Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

I love Abstract Strategy games. Put me in front of a board with a minimum of setting or storyline, add in some pieces and a good set of rules and I’m a happy guy. Abstracts like Tactigon, Hokito, Tak, and the wealth of games in the Pyramid Arcade are generally easy to teach due to their minimal rules.

I also love it when an abstract surprises me. With Mur, it was the round board round board—a round board with three rings and eight intersections per ring.

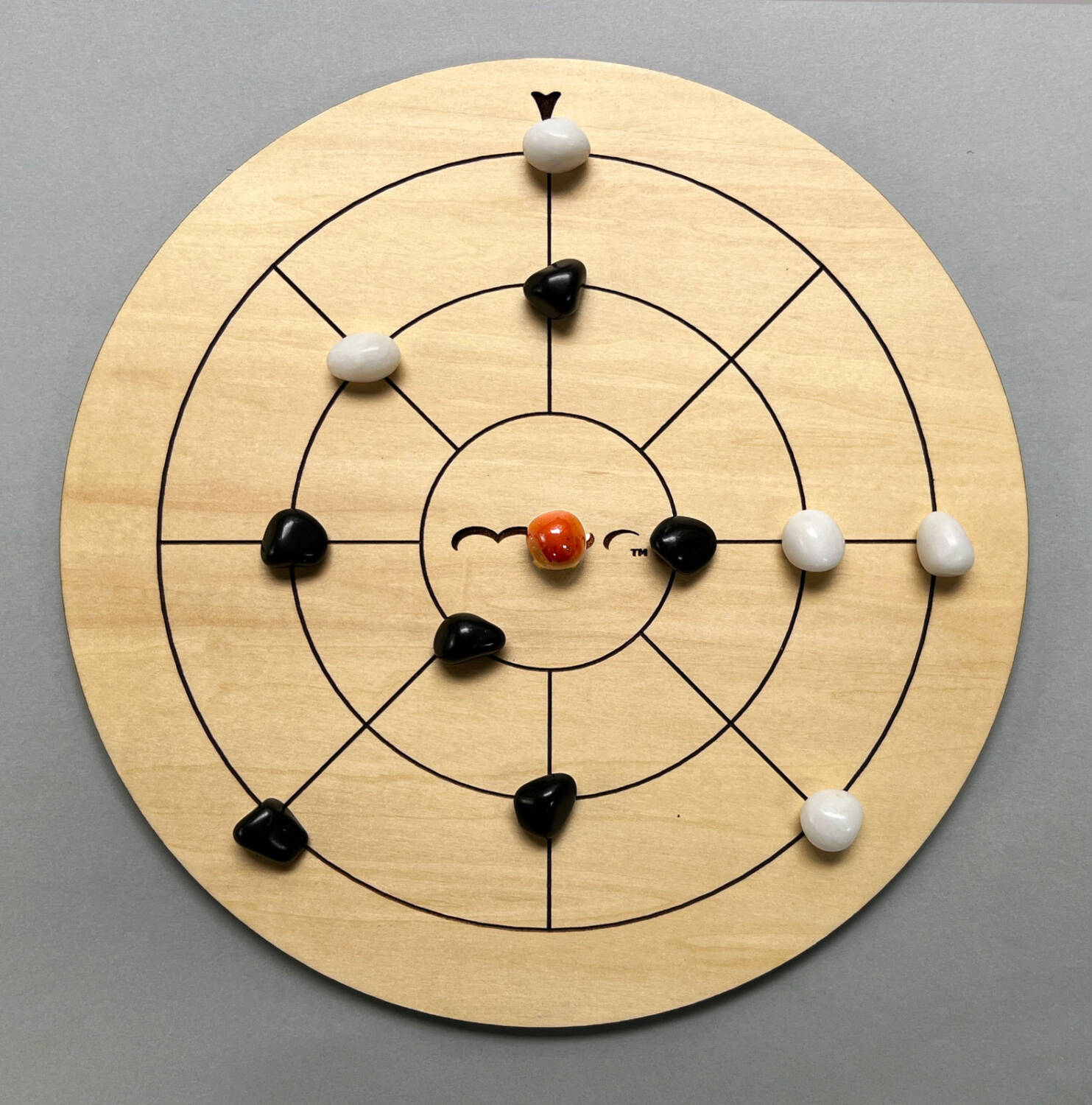

Add in two winning conditions—surround the red Mur Stone or three of your opponent’s stones over the course of the game—I wanted to learn more about Mur.

Setup

To set up a game of Mur, place the wooden board between the two players.

Take the red stone and place it in the center of the board.

Then divide the remaining stones into two groups, with one player taking white and other taking black.

And you’re ready to play.

Playing the Game

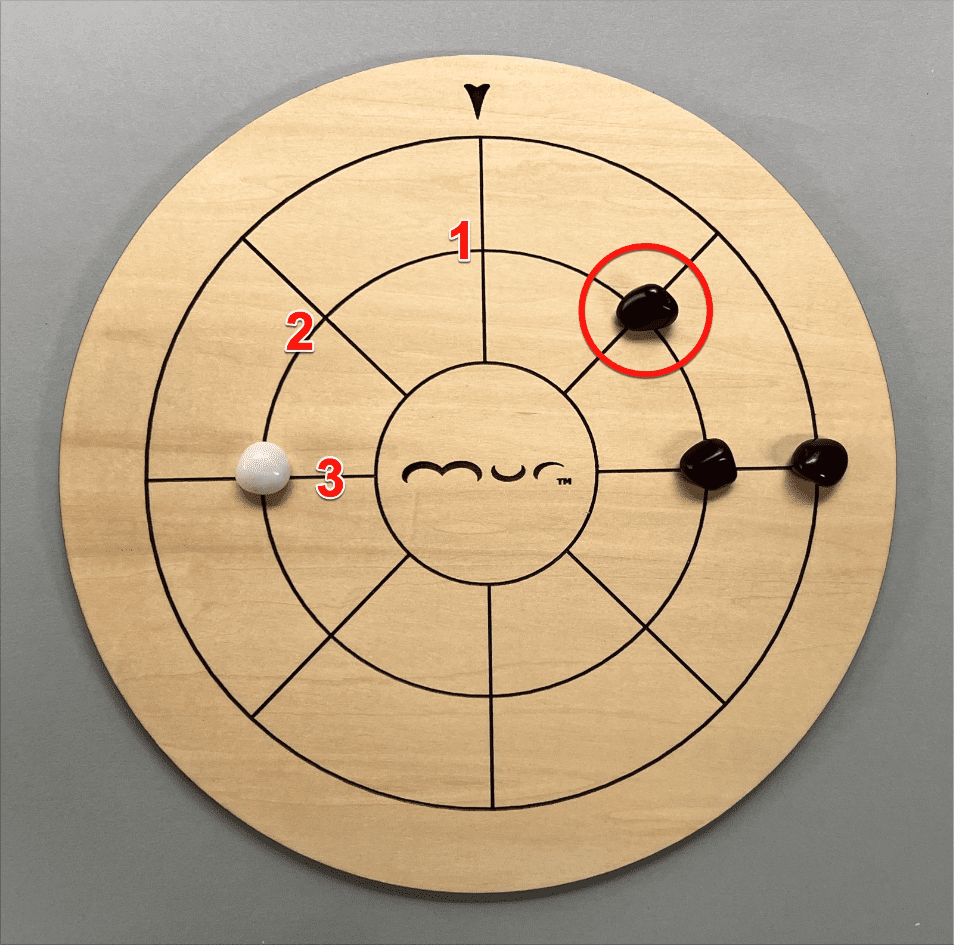

On a turn, players can either move one of their seven stones from their supply onto an empty intersection of the board; move a stone from one intersection to another; or, if forced to, remove one of their stones from the board.

Understanding these three options is essential to playing Mur well.

Placing a Stone

Placing a stone on one of the unoccupied intersections sounds easy enough—and it is. However, there are several things to consider when placing a stone. Much of this has to do with how stones behave when in connected groups, so let’s move along to…

Moving a Stone

As I said, one of the ways games of Mur are won is by surrounding your opponent’s pieces. This means having four of your stones on all four intersections adjacent to your opponent’s stone. Chances are, you won’t be able to simply surround an opponent’s stone by placing stones around it. Not only will your opponent see the obvious attack on the piece, but they’ll also be able to move the piece away from the barricade you’re trying to build.

When moving a stone you can move along the straight lines to an empty space or along the curve of the ring. However, the distance you must move is dictated by the number of stones connected to it by following the diameter or circular lines. A single stone can only move one intersection; one in a series of two stones must move two, etc.

While placing and moving stones on the board, you need to be aware of not only how many connections/spaces you can move, but how many connected stones your moved piece will be adding to. If you’re moving a stone into a group of four stones, you’ll need to be sure one of those pieces can then move five spaces on the board or you’ll be limiting your options.

If a stone is ever moved along a diameter such that it would be pushed off the board, the movement continues, except back in the opposite direction.

But what about the Mur stone? It starts the game in the center of the board. You’re not going to be able to surround it while it resides there—the center position has eight adjacent intersections and you only have seven pieces. So, how to move it?

Provided the piece you’re moving comes from a connected set of stones with fewer members, it can Knock, or move a stone that’s part of a higher number of ‘connected’ stones. A Knocked stone must always move in the direction the knocking stone was moving, stopping on the first open space.

Just as with moving, if a stone is Knocked off the board, the knocked stone simply continues its path in the opposite direction, landing on the first vacant intersection.

For purposes of Knocking, the Mur stone is always considered to be in a group of four. Thus, it can be Knocked by a stone in a group of three, two, or one.

Removing a Stone

If a stone is ever surrounded on all sides (four sides for the inner circles; three on the outer circle), that player’s next turn must be spent removing that stone from the board. That’s the entirety of that player’s move.

However, this is for single stones only. Groups of stones cannot be trapped.

Trapped stones go back into the player’s supply of stones and can be returned to the board on their next move.

Ending the Game

After the third trapping of a player’s stones or once a player has surrounded the Mur Stone, the game ends. To set up for the next game, remove any stone that’s in the center of the board and place the Mur Stone there. Leave all the other pieces in place and begin the next game.

The rules state that games of Mur are typically played in two sets of six games, with all pieces being removed at the end of the sixth game. Black makes the first move in all odd numbered games and white moves first in the even numbered games.

Considering Mur

Mur has a lot of things going for it. The board presents a circular, enclosed world, while the rules regarding movement and Knocking means knowing when to place, move, or Knock a piece is an essential part of any strategic approach to the game. To that end, Mur is a very think-y abstract, exactly the kind of game I love.

The games I’ve played with friends have all taken a bit longer to explain than many other abstract games because the rules are a bit more complicated. Unlike games of Pente or Abalone, games I’ve taught without saying a word, Mur requires verbal explanations with on-the-board examples to make sense.

Those games have all been enjoyable challenges. Competition for the Mur Stone is always at the periphery of my strategic thinking. Moving and/or Knocking stones so they improve my standing and flexibility on the board is something that has developed (often through my own bad moves) over games.

Despite this, I do have some hesitations concerning Mur.

The initial rules that came with my copy were very difficult to follow, much less make sense of. Designer Desmond Davies graciously agreed to a Zoom session with me to go over the rules and provide some examples of game play. That helped to clarify much of the game to me, but when I tried playing it afterwards, I quickly ran into situations that weren’t covered in the rules.

Since that time, Davies has put together a series of instructional How to Play videos, available at his Mur Federation website and his YouTube channel. Watching these videos will help you gain a much better idea of how Mur is played.

Still, I have to admit that I don’t understand the reasoning behind a true ‘game’ of Mur taking two rounds of six games. That’s a big time commitment for a new abstract.

There does seem to be some advantage to the black player in the first game. (Remember, black moves first in the first game.) Black’s initial attack on the Mur Stone can lead to some predictable gameplay in that initial game, with white having to go on the defense almost from the start.

That advantage is supposed to be mitigated by the way each of the other games starts in that series of six games—again, by leaving all the current pieces where they are and moving the Mur Stone to the center of the board. For me, I’m not sure this really works. In my games, the winning player most often had the superior command of the board in general. By starting the next game with that control of the board left largely intact felt like putting the losing player at an immediate disadvantage.

I assume if I played more and put extra thought into how the endgame positions would form the starting positions of the next game, this disadvantage might be better diminished.

Which leads me to my final point: Does Mur have replayability? Yes. Have my gaming friends asked to play it again? Not so much. Friends who have enthusiastically asked to play other abstracts again right after the first game ended were more reserved about Mur. The most common responses have been that the game was interesting but, given the complex rules and the small board, they felt they’d need to play it a lot to get better at it.

In that regard, Mur may not be for the casual gamer. Mur is more like Chess, Go, or Shogi in that it’s a heavier game best suited for gamers willing to invest hours exploring and studying the game.