Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

I am a big fan of the publisher Devir (and more technically, the in-house Devir Games line), and I am increasingly falling hard for what I refer to as “medium box” experiences.

My definition of “medium box” gaming: a lot of game in a small box, something that you can play in about 90 minutes, possibly solo but certainly with almost any hobby gamer, in a physical package that is literally bursting with components paired with rich gaming experiences for a price that lands in the $30-$40 range.

Salton Sea (2024, Devir Games) is another of these medium box experiences. But by no means is it perfect. In fact, a full third of its mechanics feel extraneous to the point that I’m not sure I would attack that part of its gameplay if I was interested in consistently winning.

But Salton Sea nails the “medium box” mentality I seek with Devir products. Salton Sea has a manufacturer’s suggested retail price (MSRP) of $40. It plays solo, and the box is the same size as Devir’s other medium box games such as The Red Cathedral. And it has one mechanism that might already be my favorite gaming mechanic of the year.

Not the Val Kilmer Movie

The Salton Sea is a 2002 film set in the region of the same name in California, starring Val Kilmer as a guy whose wife suffers an “unfortunate accident” and has to navigate a seedy, tweaker-rich underworld rich with a cast of weird and wacky characters to find out what happened to his wife. When I saw The Salton Sea in theaters, I remember thinking how much it felt like a Quentin Tarantino movie…to learn later that it was not actually directed by Tarantino. The film is full of little twists and turns, and if you can find it on streaming, it is worth a look.

The game Salton Sea is a 1-4 player, economic hand management and worker placement Eurogame that plays in about 45 minutes per player. After my first two-player game, I canceled plans for a playthrough with a larger group. Four players trying Salton Sea is not recommended, as nothing about the game’s core gameplay changes, and downtime in a game with very little interaction is a killer.

The game, like the film, is worth a look because there are so many little twists and turns during each play thanks to the game’s hand management requirements.

The Salton Sea—the actual, real-life area in California—is a region where geothermal energy is apparently easier to harvest than other parts of the world. The game features commercial land acquisition, drilling, brine extraction, energy processing, and the sale of the resulting product to market.

Sexy, it is not.

The business aspects of the game comprise about a third of the experience—selling this product to market raises the share price of one of the game’s three unnamed companies (so let’s go with red, blue and yellow), while trading it through business deals provides profits to other unnamed entities. Players are also chasing Euro-style public milestones while trying to score the most points.

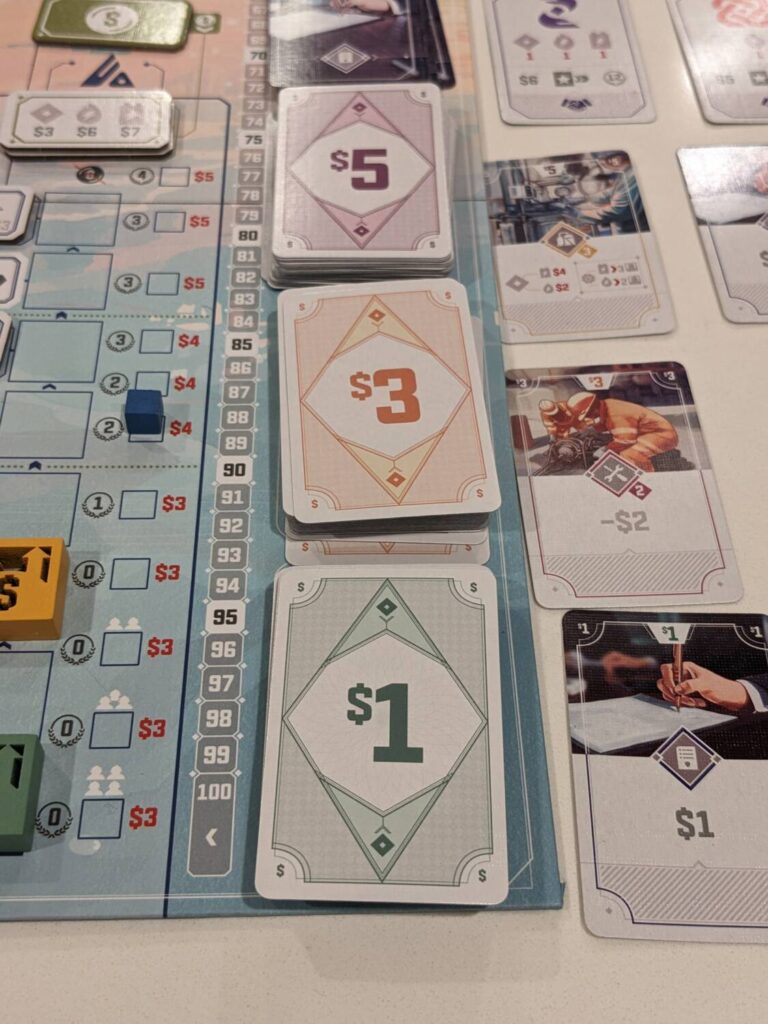

Salton Sea boils down to three different mini-games, all tied together in a shockingly easy-to-teach package. The first, and best, of those mini games is the hand management element, because cash in Salton Sea is represented by action cards valued at $1, $3, and $5.

Each action—such as buying shares, drilling, and claiming new brine-rich territories—can be found on both a player’s personal board or on the action cards. You begin the game with $7, all in $1 cards. The actions on the cards are the same as the ones on your board, but the actions are always better on the cards. This usually means a minor internal debate on what you are willing to do each and every turn.

“I could take the drilling action on my player board to drill one level deep, or do it with my $1 drilling action card, which lets me drill two levels deep,” you think to yourself. “Or I could spend that $1 card to take a research action for a new card that costs a buck, which lets me get a share of the red company but then I’m out of cash for a couple turns…”

It was shocking how many turns I took where I could not figure out what to do, because cash was tight—in a good way—and I wanted to optimize my turn. Even though the game has a dozen actions, not all of those choices are available to you every turn. (For example, you can’t process brine when you don’t have any, and you cannot advance your business development marker if you don’t have at least $3.)

Even during my first play, Salton Sea quickly moved to the upper echelon of my favorite hand management games of the recent past, such as two of the best games I played in 2023, Hegemony: Lead Your Class to Victory and Voidfall. The fact that the $3 and $5 cards are so much better actions made Salton Sea shine. You really want better cards, but eventually you are going to wrangle with your emotional state as you spend your $5 card (with the massive share purchase discount!!) to process energy on a later turn.

Part of my love for this mechanic is scarcity—you could begin a turn with no cards (i.e., no money) in hand. But even with a small hand, you will find yourself torn over whether to get rid of even a $1 card, because $1 card actions are still pretty decent, like getting a dollar off of a new land claim card, which is required to do more drilling for brine. Watching players spend can be agonizing, in part because you just went through the same exercise, but also because it slows the game down. (We’ll come back to this last part.)

The other part of the game I found interesting was the push/pull of warehouse expansion (to store more goods), unlocking more workers, and how to advance the track where these two things happen: the business development track. A large star token moves slowly forward on a track in the middle of each player’s personal board, and because of the reward at the end of this track—a bonus point for every star on achieved public milestone cards—I really can’t see a way to win Salton Sea without significant investment on that track. The track also moves through completed contracts and even completed land claim cards as a bonus listed on specific claim cards.

So, if I’m breaking Salton Sea into thirds: the first third, the hand management, is great. Often, it is spectacular. The best games make moments like the hand management tense and challenging, and Salton Sea certainly achieves that.

The second third—the business of moving from land squatter to brine, to clumsily borrow a reference from a higher power—is fun too. The process of moving through claim cards, to drilling, to extracting brine, to deciding how to best utilize processed energy, either via sale (for cash cards, super valuable) or contract completion (less cash, but usually a bump or two on the business development track as well as victory points)…all of that is great.

But the final third of the game keeps Salton Sea from achieving greatness…the stock market. This won’t stop me from recommending the game, but it is a significant bump in the road.

Salton Sea’s stock market is a Chicago pothole. You need to put a cone in it to make sure everyone sees it…and, as long as you don’t ride your bicycle into it, you’ll probably be just fine.

My Vote? Blue

Salton Sea allows players to process brine into lithium or geothermal energy. Geothermal energy is valuable, but lithium is a bit more valuable in the marketplace. It costs more to make lithium, but the yield on some of the game’s lithium contracts can be massive, giving players a juicy choice or two when processing brine.

When selling any of these three products to market, the active player takes the sell action to sell an item to one of the three companies mentioned earlier. Selling to a company yields a price listed at the top of the column where a token shows the current prices for each item.

Problem #1: almost every token’s price range lands in the same place. Brine is almost always priced at $3. Geothermal energy, $6-$7. Lithium, $8-$9. But the market is supposedly random, and moves every so often as a company’s share price rises. So even when the market changes for, say, Blue Company, the price difference is usually not enough to warrant selling to Red or Yellow.

Why does share price matter? Because as shares get pricier, individual shares rise in price and become more valuable for shareholders in terms of victory points. So, investing in a company by buying its shares then selling only to that same company makes sense.

But then problem #2 arises: only one company in the game seems worth investing in, and that is Blue Company. That’s because every Blue share you have purchased after the first one yields a very handsome bonus: either a bump on the business development track (which may unlock more workers) or a profit-sharing tile, the game’s way of rewarding a shareholder with a one-time-use action tile.

With Red Company and Yellow Company, the bonuses don’t start until much higher on their respective tracks, AND Red/Yellow shares are worth less at the end of the game. In fact, players have to collectively bump the Red Company share price 4-6 times (six times in a four-player game, for example) to even have a single share of Red be worth a point. That means that unless you are invested in Red, you don’t really care who you sell to if the goods prices are the same, because you will sell lithium to whoever is paying the most at any given time.

Plus, there are less bonuses on the Red Company and Yellow Company tracks. It always felt like a player would lean towards buying shares in Blue Company, despite the higher prices.

I really wish the design of the stock market was different. What if shares in Red Company kept prices and bonus locations intact, but offered crazy-high-level bonuses? What if each company had a different focus on bonuses—maybe Red is all about processing bonuses, and Yellow is all about drilling bonuses, etc.? What if workers could only be unlocked on the stock market tracks instead of the business development track on each player’s personal boards, to incent players to buy shares?

I’m sure designer David Bernal considered all these things, and maybe some of the elements of the stock market changed during the development of Salton Sea. No matter what, the end result is disappointing because I think the stock market is not a viable path to victory if players only concentrate there. (I’m not even sure it is possible to focus only on the stock market, based on how tight cash is here. But if you are gonna buy shares, you are buying Blue Company stock, full stop.)

As a huge fan of economic games, I really wanted this part of the business building to shine in Salton Sea. Unfortunately, it does not.

So, Stick to the Drilling

Salton Sea works everywhere else, so future plays will definitely feature my pursuit of building my business around the quick expansion of my worker pool, my warehouses, and earning cash to expand my options for middle-to-late game turns.

Devir—as usual—nailed this production. The rulebook has a nice economy to it, and almost everything is clear. (The Buy Shares action left us wondering about how shares might be scored, but assuming each bump on the track is one share led scores to land in the 65-to-85-point range, which felt right for a Euro of this type.

Even better: the double-sided player aids. Oh my goodness, they are all I need. All the game’s main icons are there on a large tarot card—THERE’S ONE FOR EACH PLAYER!!!—and each icon has a page number where players can go to read more about each specific action in the main rulebook if they have additional questions.

I thought this move was brilliant, and led to multiple circumstances during my first three games where I looked at the player aid, referenced the rulebook, then went to check out a rule to make sure I had it down pat.

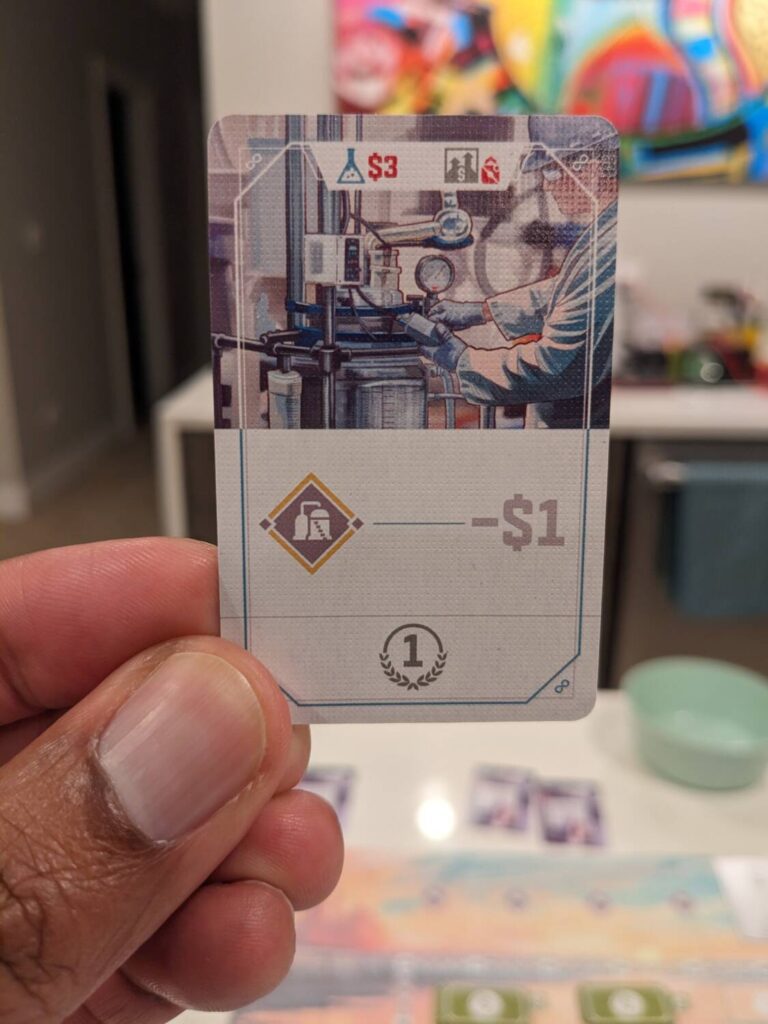

Another quality of life winner: the cards that can be used to take actions have a striped grid at the bottom of each card for a player to place their worker on the card. Play the card in front of you, place a worker. Other cards, like contracts or research cards, often don’t have that area at the bottom. Some research cards do have that striped grid because they are action cards for one-time-use.

I didn’t have to answer any questions about what cards could be used for actions during my plays. Bravo, everyone involved in designing and producing this game!

I love the share tokens as well as the individual wooden components and the player boards. Contracts and research bonuses have a nice holding place, and the entire board feels like it builds outward in a comfortable way. This does mean that each player will need space for all their stuff, despite a very manageable main board size. (The other space challenge is the market of cards available for pickup when players need to cash in or grab new contracts and research cards.)

Upkeep is reasonable thanks to the game rules around cards taken from the market—no new cards come out until the next round. The game end trigger is also easy to parse: when the deck of land/claim cards runs out, or if two companies reach their max-level share price, the game ends at the end of that round.

But the reason I will come back to Salton Sea is the hand management. It’s tense. It’s especially tense when you realize you are out of cards, or when you want to do something that requires a single dollar more than you have. Deciding which cards to spend has that nice Race for the Galaxy/San Juan feel, too…I could spend this card as money/goods, but what if that card never comes around again?

As a one- or two-player game, Salton Sea is highly recommended, save for the investment mechanic described previously. By my final play, I usually found myself buying shares of Blue Company late in the game once I knew the value of what shares might look like, as well as grabbing some bonuses that helped push my business development track to the finish line.

Juicy decisions in a small package? Sign me up. Devir continues its stellar run of releasing medium box games; add Salton Sea to the likes of 3 Ring Circus and The White Castle. I can’t wait to play whatever comes next!

Add Comment