Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

The bear in the Toblerone logo. We’ve all seen the bear, right? (Not to mention the letters for its hometown of Berne hidden in the chocolate’s name) Or the arrow in the FedEx logo—I can’t look at a FedEx truck without first seeing the arrow. The Pittsburgh Zoo, a frequent stop over the past forty years (maybe not as much for you as for me?), has employed similar effect in “hiding” a gorilla, lioness, and several dolphins in the white space of its remarkable tree logo.

As far as artistic vehicles go, logos are a simple way of demonstrating the use of negative space. More than the mere employment of white space, negative space is the portion of a creation that exists by its non-existence. It is found in the paint that was left unbrushed or the stone that was cut away. In the case of branding materials, logos often employ negative space to maximize the impact of a mark that must, by nature, speak a large message from within the smallest of footprints. Hence, when you only have room for a mountain, you tuck a bear inside that mountain. Stealthy.

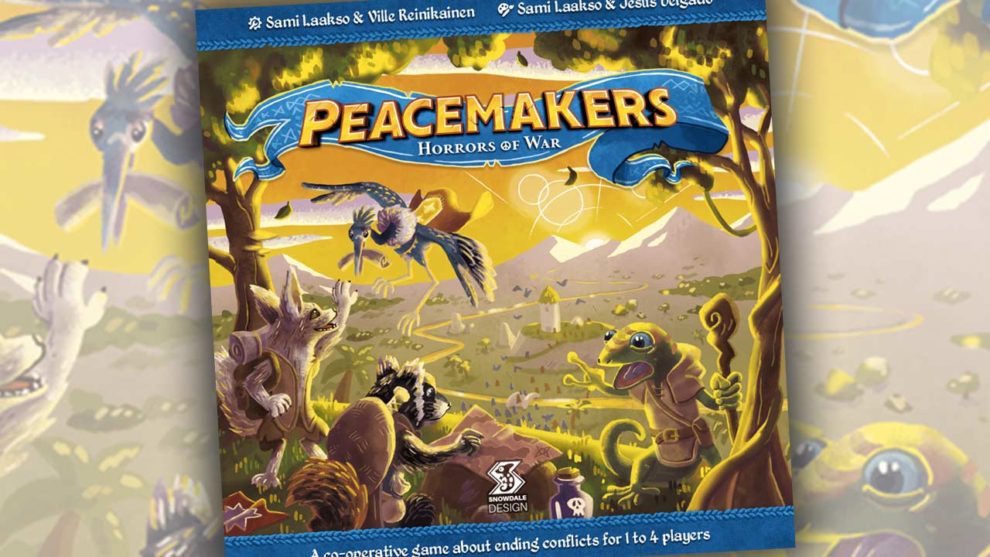

Recently I have been exploring a late prototype of Peacemakers: Horrors of War, a revamped scenario-based cooperative game from Sami Laasko and Snowdale design. Like its predecessor Dawn of Peacemakers (which I have not played), Peacemakers: Horrors of War is a game of battlefield negotiation in which players are attempting to bring two or more sides of a conflict to a peaceful resolution before any one side is brought to surrender. At its core, it is a solo game that can support the strategic conversation of multiple players, but the multi-player endeavor does have its merits.

Horrors of War, I would argue, is a game that takes place in the negative space of a skirmish game.

The paint

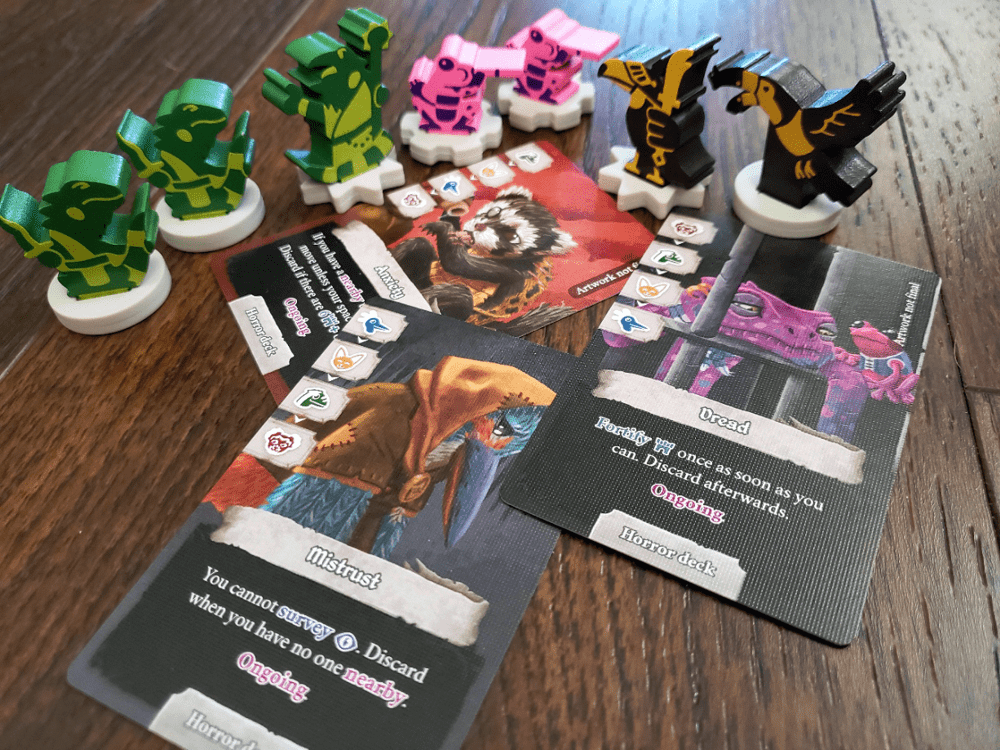

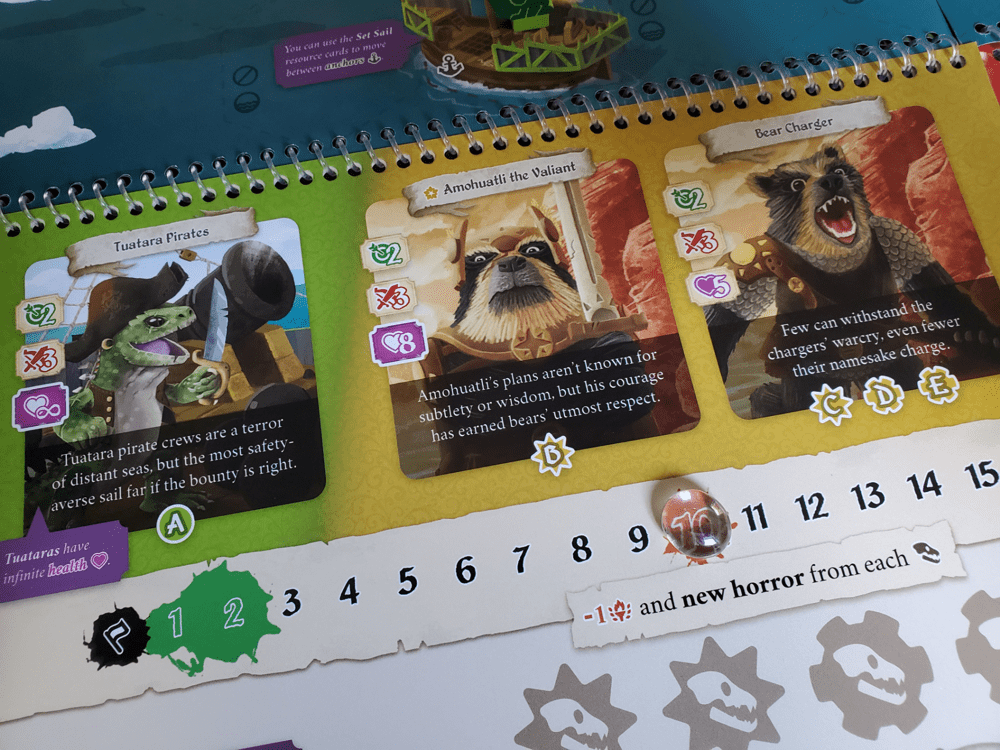

Two side-by-side map books (each one forming half the scene) create the battleground in Horrors of War. Animal factions, represented by beautiful, chunky, screen-printed meeples take their places on the map, each after receiving a rubber base that assigns a specific group according to its shape. The Adventurers—the players—set their meeples right in the middle. A bit of info on the various faction critters lies just beneath the hex grid.

The primary interest in Horrors of War is motivation. The factions want to fight. They advance upon one another, attacking as they are able. Your job as the peacemaker is to affect a decrease in both sides’ motivation. When the glass beads on the various motivation tracks dip into the green zone, they are ready to negotiate and the players win. Should either side’s tracker prematurely reach zero, though, there is surrender and the mission has failed.

In order to affect that change, players use their cards. There are four basic actions on the cards and one grander Scheme. The Survey action involves flipping one card from a nearby army’s order deck, revealing one piece of their forthcoming action. Following the player turns, the armies will act according to these order decks, so knowing their intentions is vital for thinking one step ahead.

The Travel action is for movement along the hex grid. Fortify involves placing fortification cubes to protect spaces on the map (not the critters themselves, though they are protected if their space is protected). The Delegate action—available on every card and therefore ubiquitous and unnecessary as an icon—means every card can be passed from player to player. Since some cards are more potent in the hands of specific Adventurers (a nice asymmetric touch), card exchanges allow for power plays when the right Adventurers are in play.

Each card also features a Scheme, a singular action designed to manipulate the armies by offering additional protection, singular wounds, a bit of healing, or by tinkering with the ordering deck. Such tinkering might include rearranging, discarding, or re-prioritizing the order cards before they come to fruition. Once players are out of options or satisfied with their cardplay, they stop and the armies take center stage.

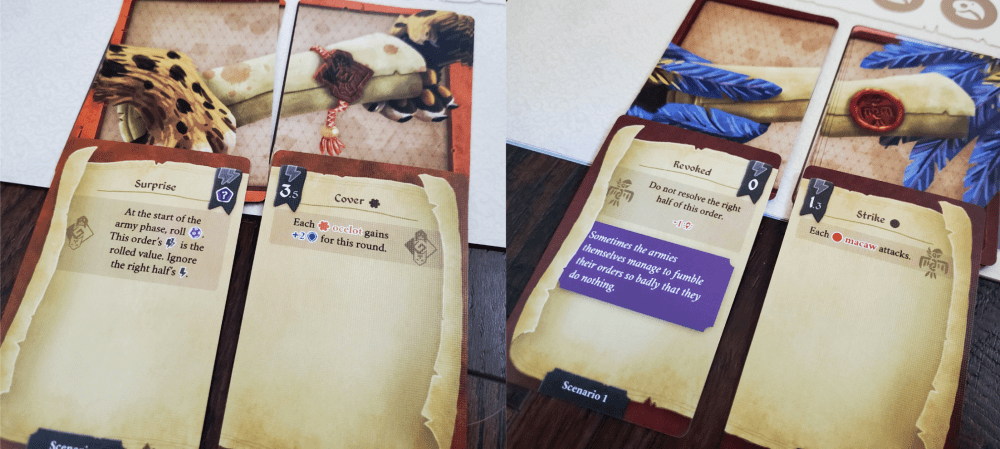

Each of the armies then reveals (if they’ve not been flipped via a Survey) and executes the top card in each of its order decks in order according to its listed speed values. Most of the cards work in pairs. The left card offers some sort of conditional effect tied to speed, dice rolls, or the action on the right; the right card instigates a bit of action. The action is often restricted to certain groupings (remember those rubber bases?) and might include moving forward, fortifying, attacking, or the like. There are stipulations in the rules for who attacks whom, who can move where, and how the various actions shake down. Damage is tracked by discs that follow the characters around the map.

If at any point a critter dies, a Horror card is added to the top of the Resource deck, which is the deck where player actions come from. These Horror cards will summon bad things to happen, sometimes as a one-off penalty, sometimes as a lingering effect. Either way, they are eventually added to the Resource discards so they may, at a future moment, return. Avoiding Horrors is, rather intuitively, a good idea. Each critter loss also means a decrease in motivation for the army, which sounds good, but is that really how you want to achieve peace? (Answer: Sometimes)

Following the army actions, players receive the top four cards of the Resource deck to start again (introducing Horrors if need be). Give or take some scenario-specific details,this is the pattern of the game until either one side surrenders or the Adventurers bring the parties to the negotiation table.

The effect

Even as a late prototype, Horrors of War is gorgeous. Every Snowdale production is charming to the nines. I love the move from the plastic minis of Dawn of Peacemakers to the sturdy wooden friends here. The rubber bases never fall off but slip on and off with ease. Everything in the box already boasts a finished quality. I imagine the crowdfunding campaign will offer upgrades, but I am left only with praise when it comes to the table presence of the pre-production copy. You won’t be disappointed in the way the game looks.

The box insert is wonderfully designed as well with adequate room for the full complement of missions. There are some great graphic design details included, like tabs printed inside the box bottom as labels for the scenario cards and faction banners printed outside the box in front of each of the cubbies for the meeples. I love when a game is neat.

(Standing in) the gap

Imagine, if you will, most of the tabletop games you play. You move around, you gather resources, you use those resources. Or perhaps you look at the board state and then play cards to make things happen. Horrors of War, in the strangest of ways, does neither of those things. It takes place in between those sorts of actions. As I said earlier, it lives in the negative space.

The armies are moving. The armies are attacking. As fighters, they have ranged attacks to execute, damage to issue, and health to track. Their war-torn turns involve checking spaces on the board to see if they grant additional boons like protection or stealth. Their order decks change the board state constantly, moving and slashing with each piece in its time.

But as players, you don’t do any of those things. Think about your actions. You can peek at what’s coming, but you’ll never have enough Survey actions to see everything. You can move around, which is important because you have to be standing with the critters you are trying to affect, but you can’t get to everyone. You can fortify a bit, but with only a few cubes (and who needs the help most anyway?). Often the Schemes allow you to alter the deck and the coming events, but you really need to see the deck to know what to change. That’s true for all of these actions, actually. And as I mentioned earlier, you only get four cards per round, regardless of the player count. Efficiency (or any semblance of what the heck you’re doing) comes at an agonizing premium.

Horrors of War is all about learning the character of the armies and the best ways to lower their motivations to achieve peace. For the first-time player, that will happen in one of two ways. First, you can go in cold, which I did in my first game, observing the deck and trying to figure out what the heck is going on in the battle around you. I cannot express how strongly I disliked that option. I felt lost—helpless. In that first game, it seemed the best way to achieve peace was to just let the armies die, but even that doesn’t work! I know that some love this sort of exploration, though, so that might be what calls to you.

The second way is to investigate the cards beforehand to learn something of the nature of the armies on the map. What sorts of conditions lower their motivation? Because two decks determine the orders most of the time, what variety of combinations could work in your favor? Without doubt or hesitation, I preferred this option. Mind you, the cards are still shuffled and there is no guarantee you’ll see the right combinations naturally, but I liked having a strategic thought or two as I began.

The first iteration of this game system, Dawn of Peacemakers, involved players creating each faction’s deck prior to play. They did so according to a chart in the rules, but the setup introduced at least a loose conception of the types of cards lying in wait. I say familiarize yourself in a similar fashion. Don’t think of it as spoiling, think of it as relationship-building.

I bring this up because Horrors of War is a game of patience. There are no shortcuts to victory. I was able to bring the two sides to peace in the first scenario, but not in that first try. I can’t imagine a real-life third-party negotiator coming to the table without any pre-existing knowledge of the parties involved. By the time you figure out what to do, someone will be unconscious or dead and the cause will be lost.

I will also add that Horrors of War is awkward. I can’t remember feeling so uncomfortable during a game. I wasn’t that far off in my understanding of the rules (I did speak with Sami about some of the nuances and my early mistakes during play), but that first exposure to the game felt so inert. I felt like I was watching the war happen, but I couldn’t make a difference. I surveyed the future, but in doing so, I felt like I was just skipping ahead to the part where I would lose. For a moment I thought that was the point and I was distraught, but I persisted.

I’ve now come to see the balance involved in trying to know something without knowing everything. And, of course, then using that slice of something to my greatest advantage in altering the conditions of the war. I admit, I still feel largely helpless when I play, but I do feel like I can make small strides toward a difference. There is room to learn and grow in the system.

The estimated duration of each play begins at 90 minutes. That’s a long time to tread water, especially if you’re playing alone. But that also means there’s a lot to experience in this delightfully illustrated box if you have the stomach for it.

For those interested in tossing a few bricks overhead while they tread, there are also challenges in the scenario book—layers of impossibility to add to the impossibility. Try pulling it off when the motivations are incredibly out of whack, or without a single death? Yikes! I am relieved that I was able to find a way out of the base scenario, but I don’t know if I can hang with the challenges when I was only making a dent in the follow-up.

If you can’t tell, I have engaged Horrors of War as a solo play. In a slight breach of the rules, I have tried playing with multiple Adventurers as well, though not with additional human players. I believe I would welcome the conversation in solving the puzzle of it all, but I’m not sure I would want more than one partner to actually play. The idea that most cards can be shared just means you’ll shuffle the cards around until the right Adventurer is carrying out the right action. In theory, you could pass the cards around the table until everyone sees them, then talk about the best way to use them. It just feels like you’d all be serving one collective solo mind anyway, so I say keep it open-faced and talk it through. The only question is how many asymmetric powers you’d like to have active for the task. If you’re looking for a bit of a power-up to solo play, though, I believe the system can easily bear the use of more than one Adventurer until you’re ready to try it alone.

No matter how you approach the battle, Horrors of War is a unique puzzle that turns a lot of typical tabletop expectations on their head. I’ve not seen anything like it. But is this puzzle for you? If you’re a resource collecting, resource spending, victory point tracking, efficiency-focused euro gamer, possibly not. If you aren’t particularly excited by the idea of hiking through mud, possibly not. But if you love digging into the psyche of a battered macaw chief to figure out what would make him lay down his arms (or wings) to make peace with a rival ocelot, without a traditional game resource in sight, Horrors of War might be calling your name. There will be seven factions to explore, six scenarios to unpack, and puddles of sweat left behind. I have no doubt there are depths to enjoy if you are intrigued by the challenge.

In the end, Horrors of War is not a game for me, but I am impressed with the (negative) space Sami has cultivated to scratch a very unorthodox itch for the peace-loving puzzle jockey.

Add Comment