Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

The cooperative games that I come back to time and again are consistently those with heavy communication restrictions. When done right, encumbrance leads to moments of discovery, as the players discover the sorts of creativity that only exist in the presence of narrow parameters. Much as Japanese poets find remarkable beauty in seventeen syllables, so the arc of an entire round of The Crew can be indicated with a single card. Restrictions breed innovation, exploration, and discovery. Without walls to bind us in, we have nothing to push against.

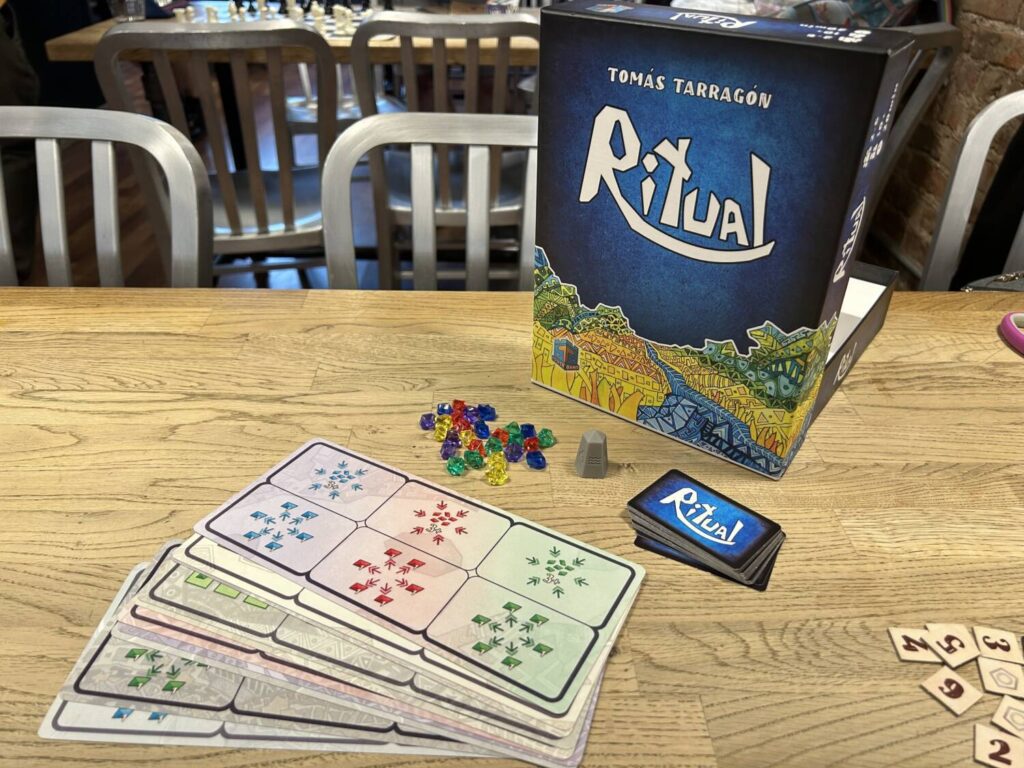

The restrictions placed on you by Ritual, a cooperative game from designer Tomás Tarragón and publisher Strohmann Games, are near-total. It is meant to be played in complete silence. Your only means of communicating is indirect, implied in the action you choose to perform each turn.

Each player begins the game with four random gems and a card. The cards show some combination of gems: five in a single color, three each in two different colors, or two each in three different colors. In order to progress through the round, players have to help one another collect their sets by making smart use of the actions available: Take a gem from your left; Pass a gem to anyone else; Place a gem on the placard that indicates you would like someone else to exchange it with a different-colored gem in the middle; or exchange someone else’s.

Through those four actions, you learn to communicate. Nabbing a gem from your neighbor is a clear signal to everyone else that you need that color. Placing a gem on your placard says the opposite. This is straightforward enough, and to be honest, it doesn’t sound that appealing, does it? Thank goodness there are a number of complications that render all of this murky.

For one thing, the number of gems in play is entirely fixed. There’s a pool of extra gems in the middle of the table, and you can swap one color out for another, but the quantity of available gems never changes. In a six-player game, there are 24. Some quick back of envelope math tells us what players only realize after a few minutes of constantly eating away at their own progress: there are not enough gems for everyone to collect their set. This is not inherently a problem, because you only need three players to succeed in order to move on to the second stage of the game, but it requires humans to do something that does not come to them naturally, especially in gamic environments: you have to be selfless.

The necessity for certain players to forgo their dreams is compounded by the timer. You have a limited amount of real-world time in which to do everything. At the easier difficulties, it’s seven minutes, but that goes by quickly. Once three players have successfully collected and revealed their sets, you move on to the next stage, in which the table as a unit has to accomplish one of six possible final goals, known only to a single player.

In the earliest levels, these goals are simple enough: each player has to have exactly one red gem, or all of the blue gems have to be with a single player. Later levels get incredibly difficult. The absurdity of them doesn’t communicate well to people who haven’t played the game, but my table found incredible mileage out of reading through the future levels after our first play.

Once your group manages to run the obstacle course, getting three players their sets and then completing the final goal, you get to experience the uniquely heady thrill of telling them that there are two more rounds, that each round includes an additional final goal, and that those goals have to be accomplished in a specific order. The stepwise ratcheting up of difficulty—one final goal, then two, then three—allows players to find a groove, settling in as the game gets sweatier and sweatier. By the time you get to the end of the third round, players are preparing ahead of time, setting up the next goal before the current one is even finished.

It is exhilarating to develop an entirely new way of communicating with other people. That’s what Ritual gives you. It doesn’t always work. Like any form of communication, there are bumps and inconsistencies. The means of communication that are open to you flat-out don’t make sense to some players. Ritual often relies on inference and implication, particularly when the current state of play doesn’t come close to lining up with what people need. My first game was with a table of strangers at Essen 2023, including Tarragón himself. The other four players were friends with one another, and one of them never got it. In seven minutes of playing, he would consistently miss cues, or undo progress, thinking nothing of it.

That is absolutely part of the fun.

I have been playing with a first edition of Ritual, published by Tarragón’s own T-Tower Games, and the only shame is that it is entirely incompatible with colorblindness. The new edition from Strohmann Games takes some steps in the direction of addressing that, by choosing gem colors that can be more readily differentiated and cards that players can use to separate their different gems.

Tarragón’s two published designs share a preoccupation with language and communication. His first game, Blabel, required players to develop their own distinct languages in real time. In its way, Ritual is no different, though now the language is a mutual one, consisting of actions rather than syllables. I hope he continues to plow this furrow. He has hit on something wondrous.

Add Comment