War of the Woods

Let’s set the stage. The longstanding oligarchal Eyrie Dynasty (a flock of birds) has fallen apart due to infighting and internal strife, leaving a power vacuum in the Woodland. The nefarious Marquise de Cat has seized power and begun chopping it down for fun and profit. But enough is enough…the denizens of the forest lived under the oppressive Eyrie but are now seeing a different kind of oppression from the Marquisate. They’ve joined forces to form the Woodland Alliance, hellbent on taking back the Woodland. Of course, war means a boost to the economy, and the Vagabonds skulk around the forest, wheeling and dealing with all sides to turn a quick profit.

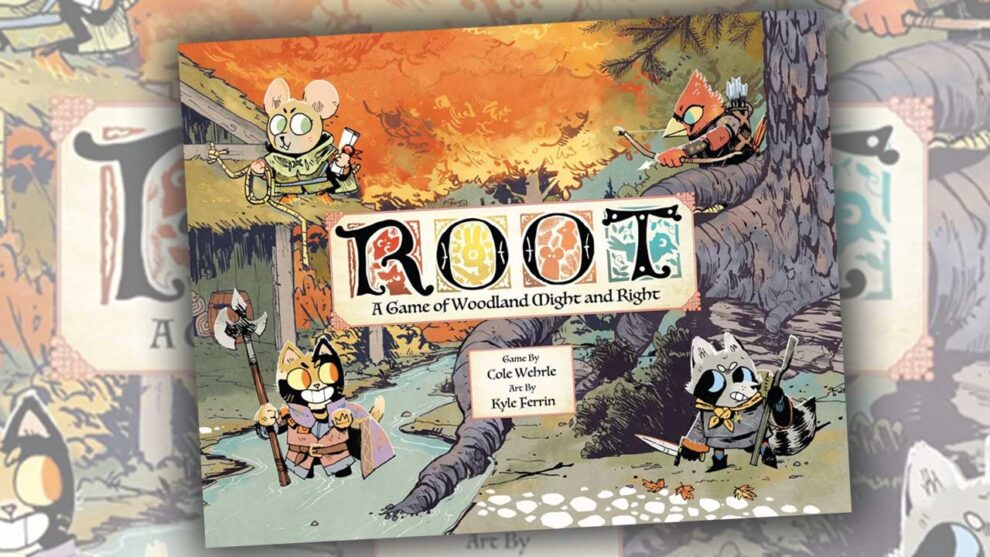

In Root, players will take control of one of the four adorable factions vying for control of the Woodland in a race to score 30 victory points. These factions are brought to life by the impressive artwork by Kyle Ferrin but take inspiration from real-world historical entities. Cole Wehrle made those influences obvious during his wonderful designer diaries. Throwing a cutesy woodland critter coat of paint over everything makes the theme easier to digest, for sure, and adds a whimsical charm to the game. But at its core, the game is an examination of power structures and systems of control that exist among certain types of real-world states, something that will delight anyone with even a passing interest in political theory.

Root is an asymmetric game in which every single faction is different in their actions, strengths, weaknesses, and how they win. Each player will go through the same phases on their turn: Birdsong (morning), Daylight (afternoon), and Evening. However, what actions they take during these phases will vary wildly between factions. Truly, learning a new faction in Root feels similar to learning a new deck in something like Magic: the Gathering in that it will likely take several reps to learn what is optimal. This means Root has a pretty steep learning curve, and your enjoyment may depend on how much it can hit the table.

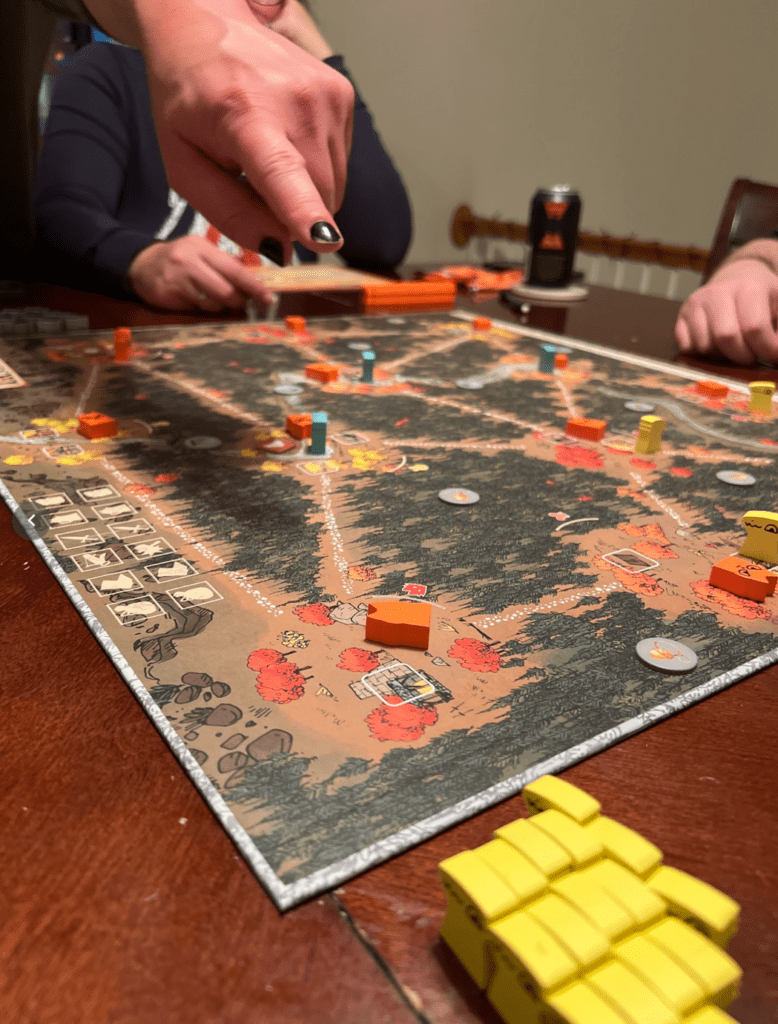

If digital implementations are more your speed, you can check out Meeple Mountain’s review of Root Digital. I own both the physical and digital versions and play both for different reasons. When playing solo, I prefer playing the digital version rather than using Root’s Clockwork modules that add “AI”-like NPC factions to the physical game. The digital version also features challenge scenarios to win with alternate rules. Overall, though, I much prefer the physical version. It has such fantastic table presence with its bright, illustrated meeples and lovingly handcrafted art style that it’s a no-brainer for me.

Furry Fury

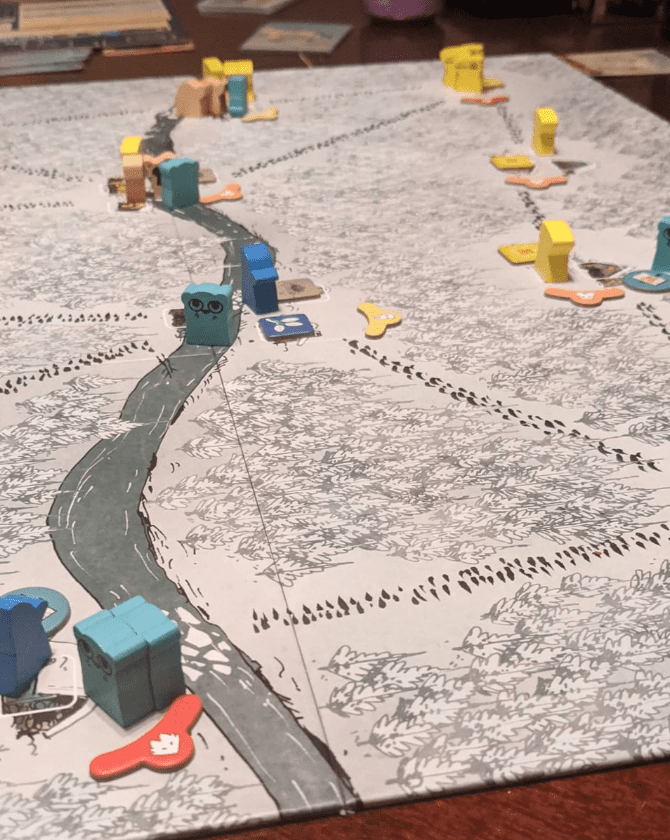

Despite the gaps in player experience from the asymmetrical gameplay, some core things unite the experience. The board is made up of a series of clearings connected by paths and separated by forests. Each clearing has at least one space to build a structure (square tokens), though some have two spaces, or have an optional space that can be uncovered by the Vagabond. The clearings all have “suits” on them, which in Root are represented by rabbits, foxes, birds, or mice. These are important because the deck of cards included in the game interacts with specific clearings based on suits.

The deck of cards each contains a suit and, usually, an effect you can “craft”. Each faction crafts cards with different mechanics, but they are usually tied to the suit on the clearings you rule. Crafted cards can give you powerful static effects such as extra move actions each round, victory points, or allow you to play a surprise ambush on your opponent during combat. But this is not a deckbuilding game! As you gain cards, you’re expected to spend them pretty frequently to advance your agenda. Not only do the cards matter for their actual effects, but most factions have a way to spend cards as resources in pursuit of their goals.

Outside of crafting, all factions have access to a way to move around the board and initiate battles. Unlike many combat-focused games, it’s worth noting that having two opposing factions in the same space doesn’t automatically trigger combat. It takes a specific battle action to start combat. Combat is very simple in Root – you take two combat dice and roll them. The attacker claims the higher value, and the defender claims the lower. They deal that many “hits” to the opposing side, removing that many units. Some cards may give extra hits. If all warriors are gone, then the hits can take out enemy structures in the area, and attackers score victory points for each piece of cardboard removed from the table.

Choose Your Fighters

The crux of the Root experience lies in its vastly varied factions. Each one plays completely differently, and would take a whole separate review series to cover the nuances of each one (especially when you start getting into the expansions), but for the core box, there are four primary factions to choose from.

The Marquise de Cat

The Marquise de Cat are the current faction in charge of the Woodland, so they begin the game spread out all across the board. They have a Keep, which allows them to revive warriors lost in combat back at their home base. Generally, they have a pretty linear scoring progression, as they use their three actions per round to spread out and build recruiters, sawmills, and workshops. Recruiters let them pop up warriors in new places, sawmills are the economic engines that let them pay for more buildings, and workshops allow them to craft cards from their hand. They score victory points for each building they place, making their gameplay style less about direct conflict (though that happens when needed) and more about expansion, expansion, expansion.

The Eyrie Dynasty

The Eyrie Dynasty, by comparison, has been reduced to one small corner of the map. They seek to regain lost glory by retaking the forest bit by bit. They score by placing roosts on the map and getting more points per round as they increase the number of roosts in play. Perhaps most uniquely, the Eyrie don’t have complete control over the actions they take. They have four actions that must be taken in order: recruit, move, battle, and build. On their turn, they can add cards from their hand to the action tableau, but those cards are then locked. Each turn, they must add more cards and be able to perform all actions in order. They fall into turmoil if they cannot perform an action (e.g., they have a fox card under “battle” but no enemy units to fight in any fox clearing). Their whole tableau goes away, and they lose some victory points and must start fresh in the next round. The Eyrie requires careful forethought and preplanning to make sure you’re able to perform the actions you need next turn, and the turn after that, and the turn after that, almost like coding a computer program that has to be able to run each line every time successfully.

The Woodland Alliance

The Woodland Alliance are the underdog upstarts of the forest who have to spread sympathy to turn people into supporters for their cause. Because they’re the underdogs, they get to break the rules of combat and use the higher die on defense, and whenever another player marches into a sympathetic clearing or removes a sympathy token, they have to pay a card for causing outrage among the commoners. They have a stack of cards called “Supporters” that they can spend to cause revolts in clearings or spread sympathy to nearby clearings. They can train officers once they’ve revolted and built bases in clearings. As they get more officers, they can take more actions in the Evening phase, letting them recruit more warriors or fight more battles. The Woodland Alliance starts off slow, as most rebellions do, but gradually builds into a louder and louder crescendo if the dominant factions don’t stomp out the rebellion in time.

The Vagabond

Finally, the Vagabond is the most unique faction in the base game. While everyone else is playing at war, the Vagabond is slinking around the forest, playing the economy. The Vagabond is a lone pawn and does not have warriors like the other factions. As other players craft cards for victory points, they’ll also craft items that the Vagabond can acquire from them through trade. The Vagabond’s capabilities are directly tied to what items he has acquired, as they can affect his carrying capacity, what actions can be taken, how much damage he can inflict, and more. The Vagabond can also go on quests, moving to clearings and exhausting items to fulfill certain requirements and score victory points. While everybody else is fighting and expanding, you’re the only player who can move through the forest itself, not bound by the clearings and pathways in between. There’s even a friendship mechanic where you can raise your relationship levels with certain factions, gaining victory points when you do. But if you ever kill an enemy warrior, they become hostile to you, and while you can no longer trade, you now get points for taking out their units.

Beneath the Canopy

I’ll bet that all sounds overwhelming. You’d be mostly right! For the first few plays, you’ll be mostly figuring out your own faction and what they do and won’t be too concerned with how the others play. Root is definitely not a game you want to play once and then revisit six months later. But if you’re anything like me, by the time you finish your first game, you won’t be able to resist immediately wanting to run it back.

There’s an almost infinite amount of replayability in Root because of its inherent design choices. By making each faction so wildly different in terms of gameplay and win conditions, there’s an obvious compelling reason to want to play over and over again so you can learn each faction. Once you’ve played them all, you’ll better understand how they play and, better yet, how to stop them from winning. But that’s just the surface of it all. This is the type of game that can hook its claws into your brain and consume your thoughts. After my first play as the Eyrie Dynasty, I spent days pouring over possible opening moves in my head. “What if I intentionally went into turmoil as early as possible?” I thought. And on my next game, I did exactly that. It took many reps with those darn birds to understand how to build an efficient economic machine, but the important thing is that on every single play, I learned something new about my faction or learned a new interesting interaction or strategy for how to fight another faction.

Better yet, each player brings a completely different playstyle to their preferred faction. If I’m on the Eyrie Dynasty, I’m likely to play an explosive expansion strategy early, making the spots near me more dangerous. However, if one of my friends gets the Eyrie, he likes to slowly expand and thus can be safely ignored by the other factions for a bit longer. There’s so much room for nuance and depth in Root that it exhausts me to even try to write about all of it. Root is not a game you just dip your toes into, at least not for me. It’s a game that invites you to keep peeling back layer after layer, discovering new combinations and strategies to implement in the next game, and the next game, and the next game.

Is It Really THAT Good?

As a caveat, as with any game that requires multiple playthroughs to fully understand, there’s the potential for games to be remarkably lopsided as everybody learns how to play. In early games of Root, it is highly likely the Vagabond will win more games than average because the faction is so different that most players don’t see the value in attacking it. After all, it’s just a little furry guy trying to make a quick buck! What’s the harm in that? It takes several games of seeing the Vagabond in action to realize that it behooves everyone to take a few swings at the guy if given the opportunity to slow down his economic engine.

That is to say: the factions are not inherently balanced, which may not appeal to people who want a perfectly balanced experience. The balancing comes from players understanding each faction’s strengths and weaknesses and knowing when to push and exploit them. Left unchecked, some factions can completely steamroll the game, and other factions may feel like they never had a fighting chance because they didn’t know to team up at certain points to slow them down. The information barrier to even being decent at this game is staggeringly high.

That’s not to mention the plethora of optional content out there, like the multiple new expansion factions, or the variant maps that change up gameplay, or the Clockwork expansions that enable automated NPC faction play to spice up smaller player counts, or the optional Advanced Setup (AdSet) for more competitive games, or the half-dozen variants for the Vagabond, or the hirelings that grant additional actions, or landmarks, or the tabletop RPG, or… or… or…

You see my point. It can be overwhelming. If you want to get the most out of Root, you have to be willing to put in the time to learn. That means several learning games and being willing to lose as long as you learn something from it. I’ve shown the game to people who haven’t loved it, and they’ve cited information overload as their primary reason for not enjoying it. That’s totally fair. Root is a lot to take in. Despite my dozens of plays, I still learn new things every time I play. At the highest levels of competition, it asks a lot of its players to understand their faction while also being able to analyze how close other factions are to winning. That can all be daunting for a new player to take in. That’s why I recommend taking things slowly and concentrating on one thing at a time.

But for me, it was love at first play, and that was just a taste. There’s so much more content out there that you could make Root the only game you play and still never get bored or run out of new things to try. It’s everything I want in a game! Asymmetrical factions, room for negotiations and betrayals, and thrilling economy-building… oh my! Cole Wehrle nailed it with this one, to the point where anything with his name on it is an instant blind purchase for me. Even as more and more games arrive at my house and clutter my shelf and other games get sold or traded away, there’s one precious, sacred shelf for all my Root content that dares not be touched. It has earned its place on the throne.

Excellent review! And this is about my experience — Root is fantastic! And it will take a long time to master…

The four factions in the base game offer a different flavor for player because of the asymmetry, and the subsequent factions included in the expansions greatly expand on the possibilities. For those interested, the digital adaptation on Steam is a excellent way to hone your skills, and includes all the factions and Vagabond variants up to and including the Underground expansion. Hopefully, we’ll see the Marauder factions (Lord of Hundreds & Keepers of Iron) sometime this spring…

Agreed! I love the digital implementation and am waiting for the Marauders faction as well. I’ve been trying to slowly grind through all the challenges. Some of them are VERY hard.