“It was a dire situation: Commies to the left of me, traitors to the right, and there I was, stuck in the middle with the Team Leader, only one working laser pistol between us. There was no time to waste; he was getting that shifty look in his eyes. Was he a Commie traitor too, or were his inadequate leadership skills causing him to suffer from low morale?

With his loyalty in question, my duty as Happiness Officer was clear: I pumped him full of Thymoglandin and sent him screaming towards the enemy. His noble sacrifice saved me, allowing me to complete the mission entirely by myself, and I only regret that it was his very last clone so that I could not thank him personally before reporting him for desertion. Oh, Friend Computer, I shall forever appreciate the many rewards you’ve given me for this successful mission, and I look forward to serving you alongside my new team.”

Ever since George Orwell’s iconic sci-fi treatise on totalitarian government was published, the year 1984 has taken on a cultural resonance that far outstrips the reality. It proved to be just another year, eventful but not unusual: the Bell System was broken up, Reagan won re-election, the Raiders won the Super Bowl, Apple introduced the Macintosh personal computer, and most of the Eastern bloc countries withdrew from the summer Olympics. Yet it’s only fitting that 1984 saw the publication of Paranoia, a tabletop roleplaying game that took Orwell’s dystopian nightmare (and others like it) as inspiration for one of the greatest settings imaginable: the harrowing and hilarious world of Alpha Complex.

Welcome, Citizen

It’s hard to imagine now, in an era of RPG abundance, but a look back at the RPG world as it stood in the dawn of 1984 shows a much sparser landscape. Dungeons and Dragons was still the undisputed king a decade after its debut established the field, and while there were a growing number of worlds on offer for the curious, D&D’s influence was clear on many of them. Decades of fantasy, sci-fi, and superhero media found expression in new titles; a few publishers even managed to get the licenses for big names like Star Trek or James Bond. Still, the order of the day was for serious long-term campaign play, in which a ragtag group of underdog adventurers teamed up to save the day from the shadowy forces of evil.

Paranoia was the exact opposite of that.

The Computer Is Your Friend

Paranoia is a game of dark humor that occasionally — or frequently, depending on the group — veers into absurdity. The player characters aren’t misunderstood heroes; they’re bumbling idiots with little power of their own, caught in a rigid hierarchy that pits them against each other. Ruled by an erratic tyrant, the PCs are ordered from place to place with little explanation and tasked with resolving problems far beyond their understanding or capabilities. Petty infighting and character death are not just possible; they’re actively encouraged. This game isn’t meant for min-maxers: players aren’t even allowed to know the full rules, nor are GMs expected to strictly follow them.

The key to making all this work is the setting. When Paranoia was first published, the Cold War had been looming over the world for more than 30 years. The game builds on that history using some stock science fiction tropes, imagining a future where humanity has been either partially or completely eradicated (presumably by nuclear war). Before this great cataclysm, a number of bunkers were created to preserve the future of the human race.

One such bunker is Alpha Complex. Its overseer is The Computer, a perfect satire of Cold War programming. The Computer is erratic, manipulative, authoritarian, demanding, and above all paranoid: its overriding fear is that Communists, mutants, and traitors are lurking everywhere within its otherwise spotless enclave. To defeat these (potentially imagined) threats, The Computer enlists the help of select citizens called Troubleshooters who, as the name indicates, find trouble and shoot it. Of course, if nebulous ne’er-do-wells have infiltrated Alpha Complex, then it stands to reason that some of the Troubleshooters might also be Communist mutant traitors…

Stay Alert!

And therein lies the brilliance of Paranoia. Everyone in Paranoia is a nefarious character of some kind (either a mutant or a member of a secret society, though usually both) who wants to subvert or support The Computer’s assigned mission. Every player character has multiple reasons to come into conflict with the other PCs or with various non-player-characters. Unlike most roleplaying games, Paranoia is predominantly competitive. Completing the “quest” is optional at best and impossible at worst, so the joy of playing comes from finding new and devious ways to eliminate your rivals without being caught. Two particular design innovations allowed Paranoia to play unlike anything that came before it.

First, the GM is strongly encouraged to be an active participant in stoking conflict, usually by taking on the role of The Computer and antagonizing the PCs. Whenever the PCs start to make headway, The Computer might interject to make sure they’ve filled out the proper paperwork, question them about their hygiene rituals, redirect them on a wild goose chase, or create situations for PCs to take covert actions against each other.

Failure to satisfy The Computer’s whims almost always results in termination (read: execution), which leads to the second creative decision: to keep the body count high, characters are not normal human beings but force-grown clones raised in vats in the bowels of Alpha Complex. Each PC gets a six-pack of clones to start, so as each clone gets killed, its replacement gets delivered to the team and the game continues.

Trust No One!

The production of Paranoia took as many labyrinthine twists as a standard Troubleshooting mission. The first edition was published by West End Games in 1984, designed by the trio of Greg Costikyan, Eric Goldberg, and Dan Gelber. It made an immediate mark and received an Origins award the following year, leading to the second edition in 1987.

However, West End Games would experience some financial troubles, and the original design team was forced out prior to the game’s so-called Fifth Edition (really the third, a gag which undoubtedly confused many consumers) in 1995. This zanier edition of the game was not nearly as popular as the previous two, and West End was in the middle of planning another when the company was forced to declare bankruptcy. Much of the later West End material would be declared non-canonical “unproducts” by designer Allen Varney because of the sillier tone and lack of focus on Alpha Complex, though this obviously does not prevent players from using these products.

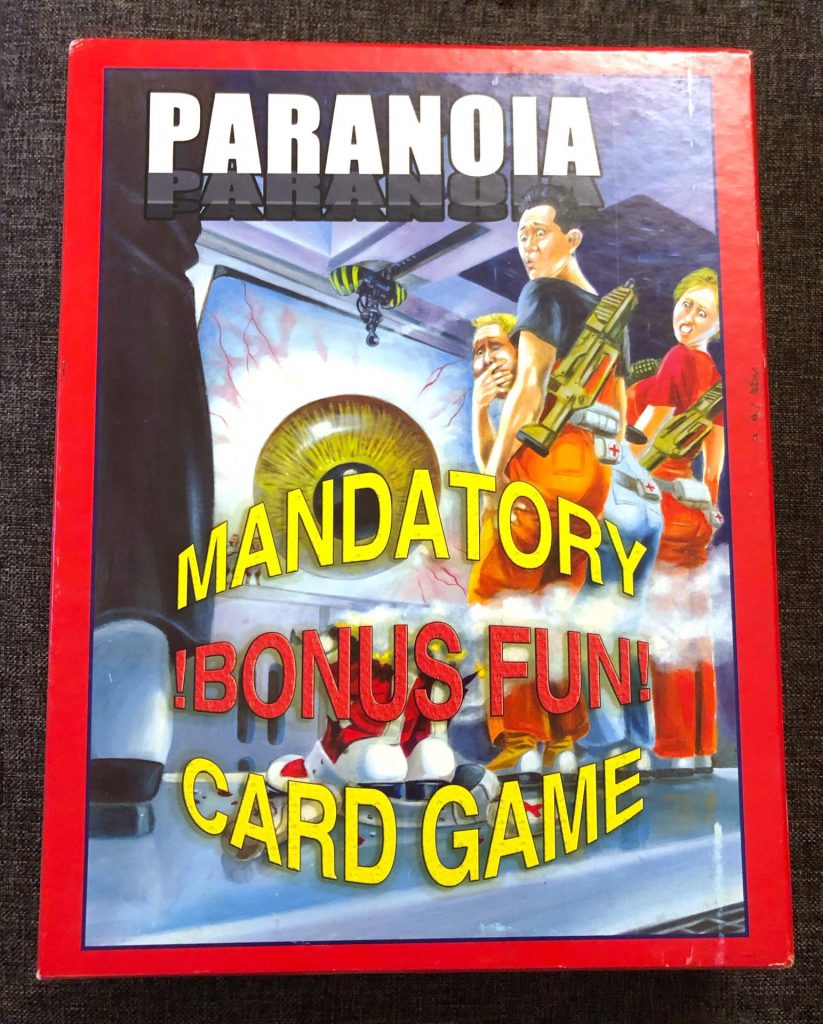

Eventually, the original designers were able to recover the rights to Paranoia and, alongside Varney, released a new edition — Paranoia XP — through Mongoose Publishing in 2004; the XP would be dropped after complaints from Microsoft. This edition largely returned to the game’s roots, but perhaps the best update was its formal introduction of three modes of play: Classic (darkly humorous and moderately lethal), Zap (wacky and very deadly), and Straight (serious, survival-focused campaign play). These tonal designations are incredibly useful and can be applied to many other roleplaying games, like Fiasco, to help clarify player expectations at the outset.

After Paranoia XP came the 25th Anniversary Edition in 2009, which hewed closely to the XP products. In 2014 a new edition of Paranoia was funded through Kickstarter, though it would not be released until 2017. The new edition was helmed by James Wallis (Once Upon a Time and The Extraordinary Adventures of Baron Munchausen), assisted by members of the original design team as well as freelance writer/designer Grant Howitt and famed game reviewer Paul Dean. This edition focuses on accessibility and ease of play, updating the classic Paranoia experience for a new generation of Troubleshooters.

And Keep Your Laser Handy!

While Paranoia has seen a surprising number of editions over the years, each with their own pros and cons, it remains an iconic game that provides gamers with an experience unlike any other. As more modern games like Apocalypse World have dabbled in semi-competitive play and rules-light one-shot games like Lasers and Feelings have proliferated, it’s easy to see how Paranoia continues to influence RPG design to this day. And with the release of the official Paranoia PC game in November 2019, it’s clear that Alpha Complex isn’t going anywhere.