Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

I’m diving into train games in a big way in 2023. After learning the 18xx system a number of months ago, I have been aggressive in finding these games as I try to learn the ropes.

Earlier this year, I shared my project idea with Josh Starr, the person who runs Grand Trunk Games. About two years ago, I purchased 1861: Railways of the Russian Empire / 1867: Railways of Canada (the two games can only be purchased as a box set), the first Grand Trunk production following a successful crowdfunding campaign.

1861/1867 are beautiful second editions. It is clear that Josh only wants to put his name on sensational productions of classic games, while also finding ways to draw new 18xx gamers into the system. Josh’s second project is a reprint of a game long out of print. Originally released in 2004 as 1889: History of Shikoku Railways, the game is famously known as one of the best, if not THE best, introduction to the 18xx system.

I got to know the game a bit better through the 1889 implementation on 18xx.games. Now that I have a physical copy at home, I’m even more excited—it’s great to own a game that teaches curious players about a somewhat intimidating system. While Shikoku 1889 is an exceptional experience, I don’t actually think it is the perfect introduction to the 18xx system.

Shikoku, Baby

I won’t break down the 18xx system rules here—feel free to browse my 18xx introduction for that, or find any of the incredible sites online that break down how the system works. Here, I’ll share my thoughts on what differs in 1889 versus other 18xx games.

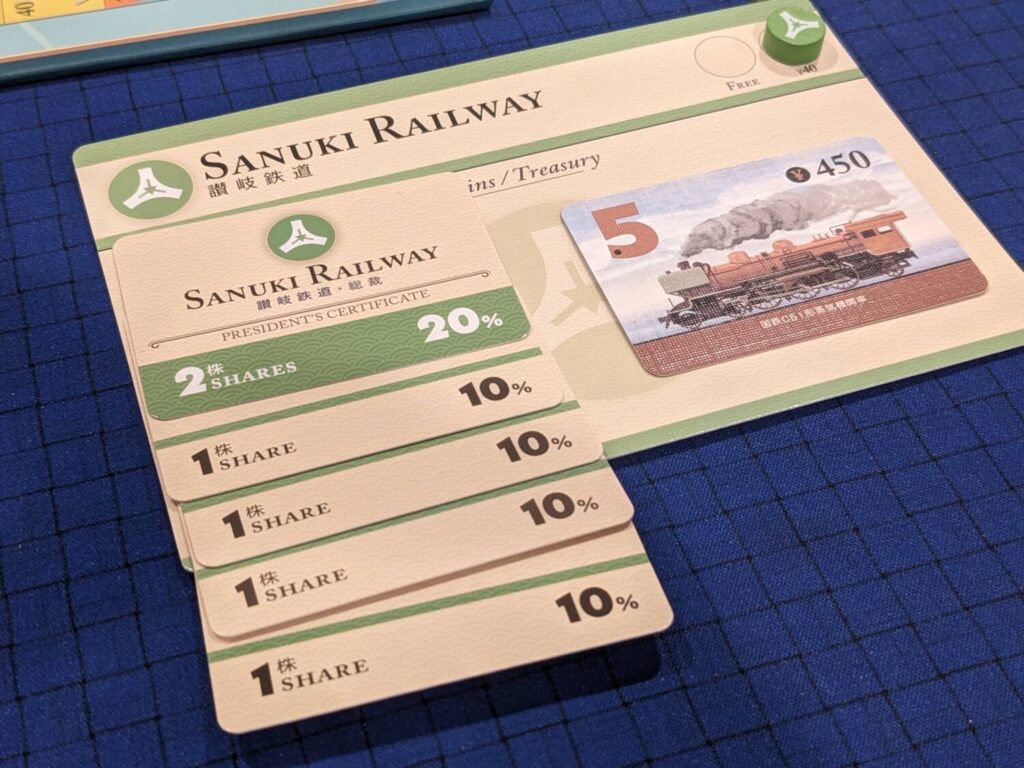

Many of the staples introduced in Francis Tresham’s games 1829 and 1830 are present in 1889. Players take on the role of investors in private and public train corporations in the 1800s. Public companies require a certain amount of shares to be bought in order to “float” (begin operations, in train game terms). In the case of 1889, that is 50% of the company’s par value (the initial share price, anywhere from 65-100 yen).

Shares can be sold, then a single certificate can be bought, then sold in stock rounds. Later in the game, any shares originally bought from the IPO then sold are placed in the open market. Shares in the market earn money into that company’s treasury, and there can never be more than 50% of a company’s shares in the open market.

Otherwise, the stock rounds in Shikoku 1889 model most 18xx games I’ve played. Operating rounds are likewise standard fare here. Companies may lay or upgrade a single track tile on a turn before optionally placing a station token. Tile colors are limited to yellow, then green, then brown in 1889; there are no gray tiles, but there are a few gray spaces pre-printed on the board that can not be manipulated.

Revenue centers are mostly cities in Shikoku 1889, with a very small number of towns that count as a stop on a train’s routes. Off-board locations have three values instead of four—one value for the yellow and green track phases, one for brown track phases, then a much higher value if a diesel train is later able to include that location in its route.

The major shock I had during my first game of Shikoku 1889 is the extreme lack of tiles available to players. The base game only has five pieces of straight yellow track and five pieces of “gentle” curve track. That means that players have to be a little aggressive in upgrading track if they are going to free up track for new corporations. That also means some of the strategy in Shikoku 1889 is aligned with NOT upgrading tiles, severely limiting the options of other players.

Even in the case of green tile upgrades, most of the standard track options are here, but usually there is only one of each green track tile. During a recent in-person play with four other players (all new to 18xx), I spent a lot of time explaining how rare it is that a game featured so few options for track. That’s a benefit for new players—when it’s gone, it’s gone, right?—but I can see why some players have beef with this feature.

Personally, I find the lack of tiles to be a benefit. 1889 is streamlined in almost every way, and I love that about the game.

Tidy (Like Japan)

I spent two weeks in Japan about ten years ago, and I am surprised to say how much I love the tidiness of both real-life Japan and Shikoku 1889’s version of Japan and the resources in this game.

The map is small, much smaller than some of the other 18xx games I have tried. (I’m looking at you, 1880: China!!) There are seven public companies available, and some of them only have one station token, the one that is placed for free when beginning operations. The train pool is very small, with a very limited number of 3, 4, 5, and 6 trains. (In Shikoku 1889, this number represents the number of stops for both cities, towns and off-board locations.) I was shocked that there were only three 5 trains in this game. The train rush is real!

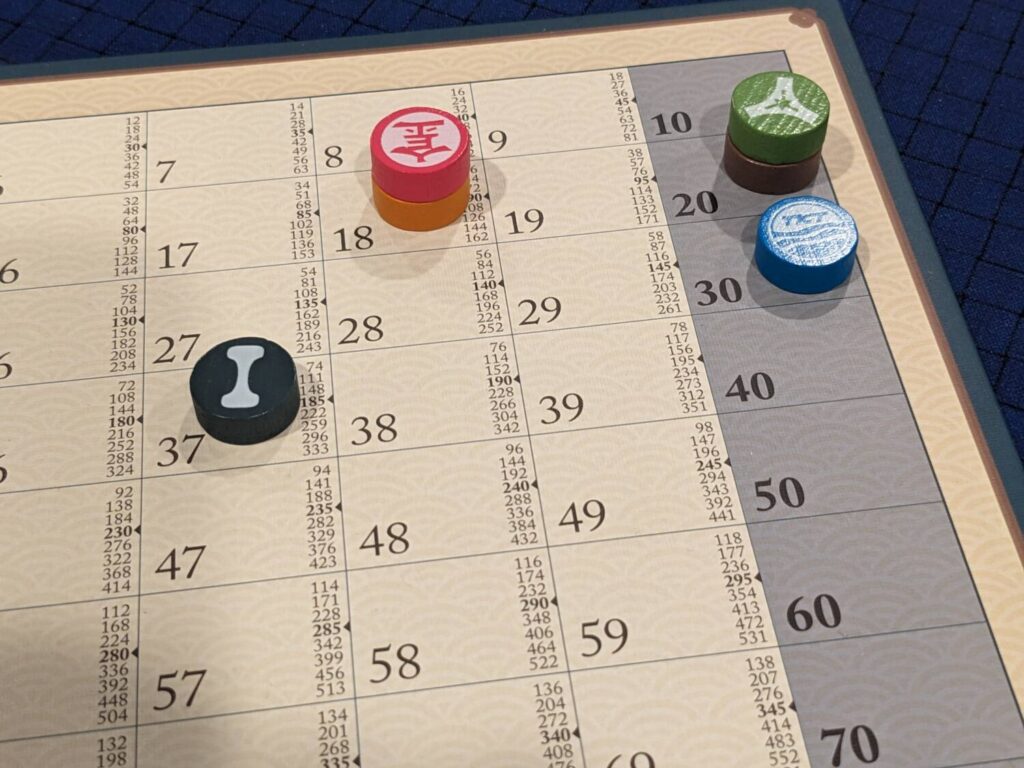

I don’t know if this was the case with the first printing of 1889: History of Shikoku Railways, but the new board is exceptional. Everything fits on the board except for the revenue tracker. The stock market takes up nearly half of the board, and it is so clean. There’s a perfect little cheat sheet in the form of a visual aid indicating how share prices move from turn to turn in stock rounds, and I am constantly referring new players to it during play.

The Shikoku 1889 operating map has a number of visual cues that provide easy ways for players to understand the differences in each hex. The mountain spaces are a nice shade of brown, and the tile price (if applicable) is very easy to understand. Ditto for densely populated city locations and river hexes. I’ve gotten a number of questions from new players on how those work operationally: why does it cost to upgrade so-and-so and not other tiles? However, in terms of the visuals, Shikoku 1889 is a masterpiece in functionality.

The embrace of “tidy” continues with both the rulebook and the fantastic player aids. Oh my goodness, I love this player aid!! Almost everything a player needs during the game is here. The things that change with each phase (aligned with new train availability) are listed on one side of the aid, including when trains rust, what tiles become active, and when privates close.

Many 18xx productions have aids like this, but they are sometimes listed as a separate board. That can make things hard to read if you have a seat far from those shared aids. Not so with Shikoku 1889. Information is sitting within easy reach of everyone thanks to the aids and the visuals on the board. For new players, this is great.

And did I mention that there are two trays to hold tiles included in the box? Honestly, I’m not even sure this was necessary given how few tiles there are for this game. But that’s also why I love that the trays are here. Shikoku 1889 has the look and feel of a luxury good, both with everything inside the box as well as the very handsome cover art designed by Karim Chakroun.

Even the paper money is great, at least if you believe in using paper or card money for 18xx games. (I don’t.) The whole thing is just tidy, a lot like the clean streets of nearly everywhere I went in Japan.

100% Go

As much as I love Shikoku 1889 as a game, I might love it even more as a production.

18xx games get a bad rap in the production space. (Or, maybe they get the right rap, because I have admittedly played a couple of ugly ducklings.) Shikoku 1889 takes a path many tabletop productions are doing with second editions and reprints of games long out of print—don’t touch the gameplay, but make everything about the production really shine. Then, players feel like they are getting the best of both worlds: a solid game paired with exceptional components.

Shikoku 1889 is that and then some.

Now, as an introduction to new 18xx players…Shikoku 1889 is good. My main beef with it isn’t the mechanisms, the 50% float, the lack of trains or tiles: none of that. It’s that the bank is too large, meaning that games of Shikoku 1889 with new players might run long (much longer than the 2-4 hours listed on the side of the box). Games of Shikoku 1889 are certainly going to be shorter than 1830: Railways and Robber Barons, which is a death march in the wrong hands.

A starting bank of 7,000 yen is too much for new players. In fact, I usually short the bank to ensure a game that could end in under four hours (5,000 yen feels just right). I want people to come in, give the system a spin, and be done with their first play. Yes, that means you are probably not going to see much beyond the purchase of the first 6 train and an operating round or two after that. Fine, knowing how diesel trains work isn’t that big a deal as a selling point for a new player.

The Shikoku 1889 manual has a variant for new players that skips the private company draft, and I highly recommend it because new players have no idea what the real value is of, say, Ehime Railway, when it comes to understanding the cost versus the value proposition. The bigger benefit is a savings of at least 30 minutes of play time thanks to a drawn-out bidding cycle.

Otherwise, Shikoku 1889 is world-class. I don’t get the chance to play a lot of designs that are this good. If you are looking for a compact, entertaining train game and another reason to get those poker chips into action, Shikoku 1889 is a must.

Thank you Justin for inviting us along on your journey through 18xx. Having recently ventured down the same rabbit hole, your thoughts and analysis have been on point and helpful.

Sure thing! More 18xx content is on the way!