder picked a winner when they decided to make over Vinci, the area control classic that garnered an Official Recommendation in 2000 from the folks at Spiel des Jahres. Both Vinci and the veritable gaming empire that has grown from the base edition of Small World are the design of Philippe Keyaerts, and they’ve withstood two decades in the industry with no end in sight.

Earlier today I pulled my five-year-old daughter to the table to join us for her first game of Small World, which made me think it’s time to write a few words.

What’s all that cardboard for, anyway?

Small World takes place on a map that, fittingly, isn’t large enough for all the races vying for geographic supremacy. This area control battle pits archetypal fantasy races against one another. Each race has its own characteristic strength and is bolstered by a special power that aids in the bid for dominance. These pairings are revealed in a running queue during play—just one area of cardboard maintenance.

Once selected, each race comes with a set of tokens for use on the board. The battle system is downright simple. In order to defeat a territory on the map, players must place two tokens plus one for any other token already present. These extra tokens might be mountains, lairs, or encampments that provide extra protection to one of the races. Most player turns consist of placing tokens until there aren’t enough to win anymore. At this point, provided they hold at least one unused token, the player may roll a die for reinforcements to settle their final attempted conquest. Once the fighting is complete, players are able to shift their tokens around to prop up vulnerable territories before collecting a Victory token for each of their occupied territories.

When a race has become war-torn and fragile, players may send it into decline by flipping a single token to its shadowy backside in every occupied territory, indicating they will select a new race-power pairing in the following round. Each player may have one declining race on the board in addition to their active, collecting Victory tokens until it is eliminated completely.

Aside from some of the specific quirks of attempted domination—how tokens enter and leave the board, how the various territory types aid specific races and powers, etc.—these are the nuts and bolts of Small World. Every turn is a constant barrage of cardboard activity. Depending on the player count, eight to ten rounds are sufficient to declare a winner.

I couldn’t imagine it any other way

Small World has become a retail commonwealth all its own over the past 14-plus years. Between full-blown expansions and power packs, there are many dozens of races available to both the aficionado and the amateur. Horror, Legends, and highly-prized video game partnerships meet over land, air, and sea, each with their own chits and tokens. If I had the disposable income and time, I would love to dump every component out of every organizer tray just to see what sort of girth inhabits this franchise.

But, as I said at the beginning, it’s solid. I only own the base game. We only play a few times a year, but I really do enjoy Small World for its relative simplicity despite the wealth of bits.

Battle couldn’t be more user-friendly when counting as high as six or seven is the basic skill involved. Drop enough tokens and the other team takes their equipment and goes home. I really appreciate that not every defeated token is driven from the board (though one is), but that there is room for theoretical retreat to safety at the turn’s end. Battles are instantaneous, and the only intrusion of dice and randomness waits until the end. The simplicity allows the ever-changing board state to be the star of the experience. There’s no room for sentimentality with such flux.

This simplicity gave me the confidence to call my young daughter to the table. Obviously there is a lot more going on with the interaction of the map and the races, deciding how best to branch out, when to enter decline, and how to evaluate the board state. But she could certainly take her Alchemist Skeletons and run roughshod over the map. Once I explained that she is rewarded with more Skeletons for conquering rather than taking empty territories, she understood enough to start picking on people. She held those Skeletons for 7 rounds and didn’t finish last (among four players), a testimony to the fact that anyone can play Small World with relative success.

For the more tactical mind, however, Small World offers a bit of heft as well. Reading the possibilities inherent in the race-power pairings, the opportunities on the map, and the intentions of the other players at the table takes a bit of mental effort. The choice of how often and when to decline is critical to creating passive income. Over and against the minimal use of the die, there is less luck and more cold calculation in the area skirmishes. Winning feels like winning because players are not operating according to the whim of fate.

Even limited by the base game’s fourteen folk-types and twenty unique powers, the random combinations make for a healthy variety from game to game. There are box-sized player aids with full descriptions of every race and power on one side and game details on the other, a massive help until the iconography clicks. A pair of two-sided boards with different maps for every player count also guarantees a bit of novelty for each outing. The limitless additional variations in the marketplace hurt my head to ponder. If you’re into the gameplay, this “World of Slaughter” is not likely to go stale.

The largest portion of the cardboard—168 race tokens—is actually quite nicely organized in a molded tray to keep life in order. That order comes with effort, but it is order nonetheless. The Victory tokens are the greatest inconvenience because they are stored in four slots in the insert. Taking them out and putting them back is annoying. Coin slots, broadly speaking, are probably my least favorite insert feature in any game (I’m looking at you, Camel Up). Overall, though, the insert is helpful. I mock the copious cardboard with a wink and a nod.

Small World ebbs and flows with my family. I’ve yet to consider trading it away because we come back from time to time and relish a battle or three. Now that our youngest has a grasp of the basic mechanics, I can see her asking for “that little world game” more often. When it’s out, we really do enjoy it. I admit, sometimes we just forget it’s there, but there’s a constancy in Keyaerts’s design that always delivers (and has delivered since the Vinci days). Though the game is now a teenager, the artwork of Miguel Coimbra and Cyrille Daujean hasn’t aged badly like many of its pre-2010 contemporaries. Like I’ve said all along, it’s solid.

I’ve looked into the expansions at times, and I could see myself grabbing one if the winds are favorable, but I’m in no hurry—we enjoy it as is, and I know Small World will be around for years to come.

Add Comment