Hello and welcome to ‘Focused on Feld’. In this series of reviews, I am working my way backwards through Stefan Feld’s entire catalogue. Over the years, I have hunted down and collected every title he has ever put out. Needless to say, I’m a fan of his work. I’m such a fan, in fact, that when I noticed that there were no active Stefan Feld fan groups active on Facebook, I created one of my own.

Today we’re going to talk about 2013’s Rialto, his 17th game.

Rialto is an area control game that is governed by an open drafting mechanic. The game is played over the course of six rounds, which are divided into a number of different steps. Central to the game is a deck of cards featuring cards corresponding to these steps. Each step serves a different function within the game such as jockeying for turn order position, adding councilmen to the city’s districts, and influencing the overall point value of the districts.

At the start of a round, several sets of randomly drawn cards are created and players take turns choosing one of these sets to take control of for the remainder of the round. Then the round is played out, step by step. As each step is played, the players will take turns playing a number of cards from their hand corresponding to the current step. The number of cards played will determine how effective the current step is for them. And, if they manage to play more cards than everyone else, they will also receive a bonus. At the end of the game, each district of the titular city is examined to determine who has the majority of their councilmen present, which will earn that player points. Other players with councilmen in the district will score lesser amounts of points based on their ranking. These points are added to any points the players may have scored during the game and the player with the highest total at the end wins.

Of course, this is a very high-level overview of the game. If you just want to know what I think, feel free to skip ahead to the Thoughts section. Otherwise, read on as we learn how to play Rialto.

Setup

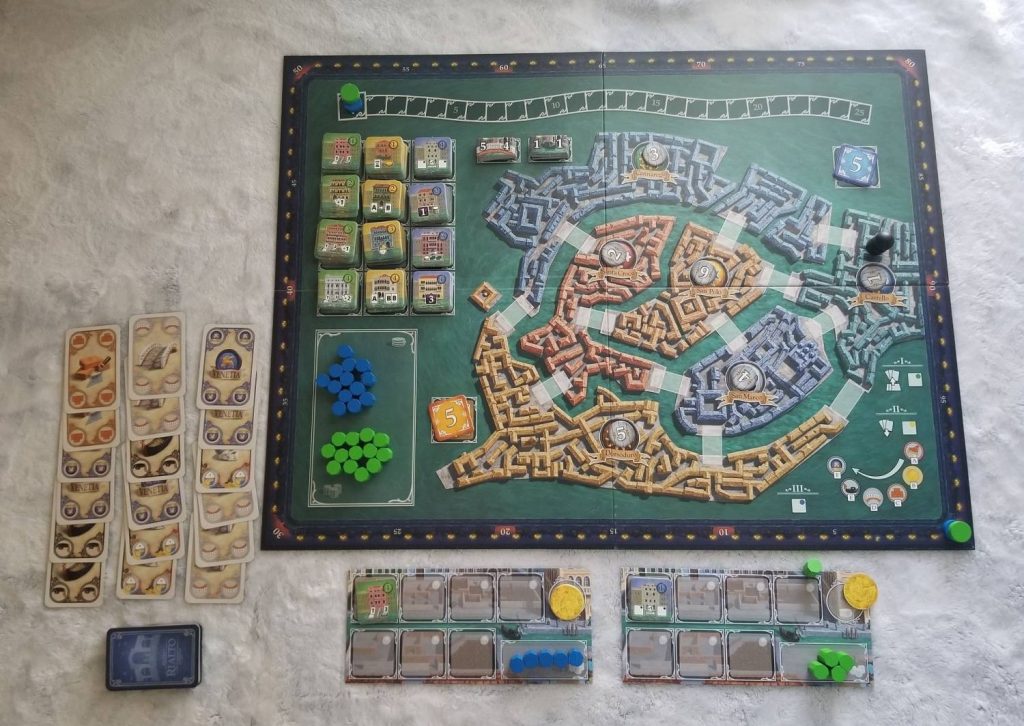

A game of Rialto is set up thusly:

First, the game board is laid out and the Round tiles are randomly placed into different districts. The Bonus tiles are placed into their locations. Next, the Building tiles are divided by color and cost and placed onto the board in same-colored rows, from lowest to highest cost. Shuffle the Bridge tiles and stack them onto their marked location. The Gondola tiles are stacked and placed next to them. The District token is placed into the district with the ‘1’ in it. The cards are shuffled to form a deck and kept, face down, off to the side.

Each player receives a Player board along with the Councilmen and counters in their chosen color. One counter is placed onto the first spot on the Doge track running along the top of the game board. The other is placed onto the zero space of the Score track. The players keep five of their Councilmen in front of them and the others are set aside in the storage space of the game board. The coins are kept here as well, but each player will receive at least one of these depending upon their position in turn order. Players also begin the game with a Building of value 1.

Turn order is important in Rialto. As such, it is likely to be hotly contested. During setup, the rules direct you to randomly determine who goes first. In my games, I just gather up all of the counters from the Doge track, shake them up in my fist, and then let them drop out one at a time. The first player goes on top of the stack with the other players placed beneath it in turn order.

When determining the player order in the future, the player furthest along this track will be first. If two players occupy the same space, the person whose marker is on top of the stack will be ahead of whoever’s marker is beneath theirs. And it’s worth mentioning here that the player positions on the Doge track are how ties are broken in the game.

Regardless of how you go about it, once you’ve determined the player order, you’re ready to begin.

Anatomy of a Round

Each round is divided into three phases. In Phase 1, the District token will move, the players will receive new cards, and green buildings will activate. To activate a building, a coin must be placed on top of it, and a single building may only ever have one coin placed on it at a time. In Phase 2, the players will be using their cards to do things and yellow buildings will activate. In Phase 3, blue buildings will activate. When the round ends after Phase 3, any coins used to activate buildings are returned to the supply. Any cards not played out of a player’s hand during the round may be kept for the following round.

Phase 1:

Green buildings may be activated at any time during this phase.

-move the District token to the next numbered district (move from 3 to 4, for example).

-create new card rows by drawing and laying out six cards per row, creating a new card deck from the discard piles (more on this later) if need be

-in turn order, each player selects a row to take into their hand, along with two cards drawn from the top of the deck and any cards they may have kept from the previous round

-after all players have selected their rows, they will reduce their hand size to seven, discarding any unselected cards into their own personal face down discard pile

Phase 2:

Yellow buildings may be activated during this phase at their appropriate times.

Phase 2 is broken into six different stages. In each stage, the players will play any number of cards from their hand matching the current stage (including Joker cards, as long as the Joker card is accompanied by either a card of the matching type or another Joker). The person that plays the most will perform the stage’s action and receive a bonus—as well as lead off the card play for the next stage. The stages are:

- Doge – move 1 step along the Doge track per card played (bonus: 1 extra step).

- Gold – collect 1 coin per card played (bonus: 1 extra coin).

- Building – take a building from the supply equal to or lower than the total of the number of cards played (bonus: add +1 to the number of cards played).

- Bridge – earn 1 victory point per card played (bonus: +1 extra victory point AND play the next Bridge tile between any two districts that do not have a tile between them).

- Gondola – move 1 Councilman matching your color from the general supply to your personal supply per card played (bonus: place a Gondola tile between any two districts that do not have a tile between them. Then place a Councilman into one of these districts. If you are the first person to have Councilmen in each district in one of the two district groups, then you receive the five point bonus).

- Councilman – move 1 Councilman from your personal supply to the current district per each card played (bonus: +1 extra Councilman may be placed).

Phase 3

Blue buildings are activated during this phase.

End Game

The game ends at the end of the sixth round. Then final scoring is performed. Players earn points for half the value of the total number of leftover Councilmen and coins in their personal supply (rounded up) and points from each of their buildings. Then the districts are scored.

For each district, add up the values of all of the Gondola and Bridge tiles that are part of the district. The full value of these is awarded to the player who has the most Councilmen in the district. The second place person earns half of this amount, rounded down. Third place earns half of whatever the second place earned, rounded down. And fourth earns half of whatever third earned, rounded down. The player with the highest score wins. If there’s a tie, whoever’s furthest along the Doge track breaks the tie.

Thoughts

Prior to playing Rialto several times in preparation for writing this review, it had been a few years since I’d last played the game and I couldn’t remember the specifics of just why that was. All I could recall was a vague recollection of a weird mix of liking the game, but also not liking it, like eating a hearty meal that gets you sick. And, now, having played the game again, I remember.

Rialto’s a decent game, but it has two glaring weaknesses that combine to form a much greater one. Firstly, as I stated earlier, turn order in Rialto is very important. Going first in a given round ensures that you’ll have your pick of the best collection of cards. And, done right, it virtually guarantees you’ll be in first place on the Doge track for the remainder of the game. This is problematic. If the first person always grabs up the card row with the largest combination of Doge cards and Jokers in it, there’s no method for anyone else (aside from a couple of buildings) to even have a shot at surpassing them. Which brings me to my second gripe: luck of the draw.

How well you do in a game of Rialto largely depends on which cards you wind up with on any given turn. This all comes down to sheer, dumb luck. The only way to guarantee you’ll get the best grouping of a theoretical lot of lousy groupings is to be the person furthest along on the Doge track, which, as I already complained about, is a difficult position to wrench from another player’s grasp. Then, you’ve got the Jokers as well as a few buildings, but these are only useful to you if you actually have them in your hand or have actually gotten the opportunity to build them (and even then, you’re still going to need coins to activate them). Outside of those, there’s no built-in method for overcoming the luck of the draw.

Consider a game like Catan for an example of how this could have been implemented. Catan has a built in 4:1 resource trading ratio. If you’re stuck holding a hand full of grain, for instance, and need brick, you can use the built-in mechanic to ditch four grain to grab the brick you need. I really wish that something like this existed in Rialto because there’s nothing worse in any game than losing due to something that’s entirely out of your control.

Another smaller issue is the victory point track. In any game, the game board is the game’s main focal point. While a great deal of effort is often put into making it look appealing (which is important), there should also be an emphasis on functionality and clarity. In the case of Rialto, in terms of the victory point track, it has fallen short when it comes to clarity. Not only have they opted to go with dark colors that do not contrast very well with each other, but there’s also no clear delineation between the spaces. You might take a look at it and say “But David, the empty space between the lightposts is obviously where the score marker should go” and you would, theoretically, be correct. But, in practice, it just doesn’t work very well. It’s functional, but it’s a real pain in the neck to use.

One of the things I do like about Rialto, though, is the way that it turns the concept of turn order on its head. While going first in the round is highly desirable (for reasons already mentioned), going last in any given Phase is even more so. Playing through the different steps of Phase 2 isn’t as much about playing as many cards as you can as it is about playing only just as much as you need in order to earn that step’s bonus. As you can surmise, outbidding your opponent is always easier when you already know what they’ve bid.

This leads to some interesting situations where you’ll find yourself purposefully underbidding in a step that you could have won in order to guarantee that the person to your left will win because what you’re really after is the bonus from the following step and you want to ensure you’re bidding last when that comes around. And, if that sentence sounded complex, then I’ve done my job. Rialto’s a game where you’ll frequently find yourself jumping through logical hoops like this.

That’s why, despite my misgivings, I like it. Even though it’s got some flaws, Rialto’s still a pretty solid game. It tests my mental fortitude in unexpected ways. It forces me to pay attention and to think. And it’s fun. While it isn’t the greatest game that Stefan Feld has ever designed, it still ranks up there pretty highly. If you’ve never played it, you should definitely give it a try.

Add Comment