If the tabletop hobby has improved my character in any way, it might just be the relative peace I’ve acquired regarding delayed gratification.

I remember the simpler days when I had no idea that publishers X, Y, and Z intended to release new titles from my favorite designers “soon.” I remember having no favorite designers at all, and therefore no reason to pay attention. I remember the days before I crowdfunded a game project, before I sat at the front window like a sad puppy waiting for that Kickstarter to show up.

In our team piece anticipating the releases of Essen SPIEL 2021, I was excited to tout the then-forthcoming Pessoa from Portuguese publisher Pythagoras. Early in 2022, I watched with glee as the first few reviews surfaced. But this particular title was more than a little unavailable on American soil. So, I waited—almost another year.

I’ve learned to appreciate waiting two years to get a game to the table. I can honestly say it doesn’t bother me all that much. I’m also learning to temper my expectations for said games. But for this one title, I decided to forego such stoicism in favor of downright giddiness.

Now that the game is mine, all mine, I’m not disappointed with that decision—not in the least.

Pessoa, by Orlando Sá (Porto, Rossio), invites players to explore the final 22 years of the life of Portuguese poet extraordinaire Fernando Pessoa. Over the course of his years, Pessoa developed 75 or more heteronyms, personas he would assume in the crafting of his poetry. More than mere pseudonyms, Pessoa would become these authors as he wandered Lisbon and wrote the verse for which he is famous. In Pessoa, players assume the role of these heteronyms, bumping around inside the head of their host, competing to inspire his final works.

If the thematic premise isn’t enough of a head-scratcher for you, what if I told you that there are only five locations on the board for four heteronyms and one Fernando to share?

So Alberto Caeiro was Pessoa’s mentor?

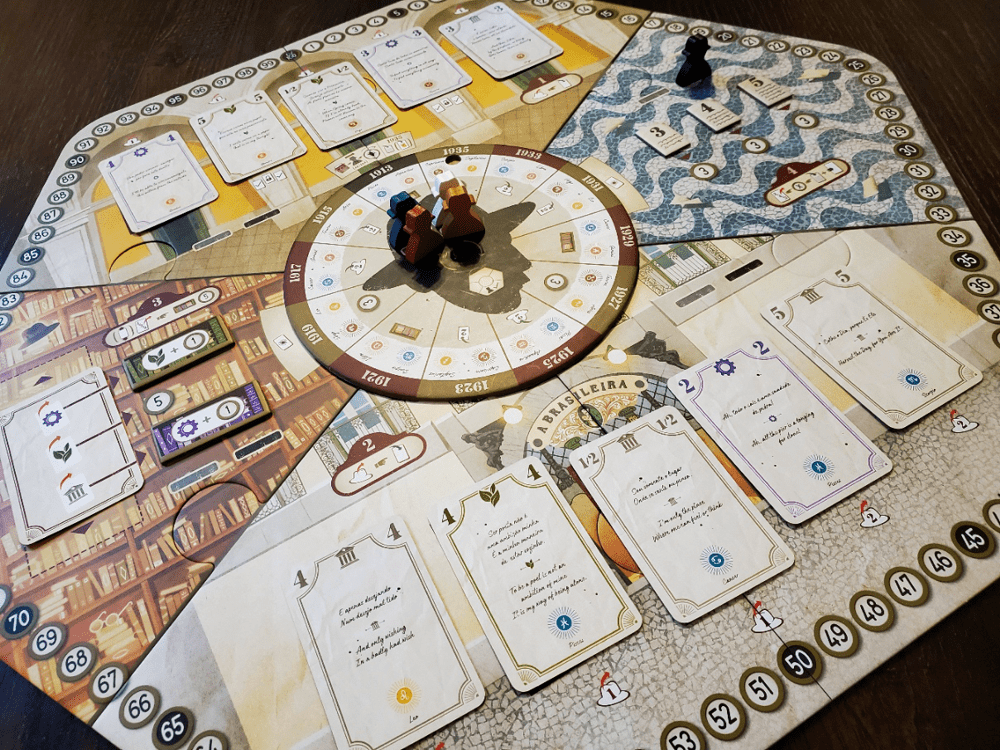

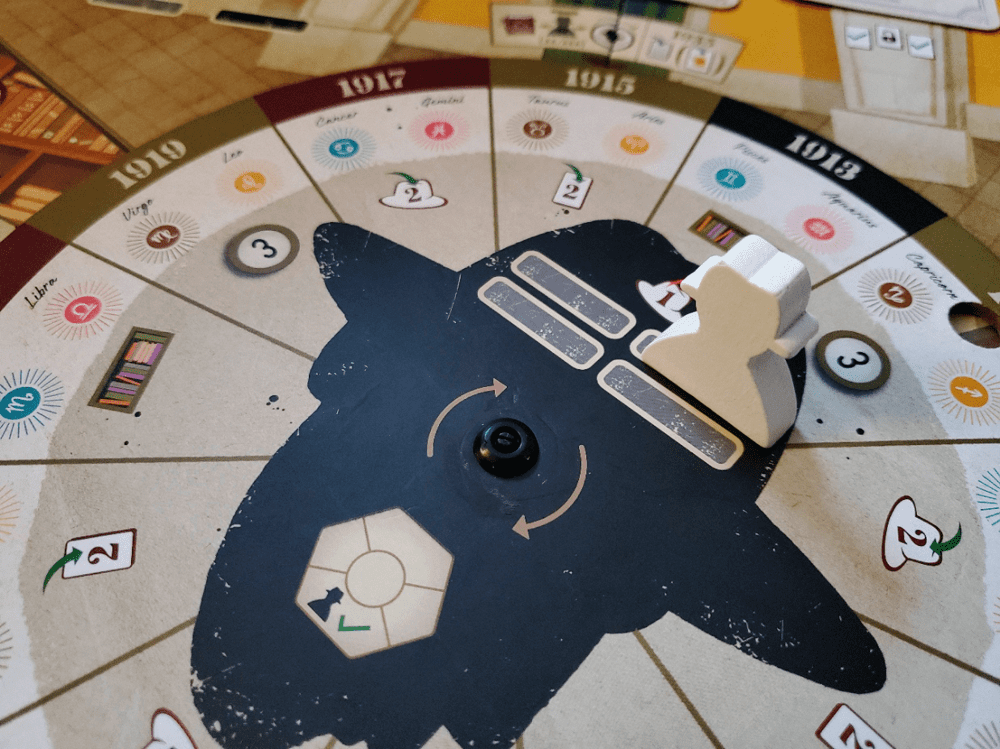

Pessoa takes place on a sizable hexagonal board of assembled puzzle pieces depicting four physical locations: two Cafés, a Bookshop, and Lisbon’s famous Rossio Square. The central location, Pessoa’s mind, is a large central dial that represents the metaphysical realm and spins to mark the passing of years. Each of the physical locations has a space for Pessoa himself and one additional space available for the heteronym fortunate enough to be out and about with him for the day. The central location has four spaces available only to the heteronyms, because it would be absurd for a man to enter his own mind.

In short, one player can share a space with Pessoa in the physical realm at a time. All four can share the space in his mind and, in doing so, do what Pessoa himself is doing.

Throughout the game, players control either their own heteronym via their meeple or Pessoa himself via the black meeple. Taking control of Pessoa costs one Creative Energy (the game’s currency) but the benefit is unrestricted movement around the board since there is always an open space for him. Because every turn requires a move, however, players may also elect to enter Pessoa’s mind via their heteronym meeple where they can take his action without moving him. This, however, does not grant any lasting control of the poet’s physical form. Confusing? Perhaps at first, but the situation makes perfect thematic sense if you think about it.

Players will take only twelve total actions as the dial turns and the years pass by. Choosing whether to operate via Pessoa himself or his heteronym makes all the difference in accomplishing a task.

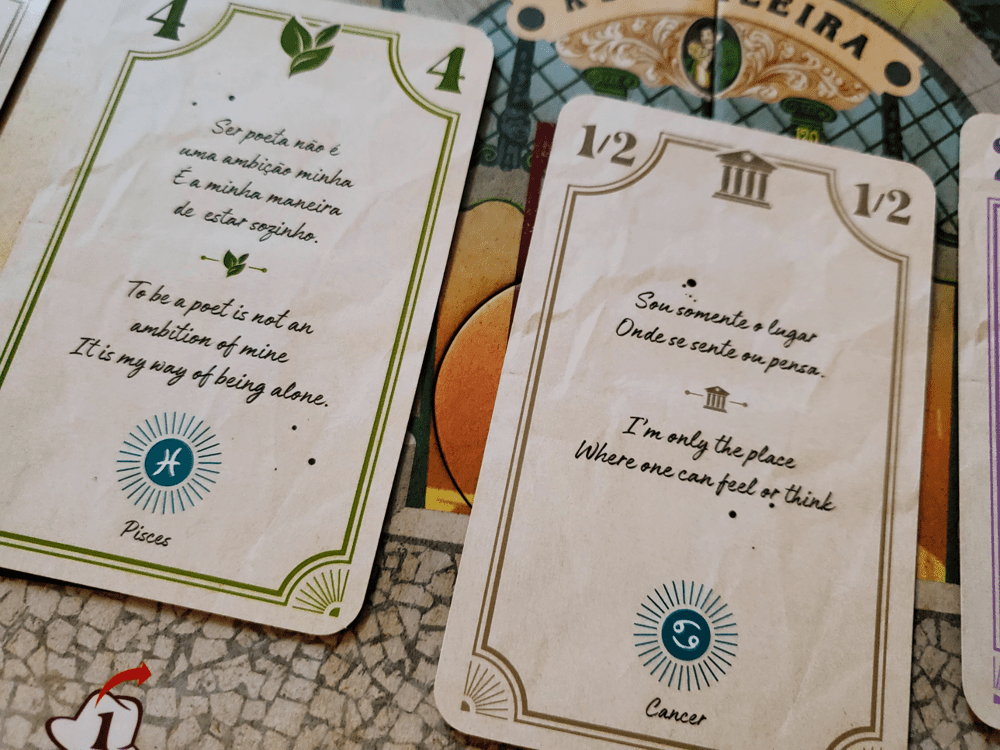

On a given turn, players could visit one of the two Cafés to spend Creative Energy to gather cards bearing poetic lines. Cards come in one of three suits with lines printed in both Portuguese and English.

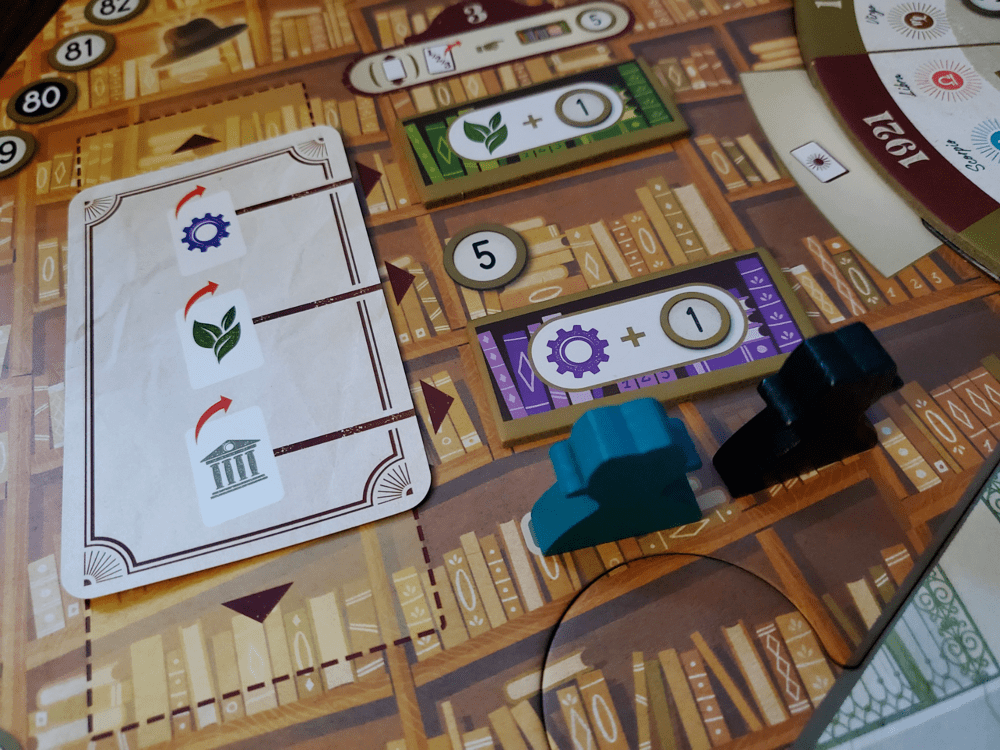

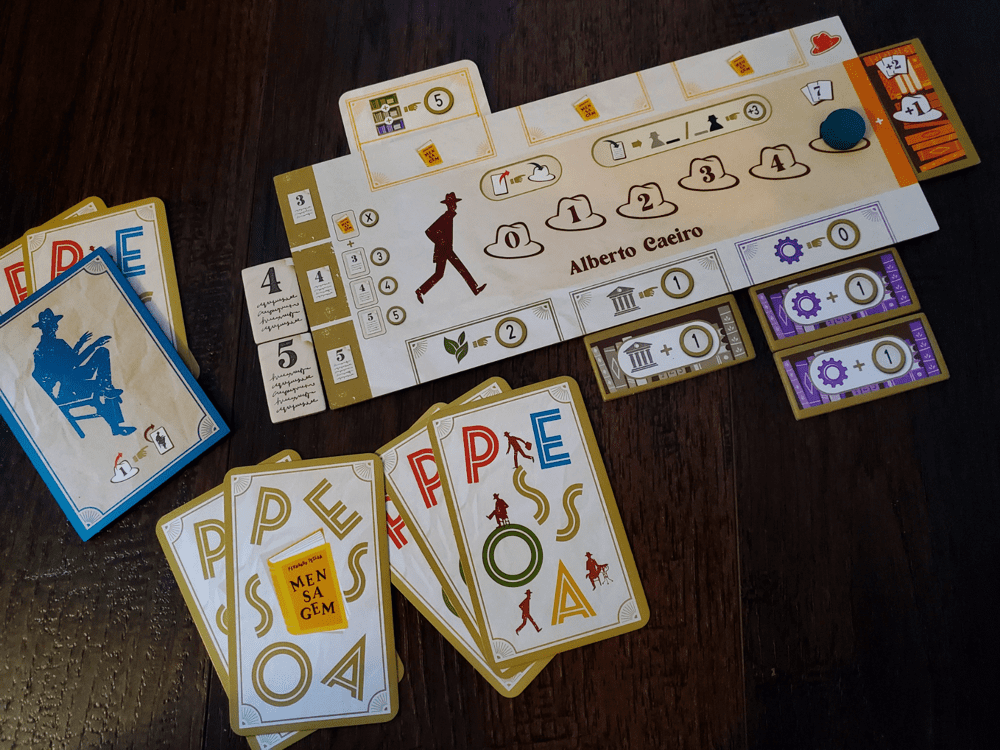

Players might visit the Bookshop instead to spend cards to upgrade their player board, which tracks Creative Energy and various scoring mechanisms. The players’ heteronym boards have two sides, one with a universal setup and one with an asymmetrical setup. The Bookshelf tokens can be used to adjust scoring for a particular card suit or increase the capacity for Energy and cards.

The Bookshop “pricing” is fluid. The card that lists the prices can slide in one direction or another to adjust which price is associated with which item. It is a beautiful idea to allow for flexibility in a very, very tight economy. After laying out cards in exchange for upgrades—no doubt the poet read them a line or two as payment (poetry isn’t always a lucrative gig, you know)—a new pricing card replaces the old.

Rossio Square, the fourth physical location, was one of Fernando’s favorite spots. In the game, it is the place for finalizing a poem. Three, four, or five cards in ascending—but not necessarily consecutive—order comprise an oft-confusing work of creative genius. Each poem scores immediately based on: number of cards, matching suits, and any other asymmetric conditions that arise from the player board. The first revealed poem of each length also earns a bonus. Of course, the most important part is the accompanying dramatic reading followed by respectable table thumps and snaps.

Adding a layer of personality and forethought to the situation, Pessoa’s mind is dotted with astrological symbols. He was a fanatic in life. Each card also bears a symbol. As the dial rotates, two symbols are prominent in any given round. When cards played in Rossio Square and the Bookshop align with the stars, a bonus of cards, points, tiles, or Creative Energy awaits.

I said the economy is tight. That’s because each player has either five or six Creative Energy points to start the game, a paltry quantity that disappears almost instantly in either Café. In order to regain the Energy, players can discard those oh-so-precious cards or take a Rest action. Resting hurts in a game that only features a dozen actions, but it provides a refreshed stock of Creative Energy.

When 1935 comes and goes, the game ends. Players each offer one final poem consisting of a single card from their hand and single cards reserved from poems played throughout the game. After scoring this dying work, players receive one final boost from each previously scored poem and one heteronym rides off into the sunset with Fernando as his favorite persona.

But Alberto Caeiro is one of the heteronyms?

There are two modules that are obviously intended as essential. First is the asymmetry of the heteronym boards. On the green learning side, every card suit holds an equal value and every poem is worth its length in cards. Hand sizes are the same. Creative Energy is the same. This side is designed to ease into the tightness of the game’s economy and mechanics.

On the red experienced side, in addition to a singular asymmetric scoring bonus, every heteronym scores the suits differently and every poem’s endgame value is unique. Hand sizes vary. Creative Energy varies. In short, the backside sets the heteronyms free to be themselves, making life quite interesting. Because every heteronym in Pessoa’s life had a distinct personality and style, I believe this is the true Pessoa.

The second module is titled Mensagem, which was the title of Fernando Pessoa’s only book. These endgame objective cards add a beautiful tension. During a Rest action, the active player draws a third card to accompany their two and plays one into sight of all. Then every player passes one Mensagem card left. This revolving draft of objectives is, at times, agonizing. Because they are visible, everyone knows what would help their neighbor, and who wants to share? This interior bartering is also bizarrely thematic.

Wait, Fernando Pessoa was one of Pessoa’s heteronyms, too?

Let me make two things clear. First, my inaugural play of Pessoa was exceptionally awkward. Second, I loved it anyway and have loved it more with every play.

That first play is awkward because of just how suffocating the placement mechanism can feel. No matter the player count, all four heteronym meeples are employed on the board (an artificial rotation scheme shuffles them during solo, two, and three-player games, but it’s most enjoyable with four humans). It is entirely common to be unable to move or to have only one open space. To some, this might feel like there are no decisions to be made—simply take what’s available.

It might also feel like the only way to get things done is to control Pessoa, leading to a perpetual expenditure of Creative Energy. Did I mention you start with only five, which must also be spent to get the cards necessary to make poems? And that cards are also the means for purchasing upgrades? Of course, then you remember that taking control of Pessoa still requires movement, but you didn’t want to move, so you have to go to the metaphysical mind space instead. Wait, how many actions are there again?

Folks, there is delicious tension in these decisions. Not because they are not, at times, obvious, but because they are quite obvious and decidedly painful.

Astrology provides the only significant relief to the tension, but it requires a keenly attentive player. On the one hand, there are two symbols available in every round, so the odds are you’ll achieve at least some of the benefits of a match. I can also tell you winning requires achieving those benefits nearly without fail, which will not happen by chance. If you want to feel like you live and die by your horoscope, play Pessoa, because, in essence, you do. Every purchase of cards involves a peek to the dial and what’s coming next. Every poetic composition, every visit to the Bookshop, is timed to align with the stars.

There are only twelve actions, but every one must be planned because every ounce of Creative Energy is precious; every card must match; even Rest must be precisely enjoyed.

On the matter of Rest, the Mensagem cards are fantastic. They are quite simple: perhaps a few points for having the most green (Naturalism) upgrades or the most poems of 4 cards. There are no mind-blowing quantities involved, but every point matters. Passing those points, repeatedly, around the table is stressful because you know you need to keep one card and you know the other card will help either of the next two players in line. Is there time for spite in this obsessive mess?

Because every line of poetry is wrenched from its context, reading the poems is an exercise in silliness. I know as I keep playing I might grow weary of reading them. Of course, I could always just read them via a heteronym voice for dramatic flair. Or maybe I’ll grow in appreciation for the oddity of it all, especially when I pull together a verse or two that seem to belong together. We’ve had moments of raucous laughter with the surreal combinations. I wouldn’t complain about a supplemental deck that injects new lines down the road, but the sixty in the game will suffice for quite awhile.

I would hardly call Pessoa a game for everyone. It is highly thematic, so if you’re not looking to rummage through an eccentric poet’s head, you might not be thrilled. It’s a worker placement game, but one where the meeples feel like they’re shackled. Some might not enjoy that. Plus the economy has all the comfort of a velvet noose.

But Pessoa is everything I had hoped it would be. The physical and metaphysical settings are lovely. The tension is engaging. The mechanisms are precise. The poetry is fun. Best yet, my family enjoys it. My friends have enjoyed it. I may jump in on the solo mode at some point. If I do, I’ll update the review, but I’d imagine I’d see merit there as well. This one was worth the wait.

Add Comment