There has been a fair amount of hype surrounding a certain board game this year. It is a game of timing and intrigue about the brokering of souls—a game that plays exclusively at four players. I know what you’re thinking, but no, it’s not Deal with the Devil, though I suppose that one qualifies as well.

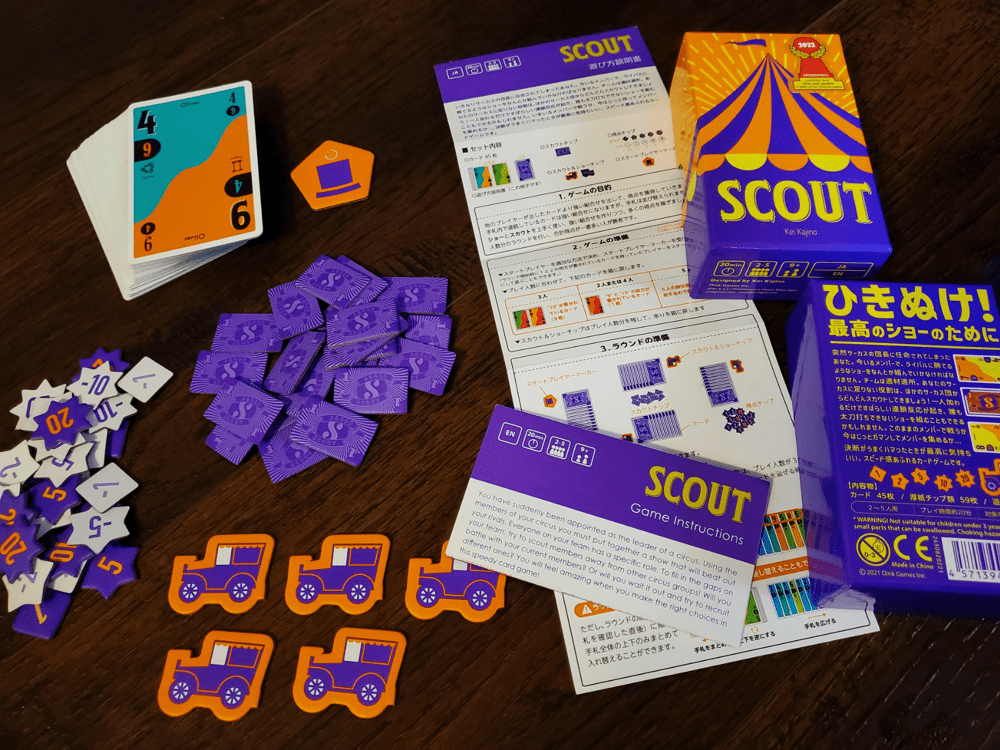

The game on my mind is much, much smaller. This game was a finalist for 2022’s Spiel des Jahres—a little game called SCOUT. Rather than stealing away humans for the service of darkness, this small box card game from Oink Games involves stealing away humans… for the circus.

I know what you’re going to say next. Bob, SCOUT is not a four-player-only game. I understand your point. I’ve seen what the box suggests. But I ask: isn’t it possible the box is overselling itself with that range of two to five players? As a more philosophical follow-up, allow me to pose one additional question: if a game is absolutely brilliant at a particular player count, isn’t it acceptable to own up to that fact with a bit of bravado and simply wait for the accolades to shower from every direction for being so honest?

In this case, I say yes.

When your circus isn’t as good as the next…

SCOUT is considered a ladder climbing card game, meaning that the object for each player is to “one-up” the previous play until someone finally takes the proverbial cake with an unbeatable hand. Under this big top, however, the real game is the healthy dose of ladder chopping as players Scout away cards from the current contender.

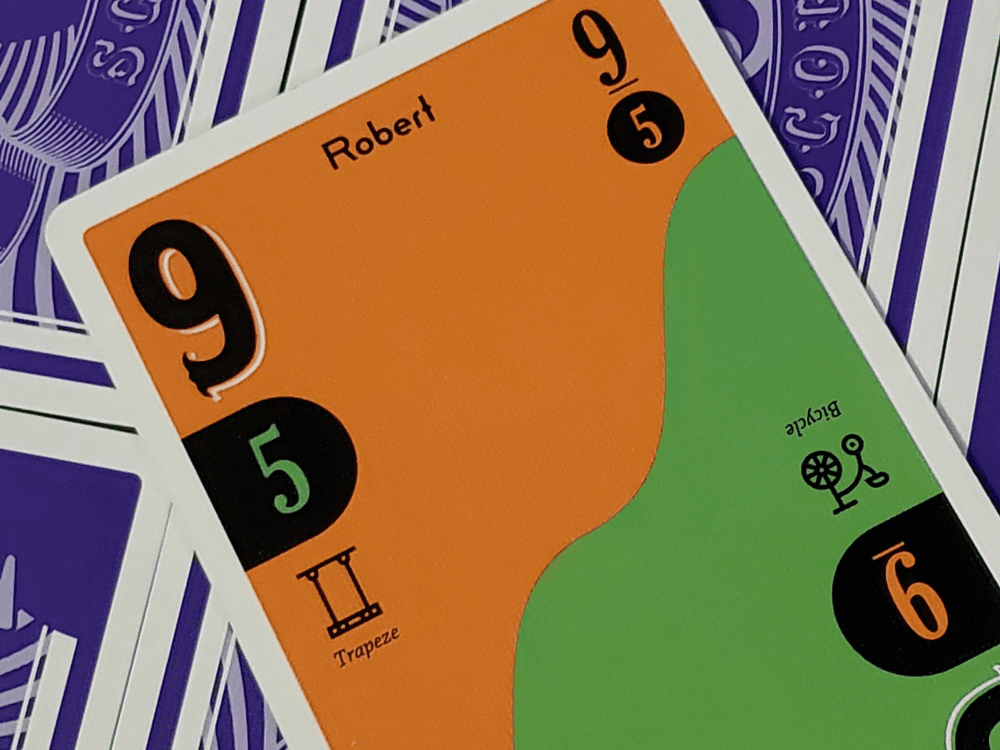

The cards in SCOUT are divided across the vertical diagonal with one number printed on each half. So the card’s options are always visible, the number on the other side of the card is also printed as a sort of subscript below. Yes, there are also performer names and circus specialties printed on each card, but the numbers are the only information that matters in play.

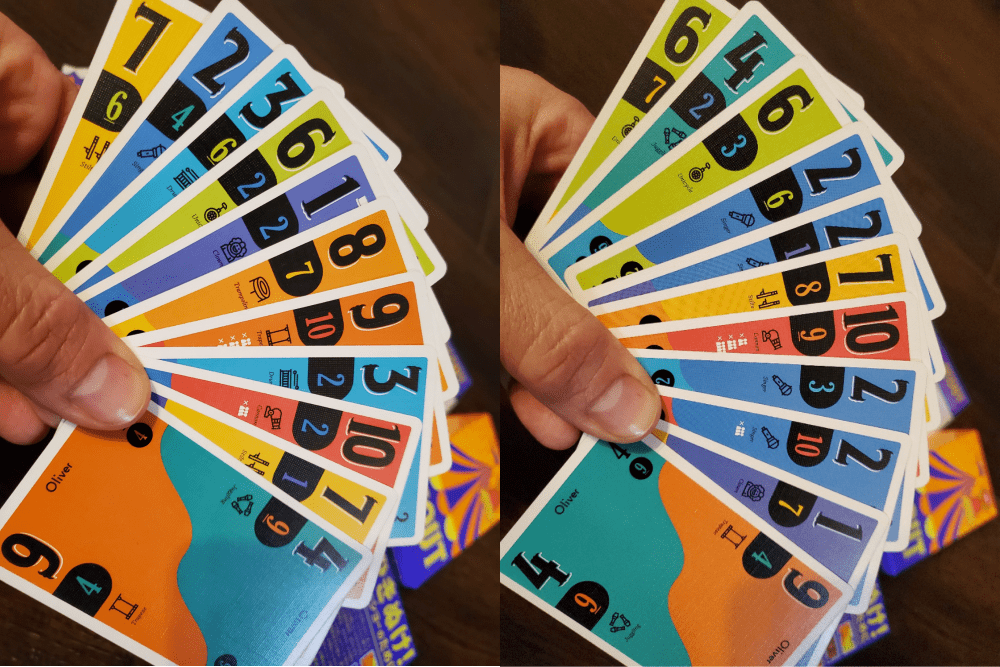

To begin each round, players are dealt the entire deck. Once the cards are picked up—and this is critical—players are not allowed to adjust the hand in any way, save for one decision at the outset: after looking at the lay of the land, players may turn the hand upside-down and use the numbers on the other side if they seem more favorable. Having unalterably chosen a side, play begins.

Players have two primary choices on their turn, plus a third choice that blends the first two. First, they may Show. Simply stated, this means laying down cards in either a set or a run sufficient to beat what had been played before. In the event they cannot or choose not to beat the previous play, they may Scout by taking either end card of the play that is currently in the lead. The lifted card may then be placed into the hand in any orientation, though after placement the card cannot be moved. Finally, once each round, each player may Scout & Show, blending the two in a combination full of showmanship and dramatic flair.

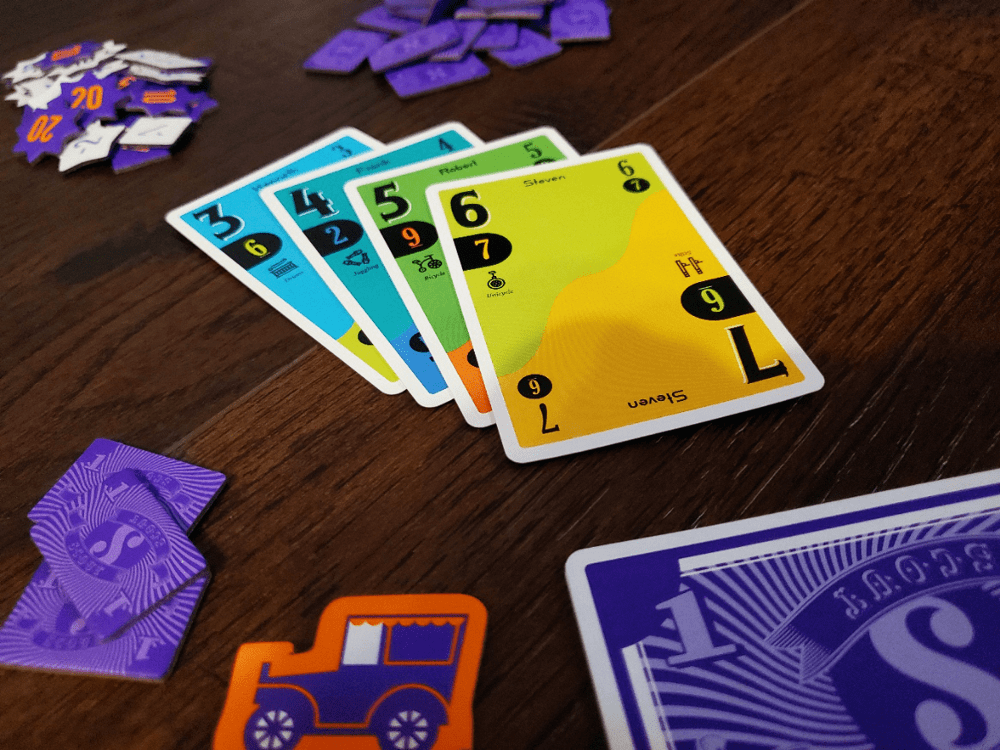

There are three factors that determine whether one play defeats another. Factor #1: More cards are always stronger than fewer. Factor #2: When the number of cards is the same, sets (multiples of the same card) always beat runs (consecutive cards by number order). Factor #3: When the number of cards is the same in a run, the lowest card of the new play must be higher than the lowest card of the previous play. When one player bests the previous lead, they claim the defeated cards as cash—a dollar a pop, so to speak—to score at the round’s end.

When a lowly circus card is Scouted away, the card’s owner receives a cash token, another dollar for their trouble, the other source of scoring in each round.

Play continues in this fashion until a player either lays down their final card or a previous play makes it all the way around the table without another player Showing something superior. The player who goes out loses no cash for cards in hand, while everyone else loses a dollar each. The earned cash is then tallied before the next round begins. There are as many rounds in the game as there are players, but as I’ve already stated, the number of players, and therefore the number of rounds, should always be four.

I’m not joking about the four player business

To put the game’s flow in perspective: say you’ve managed to gather a run of five cards, numbered three through seven. The second player, unable to best your effort, is forced to Scout the three, leaving a run of four through seven. The third player, also impotent before your mastery, Scouts the seven. The round then depends on player four, who Scouts the six, flipping it over as an eight in their hand, and then—having played a Scout & Show token—lays four eights to best your now-pilfered run of only two cards. Of course, in compensation for the three Scouted cards, you’ve received three bucks and you now look over your hand to see what you’ll do about those eights.

Consider the same scenario at three players: Having laid five cards, now only two ringmasters stand in the way of your solid run making it around the table. The rounds, as you can imagine, are much shorter as any solid play has a much, much better chance of returning to you unscathed. The three-player affair is all about who can build that pretty good run or set fast enough to catch the others off guard. Of course, such a reality also places a greater emphasis on the quality of the deal, which may unintentionally shift the game in someone’s favor.

At five players, the opposite is true. The quality of Show necessary to survive the table being so egregiously high, every play is Scouted and the round lingers on as players attempt to dwindle their hand while holding on to some multi-card play that will leave them without a card at the opportune moment. This places a high emphasis on effective Scouting and timing.

There is a two-player ruleset that allows each opponent to Scout a certain number of times in the round, thereby simulating a more populous group despite the human limitations, but I’ll not spend time on such an option.

At four players the full gamut of mechanisms is alive and well. It is entirely possible, occasionally, to play a hand so sweet and lovely that no opponent dares challenge it. It is possible to spend time intentionally Scouting cards because you know someone will surely beat an average play, just to assemble a gargantuan set that will bring the opposition to tears. It is possible to hold onto that gargantuan play an extra cycle or two because you know there will be a better moment. It is possible to play a slow round, tossing off the right cards at the right time, closing gaps in the hand, supplementing with the occasional Scout on the way to a thrilling finish. In short, the cards and the head games thrive in this sweetest of sweet spots.

There is an art to managing the hand in SCOUT. In reality, you want to be Scouted. You want those Scout tokens, so you make plays that you know won’t go around the table. You also want to get the big play to the table early so that others, who have not had time to offload their dead weight cards, get caught holding a load of negative cash. But as a round lingers because no one could pull off the early monster, you want to defeat previous Shows, claiming cards and cash on the way to a dominant victory.

I absolutely adore the nuance of the game.

For fun, I also adore referring to the cards by their circus names. Heck, I might even talk about Larry’s trapeze skills (he’s also a regular John Bonham on the drums) or how we almost lost Olivia (the juggler) last week shooting her out of a cannon. And don’t even get me started on Steven’s skills with the unicycle! When I take cards away, I want my neighbor to feel the pain of losing a valued performer. Honestly, you have to admire the attempt to make a theme of any sort work with a game like SCOUT. In a way, I don’t think it would be the same game without the big top. It’s absurd in the best possible way.

Bottom line: I am beyond tickled to add this one to my collection. If you have a foursome that either enjoys card games or each other, you don’t have to refer to the cards by name, but you should definitely be playing SCOUT.

Add Comment