Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

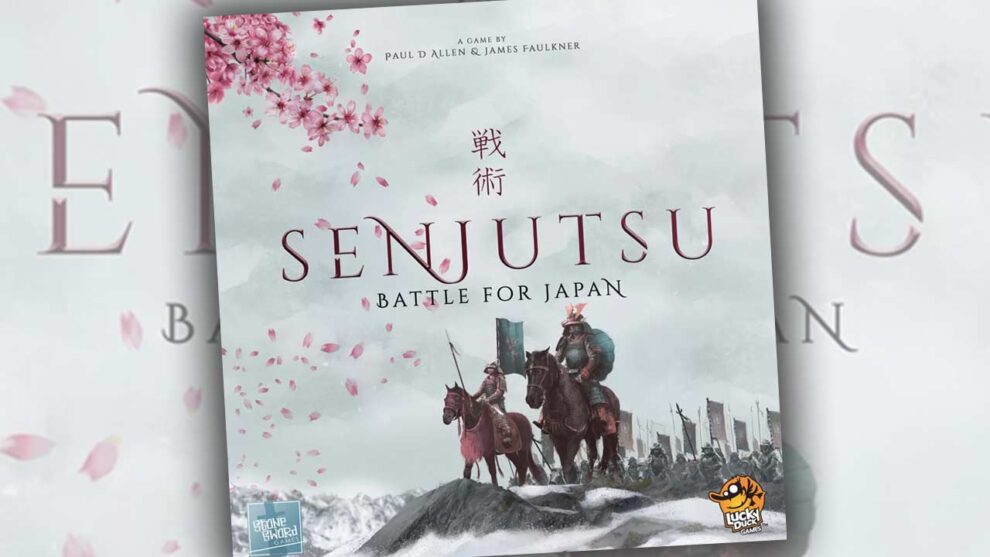

Senjutsu is a skirmish game for 1-4 players, set in feudal Japan during the civil war that followed the fall of the Ashikaga Shogunate. Each player takes on the role of a samurai protecting their Daimyo, but the narrative doesn’t make its presence known. This is Street Fighter in three dimensions. Another name for that might be Tekken. Players battle it out, trying to be the last man—hey, that’s what’s in the box—standing.

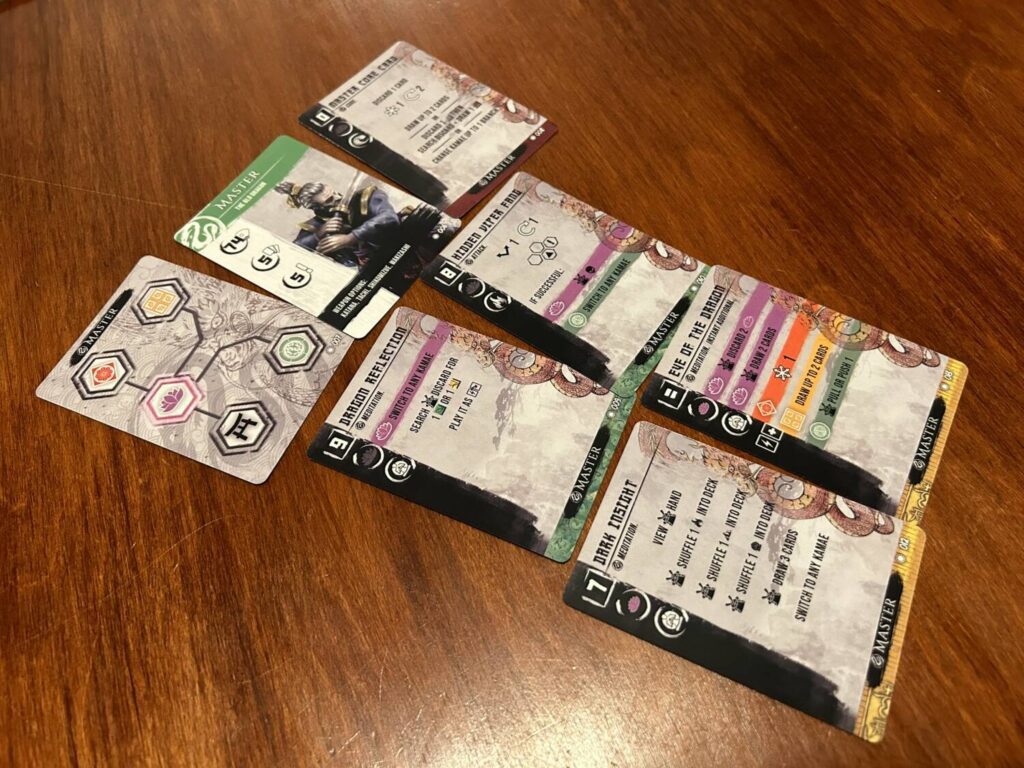

Mechanically, Senjutsu is a card game with heavily customizable decks. At the beginning of each session, both players construct a deck that corresponds to their chosen character. The flexibility of the system is tremendous. Each character has a set of special cards only they can use, on top of a large stack of general cards that can be used by anybody. This portion of the game reminds me of Sakura Arms, a dueling game in which players select characters and choose cards from within their supply. Though Sakura Arms is a bit tidier about how it implements its version of this system, Senjutsu offers a similar promise: the more you play, the better you know the characters and their cards, and the more emotionally satisfying the deck-building portion of setup becomes.

The game itself is quick, about 20-30 minutes for two players, and the rules are straightforward. Players simultaneously select and reveal a single card from their hand. Each card has some combination of movement, attack, card draw, and so on, along with an initiative value and potential costs. Players activate their cards in decreasing order of initiative.

There’s a good amount to consider. What stance are you in? What direction are you facing? Do you expect your opponent to move in anticipation of an attack? Can you force them into some terrain, stunning them? Are you at risk of being attacked? There’s a lot of guessing, a lot of tense double-blinds.

What starts as wild guessing rapidly becomes educated. Each of the four characters has a distinct overall feel, and as you learn that, you start making informed decisions. They’re almost never choices in which you can be fully confident: your deck doesn’t cycle. Unlike Sakura Arms or the Exceed games, you can’t learn anything about the specifics of your opponent’s deck as you go.

A big part of the appeal here is the presence of that third dimension. I’ve played a lot of dueling card games with these mechanics, but Senjutsu is the first time I’ve seen this system welded to a full board. The minis help flesh things out, and the interactions with terrain add a certain 何か分かりません (Je ne sais quoi). Most terrain causes you to be stunned, which diminishes your hand size. My favorite is the bamboo, which stuns and hobbles a player for the next four rounds. I enjoy the idea of a fearsome warrior accidenting into a bamboo patch, only to emerge dazed and a touch disheveled. Any time a game can incorporate comedy, I’m in favor of it.

The game supports 1-4 players, and all of the arrangements that I’ve tried have worked. I think it’s at its best at 2, but the solo mode and included mini-campaign are admirable, and the co-op 4-player mode is a blast. Thanks to the simultaneous play mechanism, there’s very little downtime, and it’s exciting to see things unfold. I worry 3 players would easily fall into a 2-v-1 dynamic, but I haven’t had a chance to try for myself.

I want to be clear that, though much of what will follow is negative, I think Senjutsu is a terrific game. The negativity in the latter parts of this review is in part a response to how good the game is despite all the ways in which its production lets it down. We critique because we love, etc.

On Production Choices in Senjutsu, a dissertation in two parts.

Part I: Card Tricks

It seems safe to assume that Senjutsu was designed with the intention of creating a lifestyle game. If you aren’t familiar with that term, lifestyle games are intended to be deep enough to constitute a hobby unto themselves. Think of Magic: The Gathering, or Warhammer 40K. Heck, think of chess. Even though that means Senjutsu is likely aiming for a niche audience, I think there are a number of small changes that could have been made during production to make it significantly more approachable for a wider audience without losing its appeal for that niche.

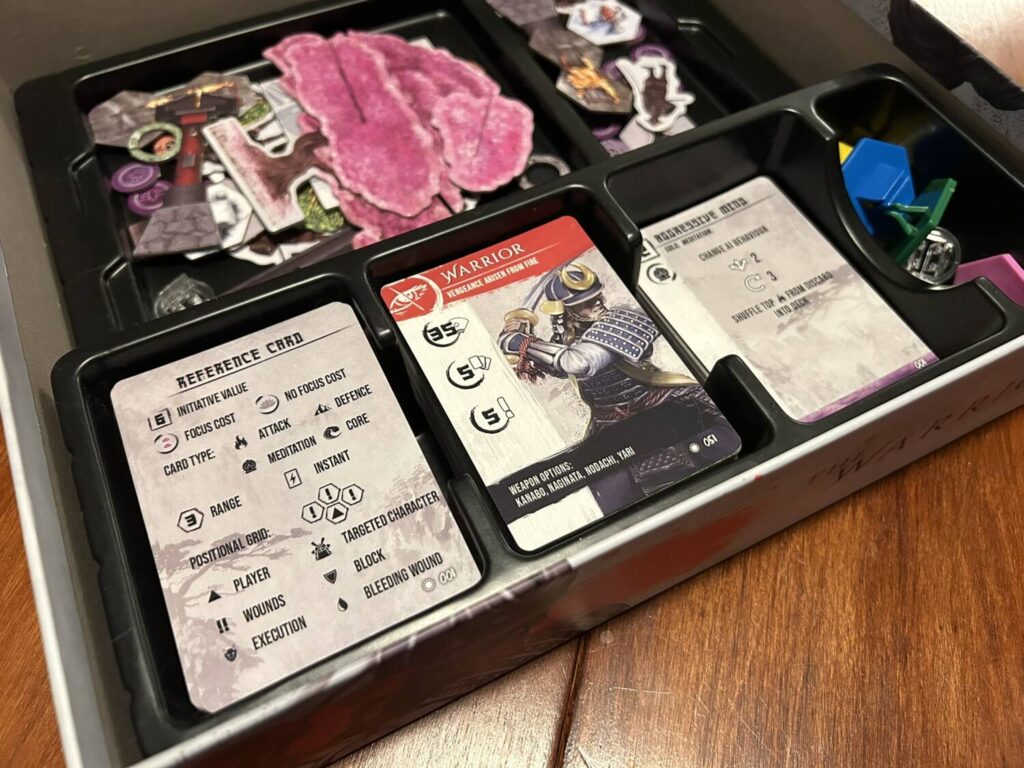

In the box, there are around 300 individually numbered cards, kept in numerical order in a giant stack. These are the cards you use to construct your character deck at the start of each game. Some of the cards are character specific, while others can be used for any deck. The rules for deck building are pretty straightforward, and the game does provide default suggested decks for starting players.

All together, this provides an incredible amount of flexibility, customizability, and leaves plenty of space for players to express their own personalities through their approach to the game. I love all of that. There’s a downside, though: getting started is a pain. Worse than the setup, you need to disassemble and reorganize all of the cards back into that giant, numbered stack at the end of the game. That is tiresome.

I can’t help but feel that Senjutsu’s long term prospects would have been better served by coming with those recommended starter decks pre-grouped, distinguished by a color or an icon, with a vertical slot for each in the insert, and all the extra cards together. It wouldn’t have increased the cost of production a penny. You can play with four players. The cards for all four decks to exist simultaneously are already included. That way, players who want to engage with Senjutsu as a serious, flexible design space can do that, while more casual players can just sit down for a quick game.

A similar issue presents itself with the solo cards, which are also organized in a single, numbered deck. The rulebook tells you, when constructing a bot deck, to separate the cards into specific piles before shuffling those piles and picking a varying number of cards from each. This is a cool system that provides significant variety to the solo mode. Each bot has a distinct character, but the randomness of card selection means they don’t grow stale. It is fabulous and robust design work.

Here’s the thing: the piles are always the same piles. Every time I want to make a randomized solo opponent, I’m supposed to separate solo cards 001, 003, 008, and 009 into one pile, while putting 002, 004, 005, 006, and 007 into another, while, etc., etc. In the meantime, if I want to play the solo campaign, the decks for each enemy are specified, which means I need to put these cards back into numerical order before I put the game away. I know why all the solo cards have identical backs, but why are the fronts not distinguished by color, or an icon, or anything that would keep me from having to look at that list every time? Why were the cards not even numbered so that cards 1-4 go in the first pile, cards 5-9 go into the next, etc.? This hobby has been around for a long time! We know how to do these things!

The card stuff isn’t a deal-breaker by any means, but in the long-term it will keep Senjutsu from getting to the table anywhere near as much as it otherwise would.

Part II: Are You F#¢&*ng Kidding Me with this Manual

I spent two (2) hours making my way through the Senjutsu rulebook before I was able to take a crack at my first game. I had to read and re-read to make sense of things. I often had to backtrack or flip ahead to understand something I was currently reading. On one occasion, I had to out-and-out infer, and there were several questions that came up that I eventually decided, after two (2) hours, were not worth worrying about.

There is no reason for this manual to be so impenetrable. The information is neither presented well, nor in a sensible order. I am astonished that Lucky Duck let Senjutsu out the door in this state, and I hope that a replacement is made available ASAP. There is no excuse for publishers with easy access to experienced professional translators, graphic designers, and technical writers to release a product like this.

Let’s Du-du-du-du-du-duel

I think Senjutsu is crackerjack, with levels of depth that would reward complete devotion. There are 300-ish cards in the base game, but there are only 128 distinct ones. It would be relatively easy to reach a point where you know the game inside and out. I want to give Senjutsu 4.5 stars, but I can’t justify that as the product exists. 4.5 on a mass market game, for me, reaches the point of “Just, stop reading this, go buy it.”

Due to the unfortunate intersection of the fussy card system and the atrocious rulebook, I would only ever recommend Senjutsu under specific circumstances. That’s really too bad. It’s a terrific game once it gets going. Matches take 20-30 minutes, they’re full of tense choices, and the board(s) look(s) great. This is one of the best dueling/skirmish games I’ve ever played, and you’ll almost certainly love it if you have the patience and motivation to get to your first game. Most people won’t have either, and, given that it’s a direct result of choices made by the publishers during development, I don’t blame them.