Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

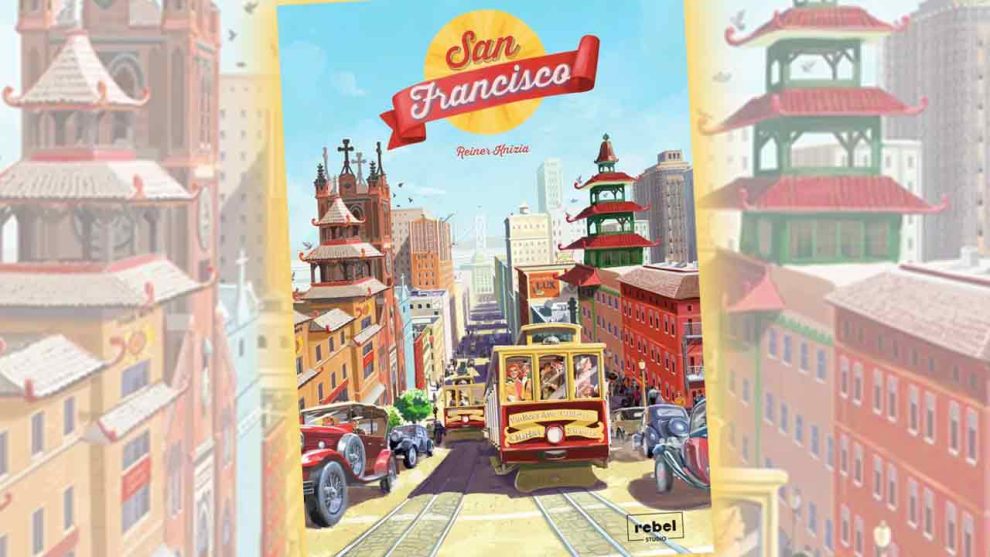

San Francisco makes me wish I had a podcast. Talking about this game would be much easier if I only had to do so for three or four minutes before moving on to other topics. The extemporaneous nature of the medium would be a real boon, allowing for improvisatory rambling. Alas, my chosen medium is the written word, so we have to do this properly. I have to organize my thoughts.

Location, Location, Location

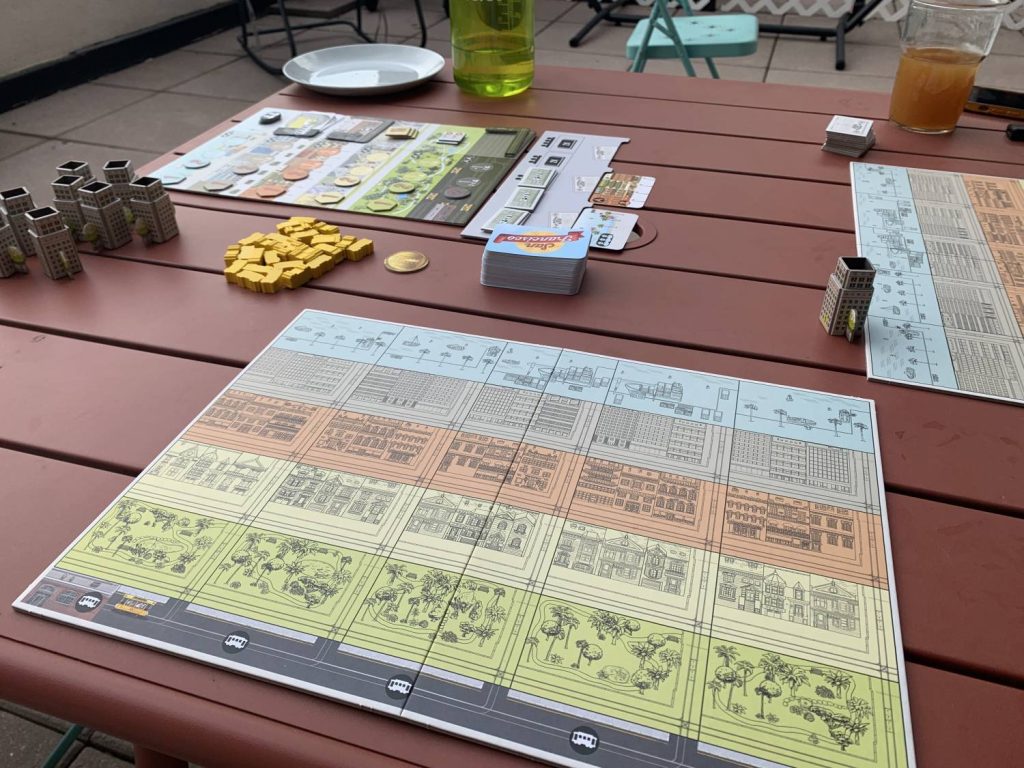

San Francisco is part tile-placement and part…I guess you’d call it an auction game? On your turn, you either take cards from the market or you take a card from the top of the deck and add it to the market. If you take cards, you’ll then have to immediately place the ones you want to keep on your player board, in an order of your choosing.

Though the order is up to you, where you place them generally isn’t. The cards you take are always placed in the leftmost free space of each row, and in which row they go depends on how they’ve been zoned. Green cards are parks. Orange cards are part of Chinatown. Black cards can go anywhere you like. That kind of thing. You choose which ones to immediately place, in what order you want to immediately place them, and which cards to discard.

There are some adjacency considerations you’ll want to keep in mind as you build. If you take a foundation card, you can only put a skyscraper on it if the orthogonally adjacent cards have a total of seven or more workers on them. Each skyscraper is worth 1 point at the end of the game, in a game where final scores are usually in the high 8’s or 9’s (there are half points). Adjacency also matters for your trolley network, since tracks are useless unless connected to a depot.

If my description makes the tile-placement portion of this game seem dry, that’s because it is. If it seems like I’m blowing through all of this information as quickly as possible, it’s because I am.

To Market, To Market

The market is where things get interesting. If you add a card to the market, you place it in one of three columns. Which of the three is entirely up to you. If you claim the cards in a single column, you take not only the cards, but a Contract token. What cards you want are immediately placed on your board, and the Contract token goes beside your board. Once you have one Contract, you can no longer take cards from any column with fewer than two cards. Once you have two Contracts, you can only take cards when there are three or more. You get the idea.

The game must start to drag something fierce, as players have to wait longer and longer to take cards, right? Worry not. The number of Contracts on the table is in constant flux. The rules dictate that at least one player must have no Contracts at all times. In a three-player game, if two players have Contracts and the third doesn’t, that third player doesn’t take a Contract when they claim cards. Rather, the other two players put a Contract back.

If you’re the only player at the table without any Contracts, you’ve got a lot of power. In that position, I’ve cultivated columns with safe numbers of cards so that they have more of what I want. As the player with the most Contracts, you can quickly find yourself in a frustrating position where there’s nothing on the table you can take, and your opponent(s) can take whatever they want, including their time.

If you’re the only player at the table without any Contracts, you’ve got a lot of power. In that position, I’ve cultivated columns with safe numbers of cards so that they have more of what I want. As the player with the most Contracts, you can quickly find yourself in a frustrating position where there’s nothing on the table you can take, and your opponent(s) can take whatever they want, including their time.

That doesn’t last for too long, though, since you’ll be adding a card on each turn. In games with three or four players, it usually doesn’t last more than two rounds. In a two-player game, though, it can get nasty. Like many Knizia designs, San Francisco is weirdly sharp at two, since he relies on player count to provide entropy.

The Shadow of a Great Idea

San Francisco doesn’t really work. The tile placement falls flat for the most part. The Contract system is fascinating, but it doesn’t live up to its potential. I feel like I’m seeing the shadow of a great idea rather than the great idea itself.

Maybe there are too many cards in too many colors. The rules allow for discarding cards you don’t want instead of placing them on your board, which promises a game where you’ll be picking and choosing, intentionally combing through your options until you get what you want. In practice, both because a large part of scoring is racing to finish the different rows and because the deck is so big, nobody does that. You can’t predict when something you want is going to come out, if it ever will. You take what you can get.

In five or six games, I’ve made two good moves. Both revolved around making a column more attractive for another player. The first time, I had two or three fewer Contracts than my opponent and wanted to give myself even more space to pick and choose. The second, I was the Contract leader and wanted to let some air out of the tires. That’s incredibly fun, that a player in either position might want to do that, but I was only able to do it because I happened to draw a card that would appeal to my opponents. The odds weren’t in my favor.

In five or six games, I’ve made two good moves. Both revolved around making a column more attractive for another player. The first time, I had two or three fewer Contracts than my opponent and wanted to give myself even more space to pick and choose. The second, I was the Contract leader and wanted to let some air out of the tires. That’s incredibly fun, that a player in either position might want to do that, but I was only able to do it because I happened to draw a card that would appeal to my opponents. The odds weren’t in my favor.

The overall problem with San Francisco seems to be that it doesn’t encourage you to play well. A game where players dynamically swap Contract positions plays out more or less the same as a game where nobody gets above one or two contracts. A player who is super-discerning about their tiles isn’t more likely to win than somebody who takes whatever comes up. This makes the game approachable, but it doesn’t make it particularly satisfying.

That doesn’t mean it isn’t worth investigating, though. Particularly if you’re interested in designs, and Knizia designs specifically. What I want is another design using the Contract system. There’s something really special there. I commented in my recent review of Longboard that Knizia excels in taking a neat mechanic and letting it shine by putting as little around it as possible. This time, I think, the neat mechanic got a bit crowded.