I’m going to start this review by saying that Pax Pamir (2nd Edition) is a fully-realized and beautiful work of art, and if you can find a copy of it, do so. It’s absolutely worth playing and owning. If that’s as far as you read, I’ve done my job. Still here? Cool.

Now I’m going to talk about history in games and accessibility, because I think Pamir has an underlying argument about what games can be, and what historical education can be, and this argument is powerful.

History Lessons

Pax Pamir is set in the period of time that is often referred to as “The Great Game,” when Russia and Britain waged a hot and cold war in Afghanistan. The players in Pax Pamir are not any of these big nation-states, but instead you’re small power brokers and local leaders. History-wise, and writ very large, Britain wanted to protect the borders of its then-colony, India, and Russia was looking to expand its borders, or just generally make Britain uneasy.

For the cliff notes version, there were a lot of white men in parlors making ill-informed decisions about a region they didn’t understand, which resulted in a conflict that created ripples that still inform our present moment. The Afghans that the Europeans sought to influence had their own interests and motivations, and some of the stories of historical figures like Dost Mohammad Khan, Alexander Burnes, Shah Shuja, and Jan Witikiewicz wouldn’t be out of place in an HBO soap opera.

My reading of Pax Pamir is informed by one primary source, Edward Said’s Orientalism. To paint very broad strokes, Said’s argument was that colonial narratives (in particular British ones) say a lot more about the colonizer than the colonized. The way Britain thought about Afghanistan says a lot about Britain, and not much about Afghanistan. Why does this matter? The European powers meddling in Afghan affairs thought they were playing a game, a game that they thought they could win, a game that thought they knew. When you sit down to play Pax Pamir, you too will be playing a game – how you play it will say something about you.

Games and Models

“Most board games and video games that are about something are models. Trading games, railroad building games, shooting games, strategic war games. They all communicate the game designers’ model of certain aspects of human affairs.”

-Volko Ruhnke, Shut Up and Sit Down Interview

We’ll come back to Volko in a moment.

The Pax series is a bunch of games that share certain concepts loosely. Most of them involve building a tableau out of cards that are bought from a marketplace. The marketplace is full of historical figures, equipment, locations, and purchasing and playing these cards changes the game state. Each of the Pax games has its’ own arguments about history, and some of these are controversial (here’s looking at you Pax Renaissance and Pax Emancipation), but I won’t go too much into that here, because Pax Pamir is a different designer with a very different argument than those games. If you’re looking for an interesting breakdown of some of the other games in the series, I recommend this (somewhat) lengthy article.

Pamir is designed by Cole Wehrle, of Root and John Company fame. I’ll get to what I think his argument is in a moment, but here’s how Pamir works.

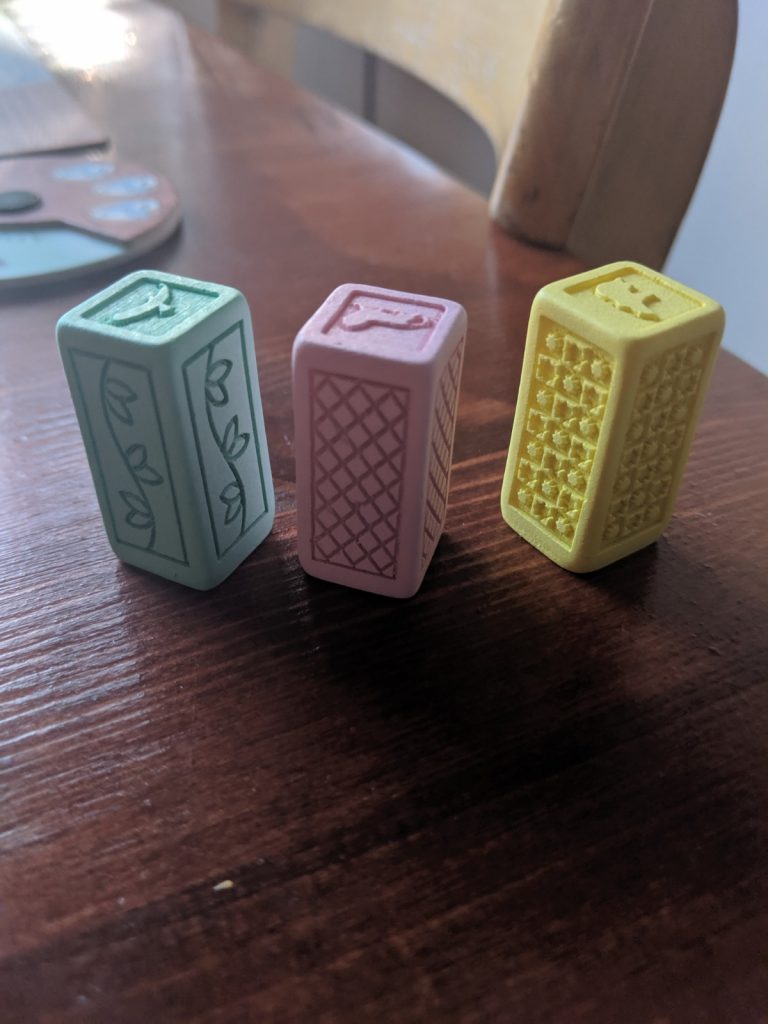

There’s a map of Afghanistan, and there’s a marketplace full of cards. Purchasing and playing cards brings resin blocks in one of three different colors/nationalities onto the board (British, Russian, Afghan nationals), as well as bringing on players’ own personal spies and tribes, which are represented by wooden cylinders.

The tableau that you build out of these cards will enable you to move the blocks around, move your spies and tribes around, fight battles, destroy other players’ cards, build roads, and gain income. Periodically, four “dominance cards” will appear in the marketplace. When a player purchases one of these cards, two of them enter the marketplace, or one gets discarded from the marketplace, a “dominance check” takes place. There are two different victory checks in the game. If one faction (British, Russian, or Afghan nationals) has four more resin blocks out on the board than anyone else, the player with the most influence with that faction gets five points, second place gets three, and third place gets one. If no faction is dominant, players compare how many of their own spies and tribes they have out on the board, first place gets three points, second place gets one point.

If at any point a player has four more points than any other, they win outright. Otherwise, after the fourth dominance check, the player with the most points wins.

A crucial point in the game is that each player is always in a coalition with one of the factions. This can change through a number of in-game actions, but when you’re in a coalition with a faction, you move its pieces and place them on the board as well. In this way, Pamir resembles an investment game. Multiple players can be in a coalition with the same faction(s), leading to impromptu alliances. It is a game where every player can be on the same side. In this way, the way the game progresses is dependent on the players.

So, let’s go back to Volko.

I think the fundamental model that Pamir is working through is one about power. People often call games like this “sandbox” games, which refers to a style of game where players direct the game within a given set of rules, rather than moving along a predetermined structure. Pamir has structure in spades of course, at least in how the game begins and ends, but the tenor, flavor, and movement is directed by players. Cole Wehrle could have picked any theme for this type of game, but he chose “The Great Game.” If I had to pick one element that characterized this period of history, it would be needless bloodshed in the interest of personal or institutional power and agency.

Bear with me. As the players, you are not the British, you are not the Russians. You are local leaders, attempting to manipulate forces that are bigger than yourself. If you make good investments, if you ally yourself with the right powers, if you move with great savvy — you still can lose. To paraphrase something I hear in Doctor Who, you might win, but nobody wins for very long. You can do everything right, and still lose the game, because power and hierarchy are shifting sands. The feeling of a good game of Pax Pamir is thrilling, but it is also a reminder and a warning about history. War is not a game, and the people who thought it was created horror in the lives of their “pieces.” It’s a commentary that you can’t help but participate in by playing.

That, my friends, is a hell of a thing. That is art.

I really enjoyed this excellently written review.

PP2E is likely to attract anyone who is a fan of John Company, An Infamous Traffic or some of GMT’s COIN series. Although I’ve never played the first edition, apparently there are some definitive improvements with this edition that let the game shine.

This was a fantastic read. Thank you.

This is, by far, the best review of a (war)game I have read.

I just purchased this game and will keep your thought about it when discovering it.

Thanks again