Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

Modern Euro-style strategy game design is in full swing.

I know that some of our peers in the media and content creation space have bailed on the concept of medium-weight Euros. These types of strategy games are sometimes getting too complex without matching the elegance that similar games possessed even five years ago. However, 2024 has been a banner year for games that shake up the formula just enough to warrant a second or third look.

A case in point: Men-Nefer (2024, Ludonova), the newest design from German P. Milián, who has given us Bitoku, Bitoku: Resutoran, Sabika, and Bamboo. Bamboo was lighter fare, a game that ultimately proved to be more interesting as a production than a decision space.

Both Bitoku and Sabika proved resilient within my gaming circles, particularly with the turn mechanic of Bitoku and the rondel element of Sabika. I’ve held onto both games because I had so much fun exploring each one, even if I think they will be really hard to table on a consistent basis. You know greatness when you see it, right? For the players in my game-o-sphere, Milián is clearly onto something.

Milián’s success continues with Men-Nefer, a thematic sibling to Sabika, right down to a box cover that looks eerily similar. That’s funny to me, in part, because save for the boat components in both games, I never felt like I was sort of playing Sabika during any of the turns I took playing Men-Nefer. The games don’t feel similar in any way, and the theme feels a bit pasted on.

But the action system in Men-Nefer is fantastic and the reason to give this a spin. This was the only Milián game I have tabled that did not garner universal praise from the players who joined me, so let’s talk about what worked for me and what might not work for you.

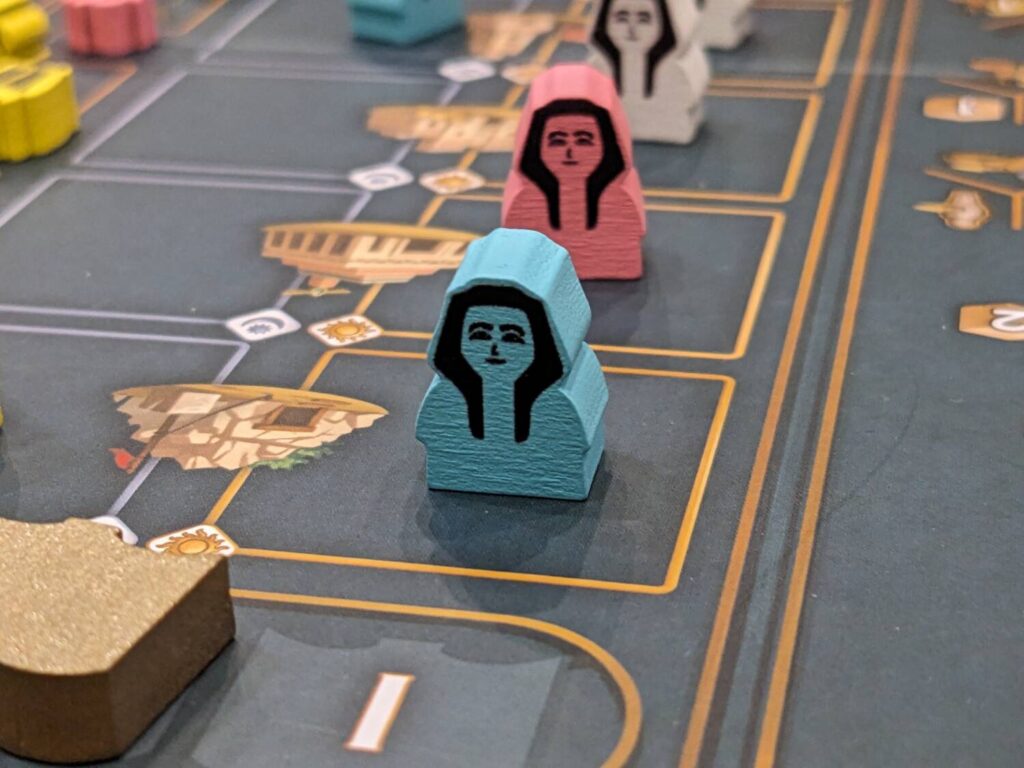

“Deploy the Mummy”

Men-Nefer is a 1-4 player worker placement game, with a recall mechanic and set collection elements that drive each turn. Over the course of three rounds, players try to score the most victory points by taking a variety of actions, such as advancing boats up a river to collect contracts and boost income, placing sphinx tokens on one-time bonus locations, and deploying sarcophagi meeples in a tomb to trigger ongoing scoring bonuses at the end of each round. You’ve got priestesses, feathers, baskets, a papyri mini-game where matching symbols provide a boost on certain tracks, and four different pyramids that are slowly assembled via actions taken by the players.

Even though there’s a short, snappy 15-minute AI-voiced teach video sponsored by the publisher, my experience has told me that Men-Nefer is a difficult onboarding experience. Across three plays—two games with two different groups at four players, plus a solo game against the automa—I was somewhat surprised by the lack of intuitive play generated by my opponents, especially because the majority of these players are very experienced Eurogamers.

I think the lack of intuitive turn-taking is tied to the details behind each action, and not in the simple administration of each turn.

Players can only take three different actions:

- Resolve an action tile, then place an apprentice (worker) on the main board

- Slide an apprentice to the right in its row, triggering a bump up one of five tracks and taking an action

- Take a new action tile from a market row, which triggers a minor action and seeds the player’s action tiles for the upcoming round.

It might have been my second or third turn of the first multiplayer game of Men-Nefer, where I started to see its magic. (Well, it was magic to me.) Even though each player will take 27 turns during the course of the game, the turns are relatively quick, but each action gives you a tickle more to do than just “place worker here to take three wood”, or something similar.

Here’s an example: You remove an action tile that gives you a boost of three spaces on the river. Each player has four boats, and can split their movements with action points allotted by the action. The movement system for boats is fluid, as pieces move through small cities to collect contracts that will score at the end of each round. Boats can’t share spaces with other boats owned by the same player, so everyone has to solve a brief mini puzzle when taking this action.

So, that’s the first half of this particular turn, moving then activating these boats. Then, that player has to select a row in which to place their apprentice. Men-Nefer offers a lot of flexibility—there’s no rule that says you have to place all three workers, then move all three to their right-hand spaces to boost tracks, then take three new action tiles. Usually, players react to what’s available on their turn and move accordingly. The first turn of each round must be to place a worker, but after that, who knows? It was cool to mix up when and how to take new action tiles back to the board. (There’s another mini-game here as well, when players take back action tiles in one of four symbols to trigger another minor bonus.)

Men-Nefer has loads of timing tension. Placing an apprentice in an empty space has no additional cost. But if two other apprentices are there already, that’s going to cost three food, and food is somewhat limited early on. You might want to wait to pick a certain row until other players have slid their apprentices out of the way. You might need a certain action tile right now, and if another player is also hunting for that same symbol, suddenly you are in a race. Turn order is vital in Men-Nefer, and the game uses a scoring mechanic tied to favoring players farther behind to dictate who goes first in future rounds.

How Many Mini Games is Too Many?

Men-Nefer has, by my count, eight different tracks. Most are tied to a specific mini-game, but all those mini-games will find a way to make themselves essential at some point during the game. (The winner in each of my three plays dabbled at least a little in every track, a good thing in a game where one rightly should worry if there’s any extra fat on the game’s design.)

The heavy track elements led to a good amount of chatter during my plays. “This feels like a low-scoring version of a point salad,” one player suggested, in a game where the winner scored 74 points. “There are a lot of tracks going on here, maybe too many…it just feels like the game could be better if there was less going on,” complained another.

Men-Nefer could probably get away with one less activity, particularly because there are not one, but two sets of pyramids that can be built by players, triggering different sorts of bonuses. The small pyramid area feels like something that could have been dumped without much of a hit to the overall satisfaction I found in my games.

But finding ways to touch each part of the game was exciting to me, without a major hit to the rules overhead. That’s because Men-Nefer features so much tactical play. Sometimes, I found myself focused so much on matching the symbols on my incoming action tiles that I didn’t care at all what was on the tile. That meant future rounds started sub-optimally, but in games like Men-Nefer (similar to my experience with games like Inventions: Evolution of Ideas), all the actions you need are somewhere on the board, it just takes a little while to find them. So even if you’ve got suboptimal action tiles, you’ll find a way to work out something.

A second surprise: scanning the board did not lead to as much analysis paralysis as I was expecting. Just saying out loud that a four-player game of Men-Nefer has 108 turns scared the hell out of me when I was doing my first multiplayer teach. But that first game only took about two-and-a-half hours. My second four-person game (with different players who were also new to the game) was closer to two hours.

So, you’ve got some real meat on the bone, there’s plenty of interaction, and downtime must be spent calculating where you can go and what you can legally afford to do on your next turn. If anything, I was never bored.

And for every reason I enjoyed Men-Nefer, I could see where others might step away from the table.

In the wrong hands, Men-Nefer is a three-hour game, maybe longer. That’s too long for the decision space. The iconography here is rough, to the point where players were still asking about what each icon meant near the end of each game, even in areas that those same players had spent their entire game focusing on. (Men-Nefer is a re-teach game, if there ever was one!) Players who don’t manage their resources well here will really be in a bind. For instance, the pass action in Men-Nefer is brutal, forcing a player to move an apprentice to a new location, then skip their action and take three food.

In a world with a billion games coming out every year (it feels like a billion, even if the real number is closer to 1,500 or so), Men-Nefer is a poor place to start for a gamer building their collection. It is a game for a serious gamer, one who is committed to playing it more than once, because the first play is the kind of learning game that will keep a few people coming back again and again while others say goodbye forever.

Pure of Heart? Purists Only

Men-Nefer has cemented my feelings about Milián as a designer—the guy is the real deal, someone who I will now aggressively seek out when it comes to future designs. (And it will shock no one if Men-Nefer gets an expansion, so I’m sure this is a project I will throw money at in the future!)

I love Eurogame tracks as much as the next guy, but the real selling point for Men-Nefer is the action tile selection process. This, combined with the lack of structure around which of the three actions a player can take almost every turn, made Men-Nefer a blast as a decision space.

The production here is ridiculous. I’m not sure I’ve played a game this year with a list of player components as varied as what is included here. Some of the pieces, such as the feather token and the small baskets that priestesses use to mark a player’s territory, are so small that they are loudly inviting players to lose these components at a gaming cafe. (Don’t let your small children near this game, people!)

The toy factor helps balance these player components, because the game is a looker. The board is a bit too busy, but it is complemented by components in bright colors, a large white pyramid that looks dope by the end of each game, and a surprisingly simple series of set-up steps. At the outset, I was worried the game’s small pieces and variability would make it hard to set up, but I consistently got everything prepped in less than 15 minutes by myself.

A few things about the game didn’t work for me. The first is criminal, to the point that I will put the finishing touches on another article as a result—Men-Nefer should have never left the production facility without individual player aids. There are no words anywhere in sight, so the icons do all the heavy lifting here. And there is just one single-sided player aid to pass amongst the players. Instead of using the back side of the aid to detail each contract, the contracts are defined on the back of the rulebook instead, with the back side of the single player aid used to provide information in Spanish (Ludonova is a Spanish publisher.)

I can’t even begin to understand why this decision was made and, naturally, players spent most of our multiplayer games passing the rulebook and single player aid around. How much would it really cost to add three more player aids to an already-pricey Euro, people?????

Second, I think the game is probably going to live in my collection as a three-player-max experience. Four players was fine, and I loved the competition for space, but I’m lucky—most players in my circles move quickly through their turns. I would never play Men-Nefer with three strangers at a convention. The solo game (complete with its own rulebook) is a great way to learn the game’s systems and the score in my only solo game was quite close.

The game is intended to be a four-player game, though, so I’m torn on the preferred player count. I know that Men-Nefer prefers a four-player count because the game features a generic apprentice mechanic when there are less than four players. This ensures that there are always extra costs to using certain spaces in a round.

The building tracks are my other minor beef with the game. I have still not seen a game where more than one of the four pyramids was completed, and the bonuses for adding pieces can sometimes feel minor. There is a very handsome income scoring mechanic for players that invest heavily in building the larger pyramid, but in a weird twist, the player that went hardest on that track in my first game lost by 20+ points because he didn’t balance his play strategy across the other tracks.

I think the design would feel leaner and still offer the same decision space if there was one building track, and not two.

Otherwise, I thought Men-Nefer was fantastic. It’s important to note that Men-Nefer was definitely not a winner for four of the six other players who joined me for review plays, so it’s possible that I will ultimately be the outlier here. For now, I’m going to bask in the Egyptian sun of this game and sit patiently while Ludonova cranks out an expansion in a year or two!

I really enjoy this game and I have to add, we have had the opposite experience with the pyramids. In our four games, the winner has always followed a heart/feather strategy by going hard on the pyramids in the early game. I think the balancing in the game is ultimately going to come down to the players.