Is there anything left to be said about Love Letter? Doubtful, but let’s give it a shot.

The Simplicity of Love Letter

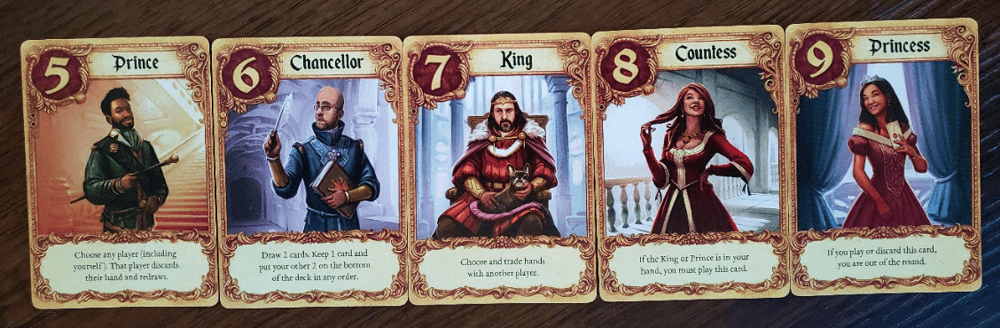

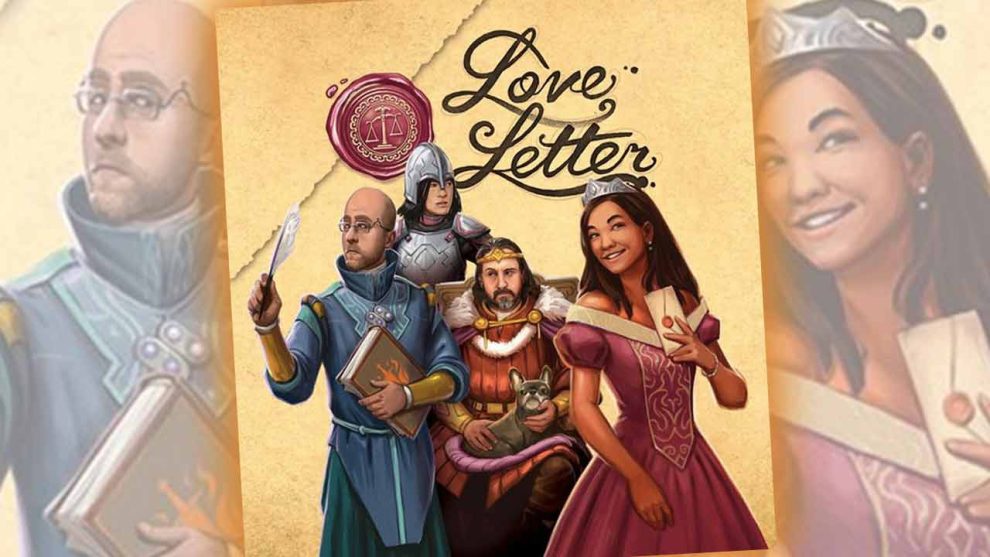

Love Letter (2019) consists of a deck of 21 cards and a handful of resin Favor tokens. The cards are numbered zero through nine, with each card bearing the name and image of a character along with instructions for the card’s play.

After setting aside a single, random card that will not enter play for the round, players each receive one card, with the remaining cards forming a face-down deck. On a turn, players draw a single card and then choose which card to play, face-up, to the table, resolving its effect.

The object is simple: be the last remaining player or the remaining player with the highest card in hand once the round is complete. The player who wins the round receives a Favor token before the cards are gathered and dealt once more. Once someone reaches the number of Favor tokens prescribed for the player count, the game ends and someone gets happy.

Players itching for the classic 2012 sixteen-card experience can remove the Spies and Chancellors, valued zero and six respectively, along with one Guard and carry on as normal. Players itching for more and more and even more can hit the market for Love Letter: Premium Edition or any of the bevy of official or unofficial thematic re-designs available in stores or on websites the whole world over.

The Genius of Love Letter

I taught Love Letter to some of my family just the other day while dinner was in the oven. Herein lies the genius of Seiji Kanai’s now ubiquitous classic. I pulled out the velvety bag whose size, rich red color, and golden scales suggest simplicity and elegance. Though a non-gamer might try to find the words, there is nothing here to offend—of course they’ll play! As I laid out a few of the cards to teach the rules, the charm and ease of play rose to the surface.

Keep in mind this has all happened in less than 90 seconds.

I dealt the cards and, seemingly without warning, we were playing. I took the first turn because I knew the game best (but also because I had most recently hand-written a letter), and then it was time for the two new players to take action. Guards. Of course. Guards are easy and you only really need to make a random guess. My wife played the Handmaid, keeping the interaction among the rest of us for another turn. Second round, I eliminated one with a guess of my own before the Countess betrayed the other. In the end, my wife played the Baron and showed me her Princess. Of course, she also had the only Spy, so she was quickly up two Favor tokens to none all around.

I could do that for each round, and you’d have an entire written testimony of Love Letter in fewer words than a typical review. That is the genius of the now-classic card game. Easy entry and memorable exits.

The Nuts and Bolts of Love Letter

One of the most important mechanics in Love Letter is the removal of a single card from the deck each round. Imperfect knowledge creates just enough risk to elevate the game’s simplicity to a place of tension. That tension is over in a flash, but it is enjoyable enough to get a bit excited for the next deal. I am reminded of another game in this micro-genre—Council of Verona—which thrives on the same principle. There is always a bit of chance in taking a certain tactical line because you can’t be sure the needed cards are in play. Fate is mitigated only by the fact that the round is over in minutes—you can always just try again.

The hard line of the original game arc is softened by the addition of the Spy and the Chancellor. The Spy—numbered zero—opens a second avenue to Favor tokens that heavily relies on timing and creates the outright necessity of targeted attacks since only one player with a Spy can score. At a value of six, the Chancellor allows players to arrange and rearrange the end of the deck, and, more importantly, to remove the Princess from the hand without immediately facing elimination. I love these characters and their impact on the game—adding layers of intrigue without adding time or unnecessary complexity.

The Ubiquity of Love Letter

Though efforts existed before 2012, the decade of Love Letter’s popularity has witnessed an explosion of micro-creativity. Multiple publishers have explored this genre of intentional limitation, with one—Button Shy—existing solely to elevate such pocket-sized creative endeavors. I am frequently amazed at how much is possible with so little. (Though not every title on the list is quite as micro, check out our Top 6 Killer Fillers, or for perhaps the most micro of them all, take a peek into In Vino Morte)

The theme of Love Letter never mattered much, which opens the door to a unique sort of customization in the tabletop industry. Peruse the Files portion of the game’s listing on BoardGameGeek and you’ll find that fans have uploaded cards for countless other intellectual properties. Official versions are out in the retail aether emulating Batman, Infinity Gauntlet, Star Wars, The Hobbit, Princess Princess Ever After, Adventure Time, and Lovecraft. With a bit of free time and a color printer, you can play any sort of cottage-industry Love Letter that interests you. The mechanics are complete and function independent of the images on the cards, much like every -opoly game in the mall—if you can find a mall, that is.

If I speak of my appreciation of Love Letter, it’s not quite the same as that of my favorite games. It is a more utilitarian affection. As a game, it is just so very useful.

When I’m heading out for a social evening, I grab Love Letter as if it were a reflex—even if the evening has nothing to do with games. I’ve stuffed Love Letter in my wife’s purse for formal affairs, just in case there’s an unbearable lull at the table. It plays at pizza shops, weddings, and picnics as easily as it does at game night. I’ve played with young and old alike. I’ve never met an extra-terrestrial, but if I did I’d be perfectly comfortable offering Love Letter as a welcome to the planet.

In fact, it wouldn’t surprise me if they pulled out their favorite version first.

Add Comment