When I find a game I enjoy, or better yet, one my family enjoys, I try to build on that experience. It’s not always as simple as perusing the “Fans Also Like” portion of a game’s listing on BGG. After all, the fact that I like Shakespeare is in no way predictive of the fact that I like Altiplano (which appears on that list), nor does the mechanical composition of either build an effective bridge connecting the two. It just so happens that I like both, as do others, enough so to warrant being connected via BGG’s algorithm.

BGG also offers title lists sorted by mechanics, but, to quote the great Patches O’Houlihan, that’s about as useful as a poopy-flavored lollipop. A list of 6,365 Area Majority games is not the most efficient path to finding a game that I will enjoy like I enjoy Petrichor.

I’m grateful that we try here at Meeple Mountain to build bridges. Our step-ladders link games that seem to have a natural progression. Our topics aim to find games that are thematically linked. But the lists are hardly exhaustive at this point—they take time and experience to develop.

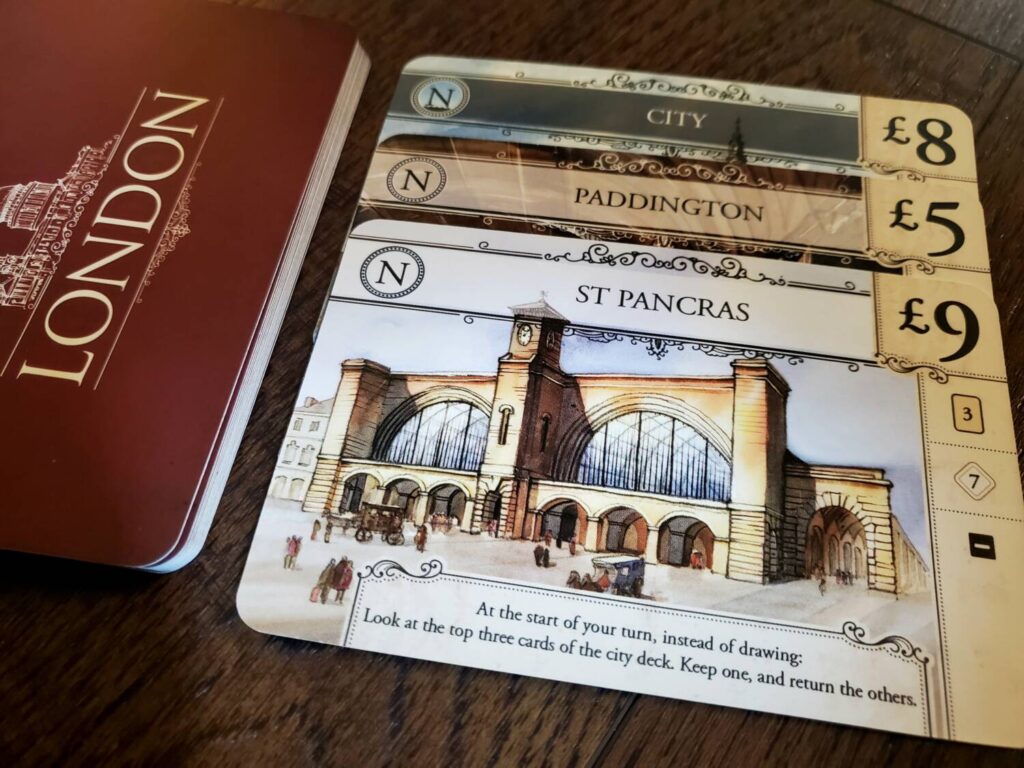

My family’s unexpected love of The Flow of History left us looking for a sequel, or a prequel, or a game in the same ludological universe. The Jesse Li design is a small box civilization game, an oxymoron of worthy note. We loved the stacking cards, the tight economy, the thrill of overcoming. Oh, and that one-hour playtime. In this case, the traditional channels yielded a possibility. London, a Martin Wallace design, boasts stacks of cards and a tight economy in a city-building affair. Better yet, it promised a level of awkwardness that might just match the strange personality of The Flow of History. The Second Edition seemed an intriguing match on the surface—so I took the plunge.

Lon-doing

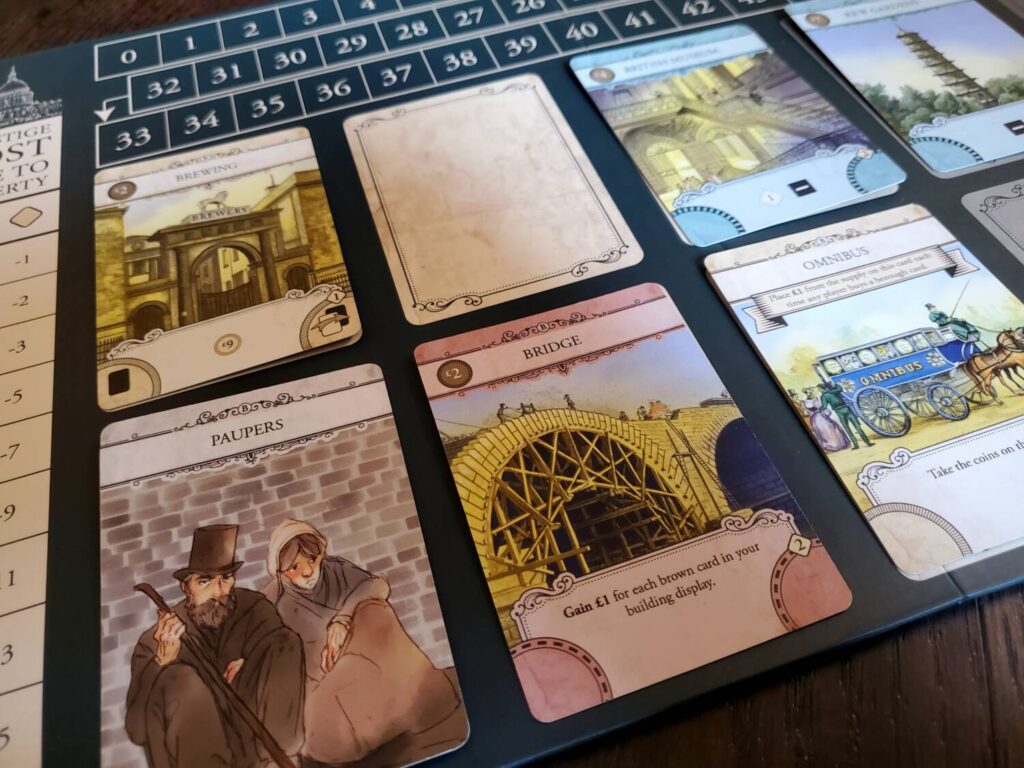

Players build a city, an evolving engine of City cards supplemented by a collection of Borough cards. In London (Second Edition), attention divides between two sides of a scale, a balance of success—cash and prestige points—and poverty.

After drawing a single card, each turn is a choice of four options: Draw three cards, Play cards into the City engine, Run the City engine, or Purchase a Borough. Most cards in the city are single-use, flipping to their backside after bestowing their benefits. Of course, stacking cards then becomes a major part of the game. The greater tension comes from deciding how many stacks are worthwhile.

After running the City, players collect poverty—black cubes and discs—equal to the number of stacks in their city plus the number of cards in their hand. The entirety of the game then includes an effort to reduce poverty or mitigate its often-rabid increase. There is a temptation to incorporate cards that reduce poverty in the city tableau, knowing full well that the immediate after-effect of running the card is taking on more poverty. The feeling of futility borders on crippling at times.

The hope is that an influx of cash will enable the purchase of worthy causes. Boroughs come with immediate benefits—cards, prestige points, and decreased poverty. Some come with effects that linger until another Borough is purchased and stacked on top. Some may come with effects that accompany running the city, though they are not necessarily pleasant.

The remainder of the cash is needed to play City cards—the more impressive the card’s effect, the higher likelihood that it will require a pound or two to add to a stack. The one consistent cost in playing City cards is a discard of a matching color card to an open market. This market is constantly shifting and changing according to player activity.

Contributing to the poverty trouble is a smattering of Pauper cards in the deck. In a harsh societal message, these cards serve no purpose but to remain in hand, subsequently generating poverty every time the economy attempts to thrive. There are discard opportunities, an even harsher reality that has players tossing them aside, occasionally in exchange for cash or prestige points.

The questionable air

London (Second Edition) operates like a lung, breathing in and out. Players build their cities, working out a suitable number of stacks that will generate a sufficient income while minimizing the pain of poverty. The hope is to dwindle hand size in preparation to run the city, which then inflates the coffers and the scoreboard, only to then begin again. Cards flip, turns and Boroughs bring cards, and the pursuit of efficient spending continues. In and out, in and out, with varying degrees of avoidance with regard to poverty.

When the deck runs out, players take to the scoreboard one last time to determine a winner. Every card that entered a stack, whether it was flipped or simply buried beneath another card—always an option—yields its endgame points. Not every card scores, however, adding a layer to city decisions throughout the game. Leftover cash scores, unpaid loans (which are available and payable on any turn, and which bring even more poverty to the engine) lose points, but the real rub is poverty.

The player with the least poverty discards the whole lot. Every other player then discards the same number of cubes before deducting points based on the quantity remaining. In this way, poverty gets the last laugh, sometimes reducing a prominent city-builder to a dejected has-been.

Success never felt so…terrible

London (Second Edition) is a strange economy. Sharing a deceptive liberty with the likes of QE, the game invites players to build a city of any size. There is no stack limit, but defying the bounds of common sense will bring impoverished devastation. The money will feel good, but money practically evaporates while stacks are forever (along with their prolixity of pain). The tension is palpable from the first run of the city. I am beyond impressed with the way this design generates an allergic response to success. It feels great to build the city. It feels terrible to run the city, especially as a newbie to the system. Inevitably, players begin to experiment with poverty reduction among the city cards, only to find their wheels spinning out of control. Playing cards to reduce poverty, which then bring in poverty is, well, unnerving.

There also exists a fascinating learning curve around effectively managing the size of your hand. Ideally, the city runs with nearly zero cards in excess. A light bulb sparks to life when players realize that shedding one card to trigger certain city effects is not a penalty at all, but rather an opportunity to relieve one more inconvenience, often a human inconvenience called Pauper, before collecting a jackpot. London (Second Edition) implores you to live on a razor’s edge, a dubious paragon of calculated efficiency.

Loans are available throughout the game, but we’ve not really sought to utilize them. Perhaps we’ve missed a strategic opportunity, but funds can grow thin as the game wears on, making the prospect of repayment (at a hefty premium) less realistic. Maybe the best idea is a quick infusion of funds early, but there’s nothing wrong with trying to develop income within the system.

At the end of the day, avoidance rules the landscape. I’ve watched poverty spiral out of control to the point of resignation. But I’ve also watched master classes in pain management that resulted in landslide victory. Learning to control this most unusual variable is the heart and soul of London (Second Edition).

Old world charm

The deck is stacked in three progressive groups that cater to each stage of the game. Certain cards reward patterned Borough purchases. Others reward the color patterns in your City tableau. Knowing these cards are coming is helpful, but it’s no simple matter to have the money in hand when the opportunities spring. Sometimes you plan a particular sequence only to find a wholly enticing card derails your entire life, or that someone overloads the discard market, eliminating the card you were hoping to draw. The highs and lows are emotive and non-stop.

Speaking of the deck, the art in this edition of London is wonderful. The trio of Natalia Borek, Mike Atkinson, and Przemyslaw Sobiecki deserve all the credit in the world for capturing a perfectly matched set of prints for the game’s setting and mechanics. I’ve not seen cards this over-stocky since Fantastic Factories. But they lend an air of solidity and satisfaction to the old world charm.

If I were to criticize a component in the mix, it would be the classic, primary color player pawns. I would have taken chunky discs in muted burgundy and blue or something similar over the less dignified pieces. As is, they don’t stack and they break the aesthetic. If I were to criticize a second, it would be the snaking scoreboard, but that’s not exactly a universal opinion.

Lon-done

I’ve seen online grumbling about the pain of poverty, but I adore Martin Wallace’s inclusion of the troubling variable. The game is thoughtfully unique for it. Every card is in use for every player count. I might also see folks chiding the sameness, but I think that very sameness is the centerpiece of the game’s battleground. The fascinating result is that the game essentially lasts as long with two players as it does with four.

Overall, London (Second Edition) is a perfect follow-up to The Flow of History. The awkwardness, the reward of familiarity, the fight for coins, the evolving landscape, the length. These are the qualities that we were looking for. What we received, in addition, was a much simpler rule set and a less complicated iconography without deadening the decision space. Like The Flow’s catty scratching and cliffside ending, London’s allergic tendencies might keep some from ranking it highly. But there’s little doubt both have personality. Not every game needs to shower resources. It’s OK to withhold a meal or two.

In case it’s not obvious, I like London (Second Edition). When I find the next game in the progression, you better believe I’ll start writing that step-ladder article.

Add Comment