Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

Mille Fiori is an apt title for Reiner Knizia’s newest big box release. Not just because Mille Fiori is thematically concerned with glass blowing, to the extent that this heavily abstracted game is thematically concerned with anything, but also because millefiori is a glass-making technique that involves fusing individual glass rods into a cohesive whole. Mille Fiori is a fused bundle, five different minigames that, taken together, form a coherent board game.

The Rods

The fundamental action of Mille Fiori will be familiar to anyone who’s played 7 Wonders or Sushi Go!. Players simultaneously choose a single card from their hands, then reveal those cards in turn order. While the cards in 7 Wonders become your empire, and the cards in Sushi Go! become your sushi plate, the cards in Mille Fiori are but a means to an end. They allow you to place a tile in the corresponding section of the board, where the real action happens.

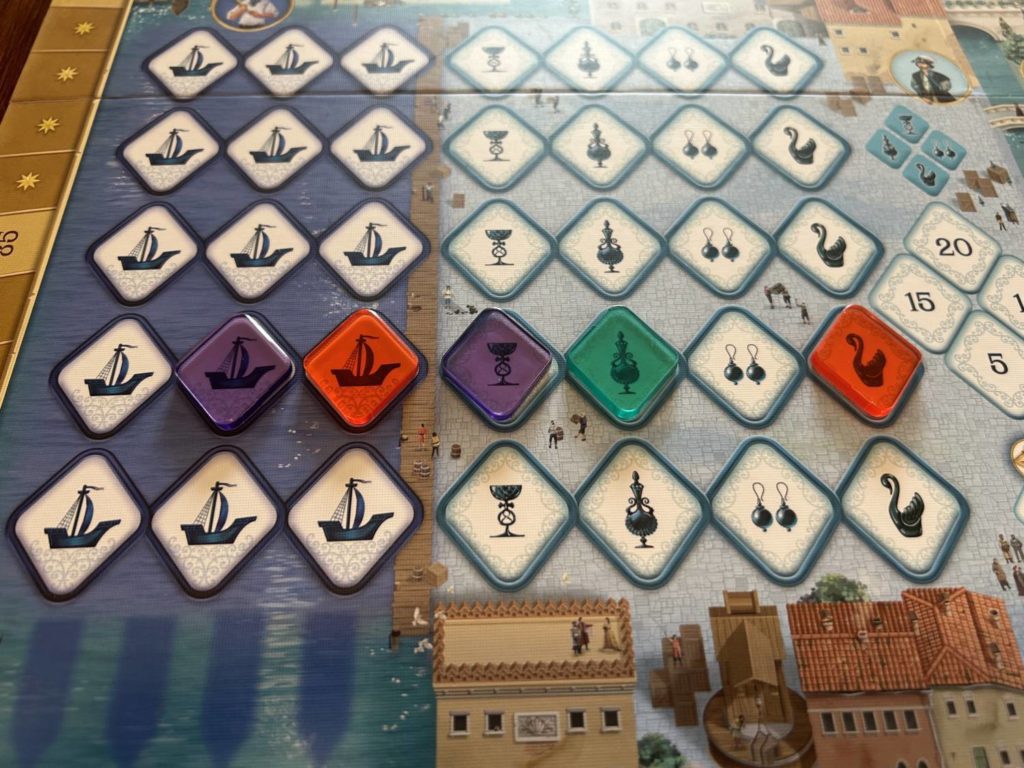

And what a board this is. I wouldn’t call it beautiful, it looks a little too much like the math problem the game effectively is to truly be beautiful, but it is unquestionably alive with color, and I love that. The color scheme Schmidt created for this game—the Devir publication is physically identical to the German release as far as I can tell—is vibrant yet gentle, full of pastels we don’t usually see. When you add the translucent player tiles, those diamond-shaped panes of glass (plastic), this game as having toy appeal.

What happens when you place a tile is going to depend on where you place it. It is an unusual thing to have to begin the teach for a Reiner Knizia game by saying, “It will seem like there’s a lot more to keep in mind here than there really is,” but Mille Fiori requires just such a qualifier. Because each section of the board has its own rules, you’ll have to navigate panicked looks, sweaty brows, and hesitant eyes screaming “I thought you said this was simple.” Worry not, it is pretty simple. In fact it’s exactly like Ganz Schon Clever. Various abstract scoring rules happening simultaneously are initially hard to keep in mind, but within a round, everyone gets it.

When you place in the Workshops, the orange section of the board, you score points for any of your own tiles adjacent to the tile you just placed.

The Residences, the purple row, fill in from the top to the bottom, and you score the number you cover with your tile. If your new tile is immediately adjacent to one or more tiles in your color, they score again.

The Townspeople, the teal and seafoam green sections to the lower right, build upwards. Tiles placed in the bottom row score one point, middle spaces earn you three, and the top spaces are worth six. The catch here is that you cannot place a tile until both tiles beneath it have been added. Tiles you place among the Townspeople continue to score as other players add tiles to that section.

The last two sections, Trade and Harbor, are the only two that interact with one another. Trade is organized in columns of matching items. Earrings, glass swans, goblets, that sort of thing. When you place a tile on an earring, for example, every tile in that column scores one point for every earring with a tile on it. Let’s say your tile is the third one placed on an earring, and another player placed the first two. You score three points, and that other player scores six. The next time a player places an earring, they will score four, you will score four, and that other player will rack up eight.

The Harbor is the only section that doesn’t always immediately score you points for placing a tile. Tiles sit in waiting, ready for when a row of three is completed. Once that happens, all three tiles score points based on the number of Trade spaces with tiles on them in the same row. If you read that sentence a second time, it’ll make sense. Below the Harbor sit lovely little glass (plastic) boats, one for each player, that progress along a track as you play tiles to the Harbor. These boats score you points.

The Trade and Harbor sections are my favorites. The way they interact feels very thematic, surprisingly so, and as a result they come alive in a way that the rest of the board never quite manages. I also find that decision space richer, because there are more ambiguities to deciding what the best move is. I would kill for a Trade and Harbor spin-off set in the Mille Fiori universe.

There are two other site-specific rules to keep in mind for each area. First, there are the bonuses. Four of the five sections give ever-decreasing bonuses to players who accomplish a specific task. The task differs from section to section, of course, but it boils down to “Cover one of each symbol.” The bonuses introduce a racing element to the early game, encouraging players to focus on a specific region if the cards allow. The first player to receive a given section’s bonus immediately scores 20 points, then 15, 10, and a measly 5 for fourth. The bonuses can really add up if one player is allowed to bogart them, though that doesn’t make the player unbeatable. I lost my first game of Mille Fiori despite outperforming the table in bonuses by a significant margin.

The final rule in each section has to do with action chaining. If you fulfill the right conditions in any section, you get to play a card of your choice from the market next to the board. If you play astutely enough, that card may allow you to once again fulfill the proper conditions to once again play another card from the market, which may once again…you get the idea. Much of the game’s tactical satisfaction comes from spotting and seizing opportunities for large chains, and much of its skill comes from playing to avoid setting up such opportunities for others.

It’s Fiber, It’s Good for You

This is, in case it wasn’t already clear, an insalata di punti if ever I’ve played one. Knizia has taken a Stefan Feld point salad and slathered on a low-fat dressing of player interaction.

I say “low-fat” because I find Mille Fiori more interactive in theory than it is in practice. The theory is great. There’s the tension of wondering which card the person before you in turn order is going to pick, if they’ll take your spot, and there’s the tension of deciding what cards to pass on to the person after you. Is there a card that would be better for you and another that would be extremely good for them? Which do you take? That’s juicy stuff.

Neither of those tensions amount to much, however, due to the fairly low odds of the card deal working out to allow it. The manual includes an alternate ruleset that has players pick and play their cards in turn order, meaning the second player would see the first player’s card before choosing for themselves. I, personally, like the drama of knowing you’re locked in for better or worse. That change puts all the focus on mathematical decisions. There’s a certain type of player for whom that arrangement would be deeply appealing.

By the end of Mille Fiori, player scores will be in the 200’s. There will have been some cursing, there will have been some laughs, there will have been gleeful accumulation of points. It plays quickly, both in feel and actual playtime. Mille Fiori is a perfect game for groups looking to find a compromise between the constellatory calculations of the Feldian and the approachability and interpersonal dramatics of the Knizian.

Add Comment