Board game reviews are a snapshot trapped in a very specific moment in time. Following somewhere between one and a dozen plays, enmeshed by current and recent experiences, a reviewer sits down to the keyboard (does anyone use pencil and paper anymore?) to pop off a few thoughts—thoughts which have hopefully moved from room temperature, through the boil, and on to a calm simmer.

Were any of us to revisit our thoughts on a title much later (as some occasionally do here at Meeple Mountain), we would do so under the influence of additional titles and in the faint glow of fresher experiences. We might discover modified tastes and cooled enthusiasm. Then again, we might also find rekindled delight or newfound appreciation that only time—or time away—and repetition can provide.

Sometimes we choose to review a title knowing our views are not fully formed or informed, but knowing also that we’ve reached a point of familiarity at which we can help others to see inside to make their own decisions. This, friends, is where I find myself with Petrichor. If I were so bold, I might call this Part One of a review whose sequel may arrive much, much later. I assure you, a very different Bob will deliver Part Two, but it will be worth the wait.

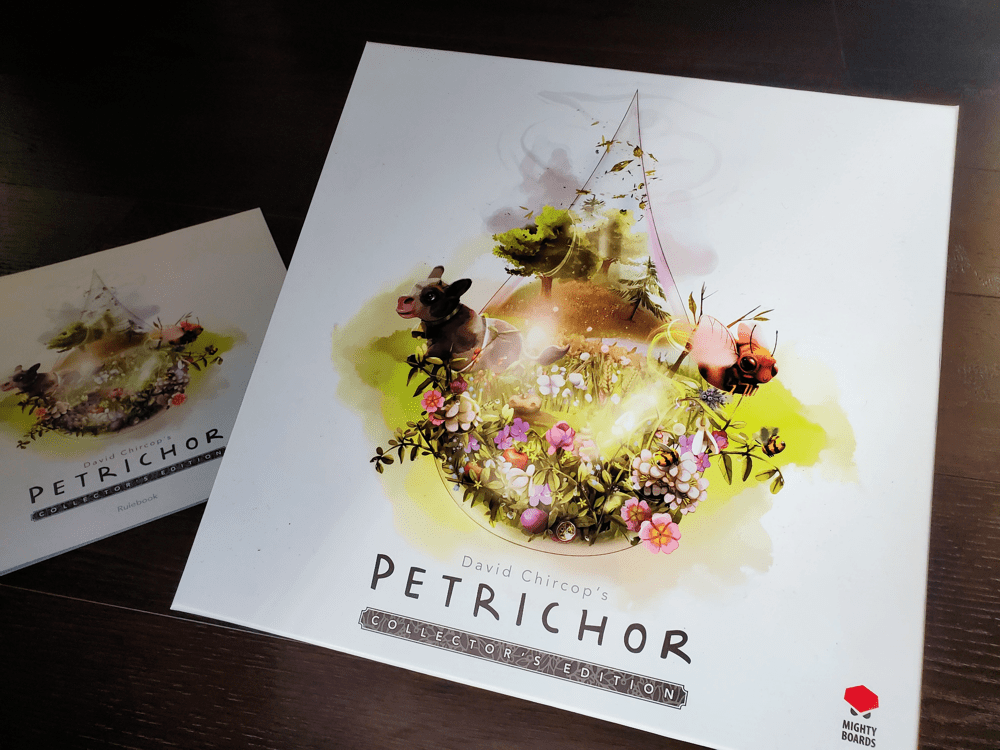

Petrichor is an area majority game from David Chircop (The Pursuit of Happiness, Hamlet) and Mighty Boards in which players control clouds and influence the weather via card play to introduce and effectively distribute rain over a field of vegetation. The name refers to the distinct smell that follows an often much-needed rain✝ / ✝✝. The box is stunning with its use of white space (I’m not shy about my love of white space). On the table, the components follow suit as they whisper, play me—especially if you’ve managed to take hold of the Collector’s Edition.

Under the surface, though, there is a mean streak and a strategic depth that lead me to believe I’ve not seen the half of what Petrichor has to offer, even without cracking the shrink on most of the expansion cards yet! But perhaps I’m getting ahead of myself.

Cumulus

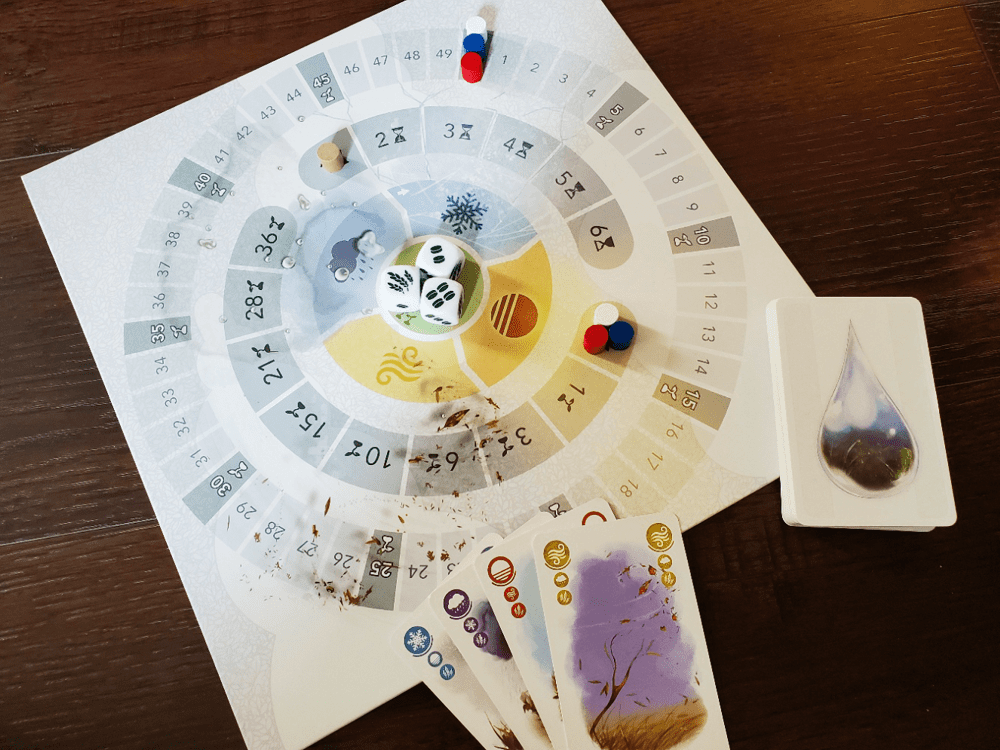

The two loci of play in Petrichor are the square Board, used to track scoring and shifting atmospheric conditions, and the Field of vegetation tiles. Area majority battles take place both above the Field inside the transient clouds and on the ground as rain falls, as well as on the influence track tied to Weather effects.

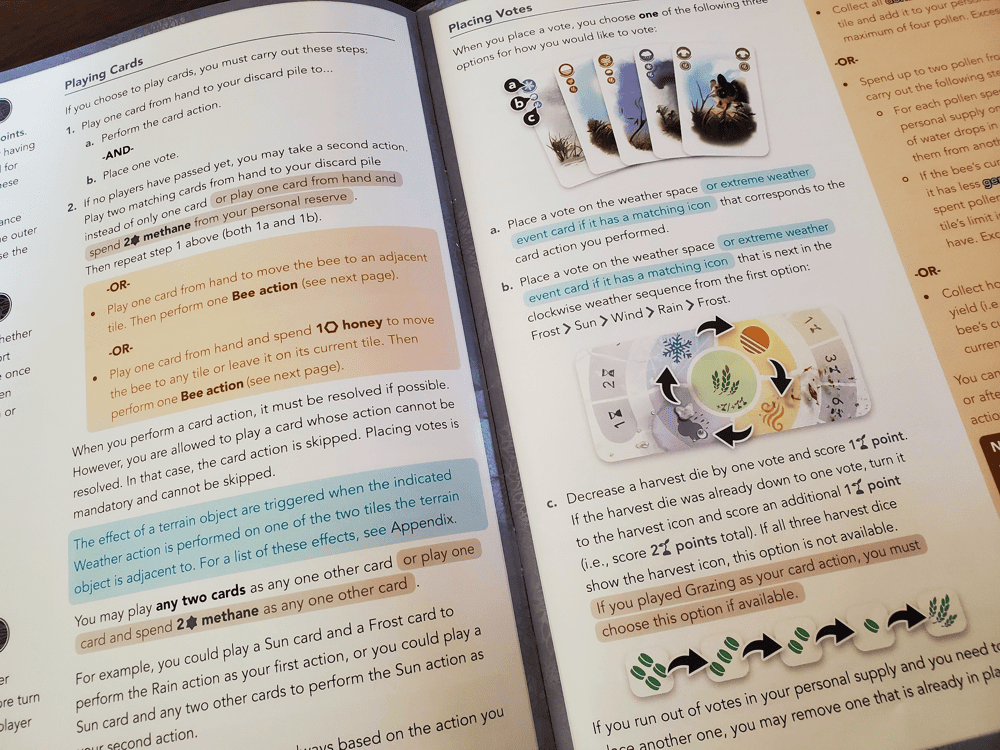

There are but many copies of only four cards in Petrichor, each one a mirror of one of the game’s Weather effects. On a turn, players lay one card, taking its action before visiting the game board to either influence upcoming weather conditions or move the game toward harvest by adjusting tracker dice and taking a victory point.

With a Frost card, players add a new light cloud to the Field with one of their own droplets inside. With a Sun card, players add two droplets to a cloud in which they already have a presence. With a Wind card, players move one cloud in which they are present one orthogonally adjacent space. Should two clouds collide, the droplets are combined and a lightning token is added to indicate the creation of a thundercloud. With a Rain card, players may rain one of their droplets from up to two clouds to the Field tiles below. At any time, two cards may be played as a wild should one be needed.

If at any time a cloud holds four droplets or more, it becomes a thundercloud. If a cloud reaches eight droplets, it releases its rain to the tile below. Empty clouds are always then removed from the Field.

Adding a touch of complication, players may also take a second action, but at the cost of two matching cards instead of one. So, having taken a Frost action to add a cloud, they may then take an immediate Sun action to bolster the cloud by playing two Sun cards right away. There are times where this sacrificial course of action makes sense to squeeze in a needed advantage. The only occasion on which this is not allowed is after any player has passed.

After playing a card, players choose to either add an influence token to the upcoming Weather effects or advance the Harvest dice, claiming a single victory point. Keeping life interesting, influence tokens must be placed either to match the card played or on the next clockwise effect on the board. Should all the Harvest dice reach zero (indicated by a Wheat icon), there will be a Harvest of points from the Field in the current round.

When one player decides to pass, they must discard their remaining cards (except in two-player, but for now let’s not worry about that) and claim the first-player marker. Each other player takes one additional turn and the game moves to the Weather phase. In addition to acting first in the next round, the first-player marker also grants a player the right to resolve ties in the forthcoming Weather phase—at times, a most critical privilege.

Stratus

In the Weather phase, players evaluate the four Weather effects to see which have received the most influence. Only the top two will occur, with the player whose tokens are most abundant moving up a separate scoring track. Frost turns every cloud into a thundercloud. Sun allows each player to double their presence in one cloud. Wind enables each player to shift any one droplet from a Field tile to an orthogonally adjacent tile. Rain unloads every thundercloud to the Field below.

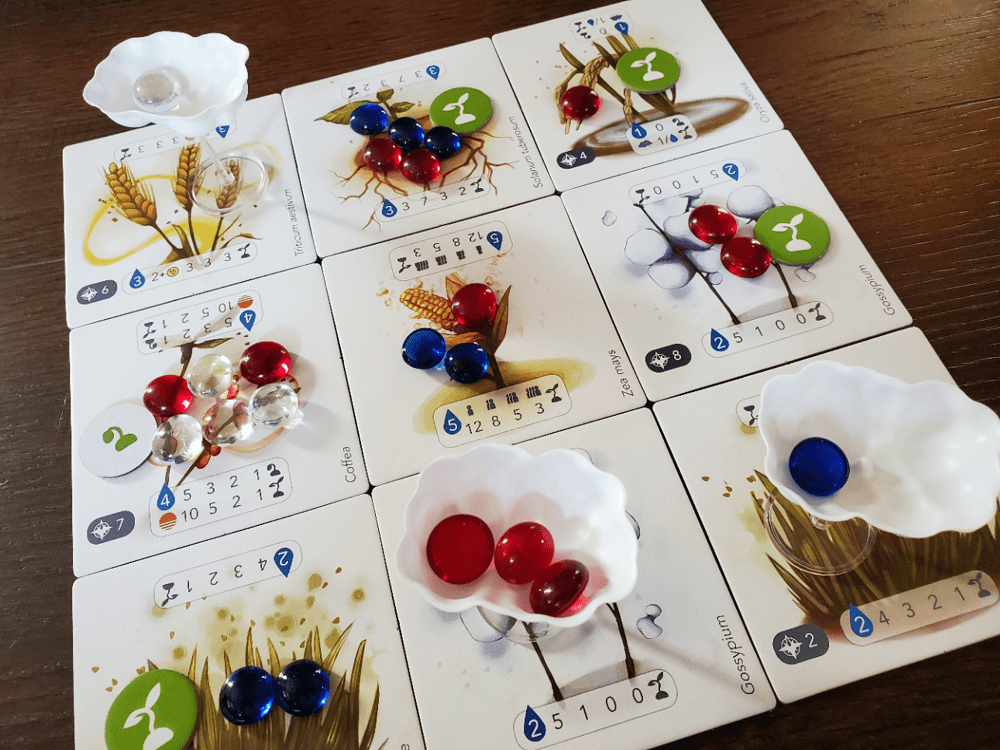

Following the Weather, if the Harvest dice all reached their zero hour, there is a Harvest. Each crop is evaluated based on its scoring condition. Every crop requires a specific minimum number of droplets to score. Some, such as grass and cotton, then require only a simple majority. Some, like potatoes, reward more to the second most droplets. Others, like coffee, offer more points if certain Weather effects were in play that round. Others yet reward based on the number of different players represented in the Field. Generally speaking, all scoring droplets are then removed from the Field and a new round begins after some board maintenance and a new hand of cards.

The game ends after either four or six rounds, depending on the desired experience. Four rounds tend to be more tactical as the decision space is tighter. Six rounds allow for a few longer term strategic decisions. Players receive bonuses for the number of times they dominated the Weather effects, plus any points for bonus tokens awarded by certain crops.

Stratocumulus

I’ve left out a bevy of minutiae, but there are several points to include:

The two-player affair is largely the same, but passing no longer comes with its penalty or its reward. No one discards their hand, but the first-player marker also stays put. The marker’s home is determined after the Weather phase, going to the player with the most influence tokens still remaining on the Weather effects board. This greatly alters passing in the duel and gives an unusual weight to the placement of the influence tokens.

There is a drafting variant in the back of the rulebook that I would consider a necessity. Random card deals can heavily skew the game in one player’s favor without the special abilities that come with the Flowers expansion. A draft affords each player some agency in determining their desired and available actions in the coming round. We never play without.

Finally, I appreciate that Petrichor is a game of finite resources. When droplets run out, players must retrieve droplets from the Field to place back up into clouds. As I see it, that’s all the right kind of dirty. Likewise for influence tokens on the Weather effects board.

Nimbostratus

I didn’t realize until I started writing just how difficult it is to describe Petrichor without images. To this point, the game may sound rather pleasant, even if a wee complicated. Puffy clouds traveling about, releasing their stony droplets to the beautifully illustrated crops below. How nice.

Make no mistake, Petrichor is a hawkish endeavor. These clouds, they don’t always play nice.

If you need evidence, look no further than the Wind. In the air, playing a Wind card often means invasion. Your neighbor has peacefully built a manageable majority presence above the wheat, which might mean two points and a wheat token should the cloud rain down. But the majority stakeholder of wheat tokens receives a dozen point bonus at the end of the game. We can’t have that. So we casually blow in, adding our droplets to the mix, creating a thundercloud. Maybe we take the opportunity to double up, playing a sun to gain the majority and drive the cloud over eight droplets, forcing the water to the ground before the neighbor can respond. Regaining the majority means another cloud, and there just might not be time before Harvest.

But that’s not all. On the ground, Wind means moving droplets. I said it beofre, I’ll say it again: that means any droplet. It need not be your own. The Wind brings change, and sometimes pain. Now, obviously everyone could simply move their own droplets to their own advantage, jumping in on a tile that will Harvest. But sometimes moving just one opponent’s droplet can erase the conditions necessary for Harvest or shift the balance of power.

In our most recent two-player affair, my wife and I spent an entire round zigging and zagging a single cloud across the Field. I was trying to drag it over the potato because I was the minority holder. She was trying to pull it across the wheat, which would have been good, to the coffee, which would have been even better. Eventually, she unleashed a second action and rained us down to her favor. On one level, Petrichor is always pretty. But on another level, it ain’t always pretty.

Likewise, the majority battles over the Weather effects have a pressure all their own. Sure, they are simply called “votes,” but getting ahead on the scoring tracker tied to these tugs of war can make a massive difference in the endgame. Plus, as several crops are triggered by specific Weather conditions, the skies over this side board can be a bit ominous as well.

I suppose it’s all in the attitude around the table.

Altocumulus

Though I can say with certainty that I don’t fully understand what’s possible in Petrichor, I can also say with certainty that I’m loving it.

Opening the game is a feast for the eyes—keep in mind mine is the Collector’s Edition, complete with the Flowers, Honeybees, and Cows expansions as well as every promo the game has to offer. The GameTrayz inserts are magnificent. The boards are high quality. The clouds are so deceptively cute. The cards are sturdy. The tiles are sturdy. The white space gives everything a clean appearance. The artwork is stunning. Mighty Boards knocked the production out of the park on this one.

The Collector’s Edition rulebook is also quite amazing. The various expansions are color-coded, meaning the rules read straight through and you simply read the color portions you’re employing along the way. There are ample pictures and examples throughout, plus a helpful glossary for the occasionally dense iconography in the back. The base icons are straightforward—only the expansions and extras need that extra bit of clarification.

The sixteen base game crops mean every session will be different. Even at four players, only twelve are required, meaning countless permutations and combinations abound. We’ve had great potato battles at multiple player counts, great wheat skirmishes as well. Corn is always a matter of intrigue. How cool is a game where you can say that?! I love that each crop has its own personality. Each is also labeled only according to its Latin name, a rather brilliant means to highbrow language independence.

I have utilized the Flowers expansion, the simplest of the bunch. Player power cards provide an additional offset to the limitations of the cards. Forecast cards grant potent single-use abilities to create and capitalize on opportune situations. Three additional crops—the dandelion, the primrose, and the snowdrop—each come with relatively straightforward scoring conditions. As an expansion, this one is pretty seamless and helpful. As for the Honeybees and the Cows, I’d imagine future Bob will have to return to discuss these along with additional insight gained from many more plays.

I believe the barrier to entry for Petrichor is higher than it might appear from its wispy toy clouds and zen-like stones. Every decision intersects area majority considerations in the sky, on the ground, and on the influence board. While every decision makes an immediate splash, the ripples are sometimes more significant. Causing clouds to collide decreases the number of clouds available and the number of clouds in which a player is present. This is no small matter in the course of the game, especially with only four rounds. Choosing when to anger your opponent is likewise no slight consideration, as there are always opportunities for revenge.

Know that Petrichor could be a downright vindictive experience, and I’ve seen complaints to that effect. My wife and I tend to choose positive effects over the more spiteful. We’ll more often claim benefits for ourselves rather than heap detriments upon our opponents. That’s just how we play. You may look to the skies through more ruddy lenses. I can totally appreciate that. Though you’ll not find such a component in the box, I think everyone should know there are knives in the game should anyone choose to wield them. I don’t think every Windy decision constitutes brutality, but how your group wrestles with the tension might determine your enjoyment of the clouds.

I’m nowhere near ready to print a Petrichor strategy guide. Whether I win or lose, I often finish the game realizing just how much I’ve yet to fully understand. There are moments in every outing where I celebrate the way someone (usually someone other than me) is able to manipulate the skies and tilt the Field in their favor, or issue forth some combo of movement and rain, followed by Windy weather adjustments that completely flips the script on the way to victory. I love when a game has such depth of possibility, even if my own exploration falls short.

In many ways, Petrichor reminds me of Obsession in that the expansions, while exciting, should stay in the box until the base is thoroughly explored. I am thrilled to have them, especially the single promo crop tiles that can visit for a game without drastically changing the core experience. But I’ve yet to feel the tug of honey and methane that will undoubtedly alter the experience and my opinion forever.

For now, I say give Petrichor a try or two. I fully believe you’ll know after the first play if you see possibilities overhead. If you do, stick with it. It only gets more intriguing. Keep an eye to the sky over Meeple Mountain as well, because I’m sure I’ll have more to say with the changing winds of the future.

✝ Etymologically speaking, petrichor is a compound of Greek origins: petri-, meaning “rock,” and ichor, which is the venous fluid of the gods. Given the historically divine attribution of rain to the gods, it makes sense that the sweet essence released when precipitation strikes dry ground would receive such a name.

✝✝ Current research, reported in The Scientist, (vol 36, issue 3, 2022) is investigating the possible link of geosmin, a terpene common to the Streptomyces bacteria, and petrichor. The fascinating question is whether geosmin triggers the release of the sweet smell as an aposomatic signal, a chemical deterrent alerting possible predators of the presence of toxins. Even more fascinating is that the very same signal seems to attract friendly insects, such as springtails, which are often responsible for ingesting and spreading the bacteria to new environments via waste pellets. Don’t you just love when your hobby shows up in a periodical on your coffee table? And you thought it was just a board game about clouds.

Add Comment