Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

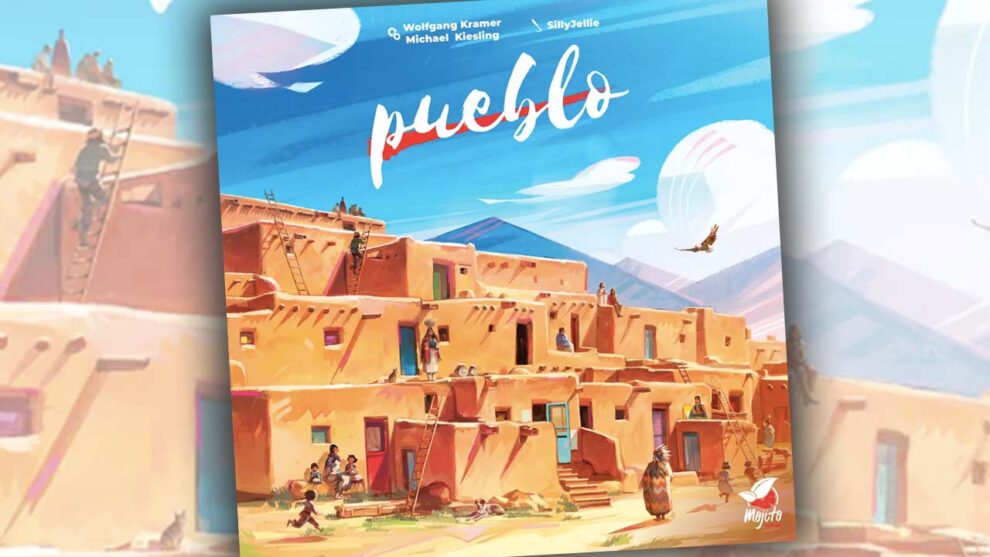

I wanted Pueblo to be an under-appreciated gem in the Kramer & Kiesling catalog. I wanted to tell you, “We are all so blessed to have a title like this back in print, and in such a beautiful edition.” My level of anticipation was reasonable. I didn’t expect it to be a masterpiece; I expected it to be interesting. I wasn’t hoping for a home run so much as a clutch bunt single.

Instead, Pueblo is perfectly okay.

Brick by Brick

The board is a grid, divided into four quadrants. Around the border of the grid, there’s a hawk token, which is used for scoring. On your turn, you place a block and then move the hawk.

There are limitations on both, of course. The blocks, which are unusually shaped, have to be entirely flush to any and all surfaces below them. You can’t leave any vertical gaps. The hawk must be moved, and can only be moved, between one and four spaces.

The hawk is important. It’s the only way points are scored. Each time the hawk is moved, the pieces it can see—i.e., the pieces with horizontal exposure in that direction—score points for their owners. A visible piece on the first floor scores 1 point, on the second floor scores 2, and so on. The corner spaces on the hawk track trigger an overhead scoring for that quadrant. If you look down on the board, each visible square scores 1 point. Once the game is over, and all players have played all their pieces, the hawk does a full lap, scoring every position once more.

The catch to all this? The goal of Pueblo is to score the fewest points.

A House Is Not a Home

Pueblo is a game of mediation. You will score points. It’s a question of how few you can manage. Half the pieces you place are neutral, used as sight blocks, but all the pieces are shaped in such a way that you end up with exposure. The board forces everyone to build together in time, there’s only so much space, but it’s also in your opponents’ interest to intermingle with you. As far as sight blocks go, your pieces are better than neutral.

What I wanted was for more interesting decision making. At a certain point, the game basically plays itself. As the board develops, you only have so many possible positions that aren’t outright suicidal, so you look for those and take them. It’s a problem of knowns; Pueblo is never opaque or mysterious. It’s all right there for you to see, from the beginning.

There’s an included bidding variant, dubbed the Pro rules, where players bid points for playing position. That makes the game more interesting, but it doesn’t impact the play experience itself, which never rises about the vaguely absorbing. Plus, there’s all that math at the end. I have often commented, “Ah, now it’s time for the best part: the score sheet” at the end of a game of Five Tribes, so I’m no stranger to the joys of addition, but the full circle of the board at the end of Pueblo is a bit much.

As my friend said, “I’m glad to have played it. Not sure I’d play it again.” Pueblo suggests some interesting design ideas. I was hoping it would embody them a bit more.

Add Comment