Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

A Nearly Verbatim Transcription of the Author’s Most Recent Teach of Lacrimosa, Which It Is Not Necessary to Read in Its Entirety (Feel Free to Skim) but Does Offer Illuminations Regarding the Author’s Issues with The Game

Pt. I: Tutto è disposto

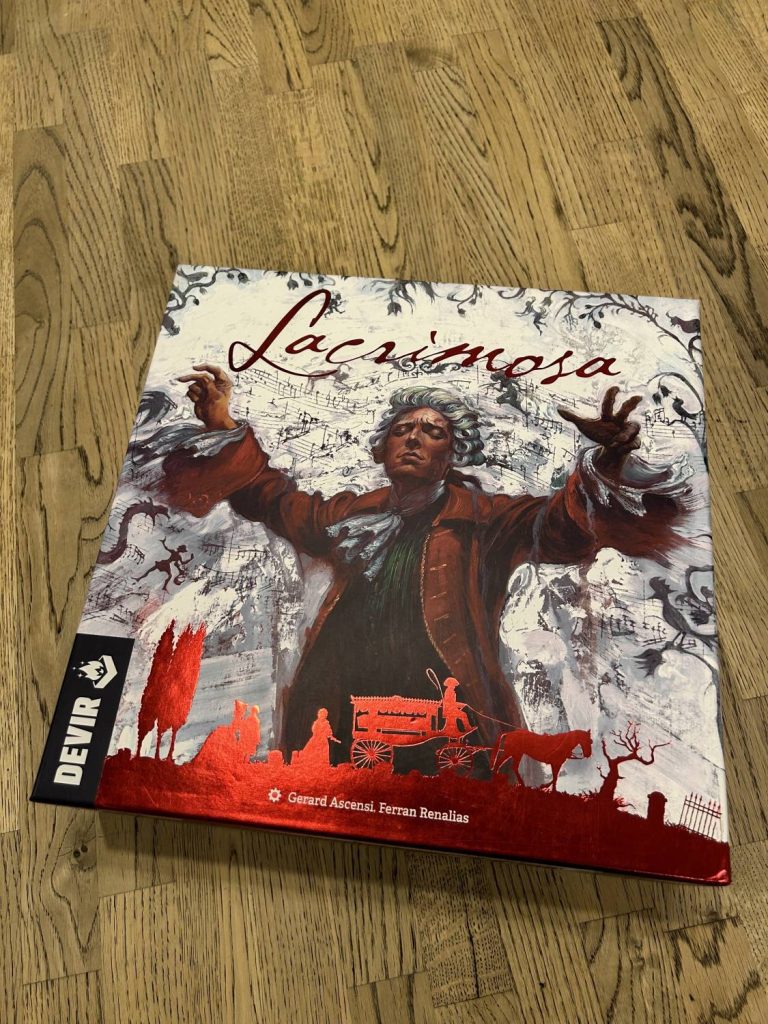

Alright, everyone. Tonight we’re gonna play Lacrimosa. It’s got a lot of Euro stuff, it’s got a bit of deck building, I think this group will like it. First thing, yes, it’s a beautiful box. Devir does a wonderful job with the production of their heavier games.

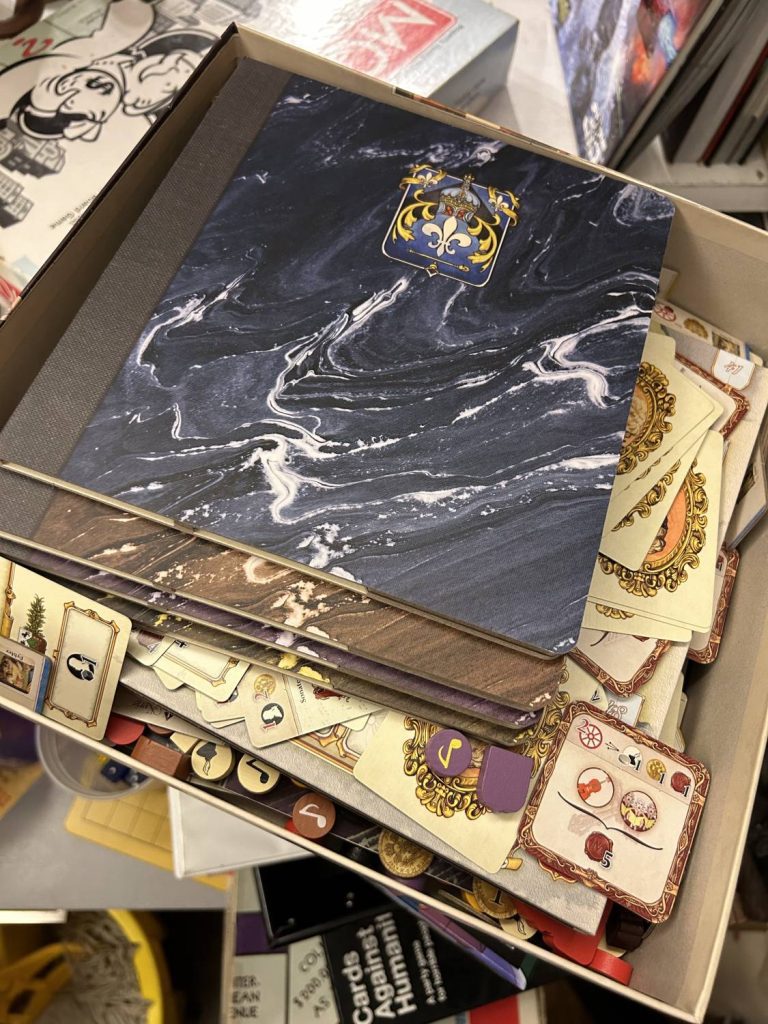

Before I explain this, we should get it all on the table, that’ll make the teach easier. I’ve got jobs for everyone, if you don’t mind. Mary and Susan, can you help me separate these cards by, I think the game calls them Eras, by the little roman numeral on that red shield in the middle of each card? Look out for the player crests, too. We’ll each get a set of those as our starting cards.

Sorry for this, there are no bags in the box and there are, as you can see, a lot of parts. I meant to organize everything after my last game, but I didn’t get a chance.

While we’re sorting out these cards, Mitch, can you find the tiles for these two composers, and organize them by movement name? By movement na— by the words in the fancy font. So there’s the Kyrie, the Sequentia, the Deus Irae, etc. Yeah. And then stack them by—those icons on there are the cost, the more it costs the lower it goes in the pile.

Bryan, your job is to put out a bonus tile in each city. The rest can go in two piles in the upper left, next to the deck of cards. Yeah, exactly.

Pt. II: Crudel! perché finora

Now that that’s done, let’s get cracking. So, the theme of Lacrimosa. Mozart’s dead, he just died, and you are nobles competing to have the greatest influence on the completion of his Requiem Mass, which was unfinished at the time of his death. You’re also trying to endear yourself to his widow, Constanze, because she’s going to, like, add your name to the sheet music or something.

Look, this is the last time I will mention the theme, because the game becomes more confusing the more you think about it. Lacrimosa is a series of levers that y’all are going to spend the next two hours pulling. Don’t think about what’s being represented.

I know this board looks a little overwhelming, there’s a lot happening here. The good news is I promise the game is relatively straightforward once we get started. Your turn is wicked simple. You’ve got this little deck of nine cards, which I’ll give each of you now. Susan, I’m going to borrow your cards and your board to illustrate.

At the beginning of each round, you draw four of these cards. Then you’re going to pick two. See how you’ve got these larger windows at the top of your board and these smaller windows at the bottom? First, you’re going to pick a card for its action, the bigger picture at the top of the card, and slide that into the larger window.

I know, it’s super-satisfying.

Then you’re going to pick another card for the smaller picture at the bottom, and slot that in the corresponding lower slot. The bigger picture at the top is the action you are going to do right now, on this turn. The smaller picture at the bottom is resources you’ll get at the end of the round. Just to repeat that, the big picture is the action, you’re doing it immediately, the small picture is resources you’ll gather before the next round. Makes sense? Okay.

The good news is, that’s an entire turn. When you’re done, you draw two more cards, the next person goes. Once it gets back to you, you’re going to put an action card in the second top slot and a resource card in the second bottom slot, do the action, and then that turn is done. Same thing happens again, though please note that for your final turn you will only have three cards to choose from. You will see every card in your deck during every round.

Pt. III: Crudel! perché finora

There are five, only five, actions. Each action corresponds to one section of the board, so let’s go down in order. First, we have these two. The game calls them “Document Memories” and “Commission an Opus,” but we’re going to call them “Buy an action card” and “Buy a music card.” Up here at the top of the main board, there are these seven distressingly identical cards. See how some of them are pushed up and some of them are pushed down? Believe it or not, that matters. The cards that are pushed up are Actions, the cards that are pushed down, with the fancy ovular frame in the middle, those are pieces of music. You may recognize some of the titles.

Let’s look at buying an Action first. You slot the book and candle into your board, that means you want to buy one of these. The cost for Actions is printed straight onto the board, and you can see that cards are less expensive as they approach the right edge of the market. So let’s say I want to buy this card, which costs one Ducat, the currency, and this symbol means it costs one resource of my choice. I pay those, and then the new card replaces the card I slotted into the bottom section of my player board for this turn. That card gets removed from the game. We pop it straight into the box, which is how we ended up in that setup mess to begin with as it should happen. This does mean that you’ll get the resources listed on the bottom of the card you just bought for the next round.

Related: you’ll never have more or less than nine cards.

Now let’s look at buying Music. These have their cost printed on the top of the card itself, and there’s a little additional cost printed on the board. You pay the cost, you get whatever number of victory points are printed in the upper right corner, and then you add that piece of music to your collection. There are four different kinds of music in this, they are represented by different pictures. Those will matter from time to time.

Either way, when you buy a card, you remove it from the market and slide all cards towards the right, then place a new card in the leftmost empty slot. Cards do get less expensive the longer they’ve been on the board, broadly speaking, but please also note that the four rightmost cards will get burnt at the end of each round.

Next let’s talk about Performing and Selling Music. These two actions are performed using this card, which shows the Queen of the Night on stage [ed. At this point, one of the players pretends to sing a few bars of opera], yes, exactly, and this parchment scroll. When you perform this action, you can choose whether you want to perform or sell whichever one of your pieces you want. Each piece of music has a cost for being performed or sold–the resource is called “Talent” but we’re calling them Mozart Busts because that’s what the image is and why is Mozart’s talent a resource that I am accruing to spend later? It doesn’t bear thinking about, it doesn’t retain any water. So you spend that resource and you get, if you perform the piece, the amount of money shown on the card. Then you rotate the card 90º to indicate that it has been performed this round.

If you choose to sell, it’s a similar idea, but you’ll get some combination of victory points and permanent improvements to your income for each round. Also, the card gets handed to me and goes into the Box of Pain. Please note, you cannot perform a work and then sell it in the same round. Not allowed, no-no.

Pt. IV: Non so più cosa son, cosa faccio

The next action is Travel, which is this stagecoach. Mozart starts the game in Salzburg–I don’t think this is the late Mozart, I think this is Mozart in the past?–and you use Travel to move him around the map. You can move him as far as you want, so long as you can pay the total coin cost for the route. Each city has a little action tile in it, which can be activated by paying the number of wagon wheels, Mozart’s favorite pasta, shown. You only activate the city where you stop, you can’t activate a bunch of tiles along your way. After you pay the wagon wheels, the tile is removed from the board. Empty spots will get refilled between rounds.

The last action, this fancy cross, is, thematically, you’re paying these composers to work on Mozart’s mass. Practically speaking, this is a little area control mechanic wrapped up with some engine building.

You’ve got these note tokens on the right side of your board. If you do this action, first thing you need to do is look at the bonus tokens at the bottom of each of the five sections of the mass. Some of them give you resources or points one time, immediately, while others give you a recurring bonus. These two give you a bonus point every time you buy, perform, or sell a piece of music of the matching type, and those last two let you immediately repeat the depicted action any time you do it. If you have this tile, for example, you can travel to a city, pay to get the bonus, then travel to another city and do it again.

Then, when you decide which tile you want, you’ll take one of the music notes from your part of the board, it has to be for an instrument part that exists in that movement, and place your token with the correct side up. One composer is represented by eighth notes, the other by sixteenth notes, and at the end of the game…no we’ll come back to that in a second.

So if you want the tile in that section from the top composer, you’ll need to put your token with the eighth note side facing up, you immediately get the bonus listed next to where that token was on your board, then you have to pay the cost shown on the tile you want. These get more expensive as you get deeper in the pile, so earlier is better.

At the end of the game, the note tokens you’re placing here will score based on majority. This section, the Sanctus, for example, whichever composer has more tokens in this section, each of those tokens will be worth six points. The composer with fewer tokens in this section, each of them will be worth three points. Each player will score for however many tokens of each they have there. Again, that doesn’t happen until the end of the game.

Last thing, I think: the resources. Some tiles and cards give you resources with a little cube, while some give you a disc. If it’s a cube, you move your marker on this track. If it’s a disc, you take one of these wooden discs. Important: the cubes will reset to zero at the end of each round, but the discs accumulate.

That’s pretty much it. You’ll play five rounds in total. How is everyone feeling?

Cosa sento!

Lacrimosa is fine. It’s bone-dry, and it isn’t particularly fun. I was reminded in several different ways of Devir’s previous big box game, Bitoku. Both games share a similar “Interlocking series of mechanisms” ethos, part of the cultural shift in board gaming towards lots of rules and bits, towards complication over complexity. Both games are, well, they aren’t a nightmare to teach, since it’s all rather systematic and you can go through it step by step, but they are a nightmare to learn, which is much worse.

Both games feature beautiful production that emphasizes unique themes, but they are themes that have absolutely nothing to do with the gameplay experience. For Bitoku, about Japanese forest spirits, the theme simply disappears. Lacrimosa is unique amongst games I’ve played for the degree to which its theme actively works against understanding the game. I didn’t bother using the theme of Bitoku to teach new players because it was faster to explain everything mechanically. I avoid using the theme for Lacrimosa because attempting to incorporate it makes the game significantly less comprehensible. That’s really bad.

Both games also feature some production choices that seem aimed at being aesthetically pleasing rather than being practical. There is no reason, for example, for the Opus (music) and Memory (action) cards to look as similar from the front as they do. They should have completely different colors for backgrounds. It wouldn’t impact gameplay in any way, and it would make it significantly easier for players to identify what cards are in the market. Instead, the designers tried to be suave, using watermarks that didn’t even register with me until my second play.

The real tragedy is that both games feature a mechanic that I adore–more on that in a moment–that gets buried under too much ancillary matter.

Voi che sapete che cosa e amor, Donne, vedete s’io l’ho nel cor.

I wanted to do a late-review turn, pivoting to what makes Lacrimosa good, but each strength is immediately followed by, well, by a “but.”

The physical production of the game is excellent. The triple-layer player boards are well made, and even handsome. The process of inserting your cards into the slots is tactile, practical, and makes the game incredibly tidy. It would be so easy for this playspace to be a disaster, and it isn’t. That said, the player boards increase wear on the cards, and some players will struggle with inserting their cards into such narrow slots.

The central mechanic of choosing two cards each turn, one for the action and one for the resource, combined with new action cards replacing whatever you’ve slotted in the resource spot, is a great idea. Because your deck will always be nine cards, you’ll see each card every round, and it’s easy to remember what cards you have. As a result, the game allows for a decent amount of planning. The exact timing of everything may shift with your draw, but you know by and large what you’ll be able to do.

Then again, Lacrimosa is such a predictable decision space that it doesn’t produce the circumstances for interesting turns. There isn’t much in the way of meaningful player interaction, so your plans can more or less proceed unaffected by the actions of those around you, and you know what cards you’ll have, so you can go ahead and do those things. The moments when the game came closest to sparking my interest were those turns where the draw didn’t quite work out, and I had to think on my feet. We’re talking at most two turns in every game, though.

If you love efficiency euros, you’ll enjoy Lacrimosa. It’s not going to become your favorite game, but you’ll have a decent-to-good time. Even if you love efficiency euros, it’s not worth seeking out in my opinion. Let Lacrimosa come to you. The theme is a welcome change from farming and war, even if it makes absolutely no intuitive sense in terms of gameplay, but there’s so much more to learn here than the decision space rewards.

I am left with the feeling that Lacrimosa is not worth the time to teach or the effort to learn. There are other, better games with the same time overhead. There are other, better games with significantly less time overhead. Last night, the group at the next table started learning Pax Pamir at the same time my group started learning Lacrimosa. We finished the teach at about the same time. One of those games offers a significantly richer decision space than the other. Ask me which one it is.

“Lack-rimosa.”

A strange specimen of a review that‘s both overcooked and undercooked. The analysis itself is rather stringy (a lot of work for a Just Another Soulless Euro conclusion) and the rules covered so meticulously that the entire essay seems to recurse.

The typical Theme/Components/Gameplay/Final Thoughts structure doesn’t help in this regard, either, but it would be unfair to burden this author with that criticism. Everyone seems to cling to it for dear life despite how tedious it is (and how perfunctory it can feel).

Also (and this is a pet peeve of mine), the Pax Pamir remark smacks of SU&SD’s irritating “Why not play Concordia instead?” and even seems a bit disingenuous. Wehrle games provide lots of handholds to get going, but they also provoke tons of rules questions and exceptions during play (which is not inherently a weakness!). Surprisingly, Lacrimosa does not.

Best of luck to you in your future work.

Thank you for reading, Hal, and for your comment. I agree that this review doesn’t work. It is too long for how little there is to say on its subject. I tried something—Hey, this game is too long for what it’s doing, what if the review were equally stagnant—and it didn’t work.

Believe it or not, I generally stay away from in-depth rules explanations in my reviews! I’m usually the one leaving comments on other MM reviewers’ drafts saying “This can be shortened down.” I don’t believe that’s what reviews are for. If someone wants to know how a game is played to that level of granularity, they can look up the manual. In the case of Lacrimosa, because I found the burden of the teach so out of proportion to the quality/depth of the game, I made a sardonic exception. That’s why I encouraged skimming in the opening title. Even I don’t want to read all of it.

As for the Pax Pamir remark, there was nothing disingenuous about it. As I sat down to teach a table of four Lacrimosa, my friend Nathan sat down with three people who’d never played Pax Pamir. Pax took maybe five more minutes to teach, and both games finished around the same time. In fact, I think Pax Pamir finished a bit earlier. With games like Pax Pamir, the rules overhead and playtime are often cited as the reasons for not playing. “It’s kind of late,” “I don’t want to learn a complicated game right now,” etc. Lacrimosa will appeal to many of the same people, but it doesn’t present as that sort of endeavor. Given that it is, I find it salient to note that Pax Pamir, even with its rules questions and exceptions, could be managed in the same amount of time. You are entirely correct to note that Lacrimosa is a smoother initial playing experience, but that wasn’t the point of the comparison.

If I were to review Lacrimosa today, I would write a different review, but that’s true of nearly everything I’ve ever written. Off the top of my head, this is the only review I’ve written that I felt I was writing *at* the game, which is not the best approach. At least I’ve tried it now, and gotten it out of my system. Thanks again for reading!

Played the game, enjoyed a lot, never felt theme going against game learn, never felt any effort, you call it so, to learn it (very straightforward yet satisfying).

I bought it later than I would, because of pricing a bit over the top, but I am glad to own it and play and enjoy. No Revolution, but Revolution is not needed everytime

I’m glad you enjoy the game, Leonardo, and thank you for reading the review.