Overview

Easily summed up in a few paragraphs, the rules for playing Keltis are pretty straightforward.

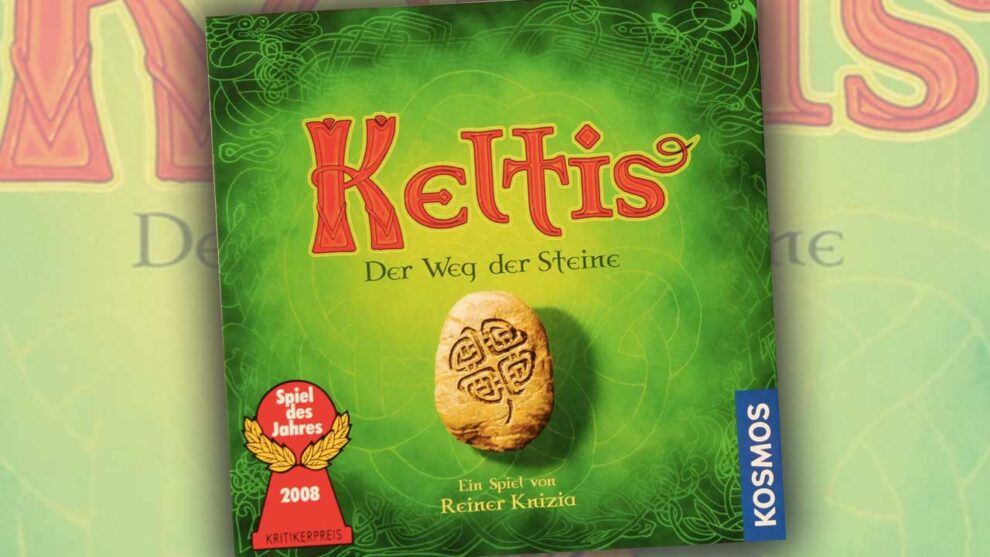

From Ashley’s excellent writeup of Keltis’s 2008 Spiel des Jahres win:

“Keltis is a followup to Reiner Knizia’s 1999 smash hit Lost Cities, and the gameplay is very similar. In fact, if you’ve ever played Lost Cities, then you’ll grasp Keltis right away. Players take turns playing cards, of different colored sets and numeric values, from their hands into their own personal displays following some simple rules:

- If the played card is the first card of the set played, a new column is started.

- The second card played to that set can be of any value.

- The value of the card (provided it is not of the same value) determines which other cards may be played into that set in the future. If the card played is of a higher value, then each subsequent card must be played in ascending value. The reverse is true if the card played is of a lesser value.

- If the player chooses not to play a card, they will discard a card from their hand into a shared discard area.

- After a card has been played or discarded, the player draws a new card either from the deck or from the face up discard area.

This is exactly the same way that Lost Cities is played, but Keltis has several important distinctions. For starters, Keltis plays up to 4 people whereas Lost Cities is strictly a two-player game. The biggest difference, though, is the central game board and the way that the player’s decisions interact with it.

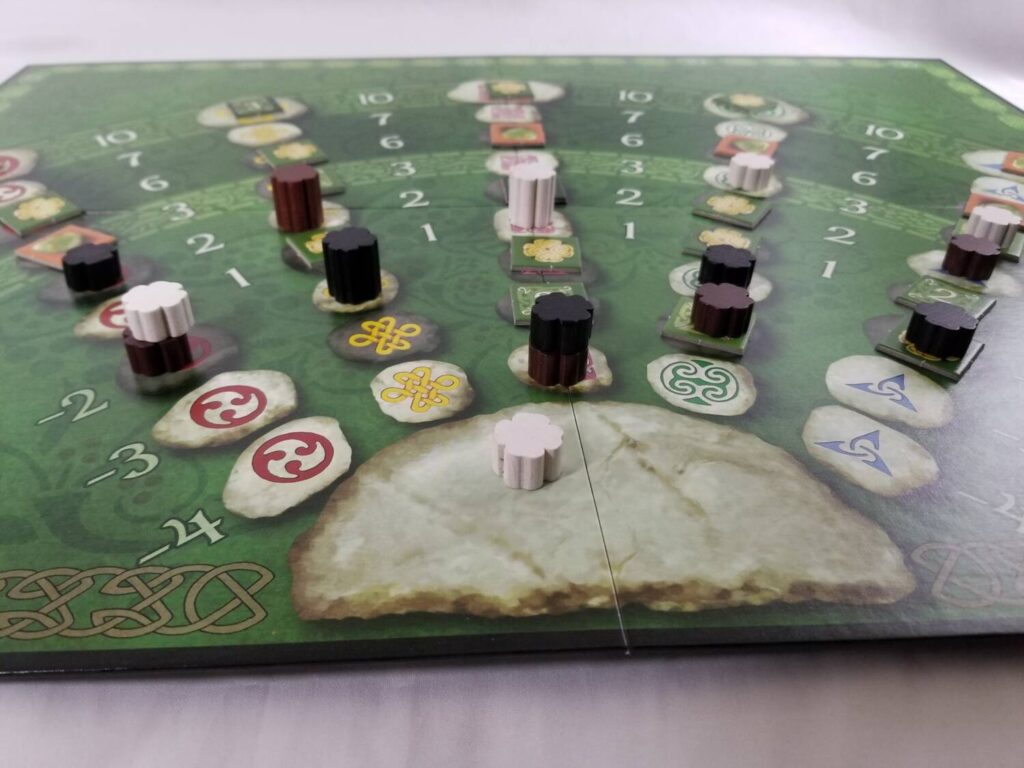

The central game board has 5 stone paths, each matching one of the sets. As the players play cards from their hands matching the sets, they will move one of their player pieces along the path (possibly collecting some bonuses along the way). The further they progress along the path, the more that player piece will be worth during the end of game scoring. Additional points are earned from some of the bonuses the players may have collected during the game as well.”

Some Specifics

Ashley’s run through of the rules is spot on. It’s almost all the information you’d need to set up the game and start playing. That being said, there are a few small details that were glossed over, in the pursuit of brevity, that are worth mentioning. For starters, in Keltis, just as in Lost Cities, it is possible to lose points.

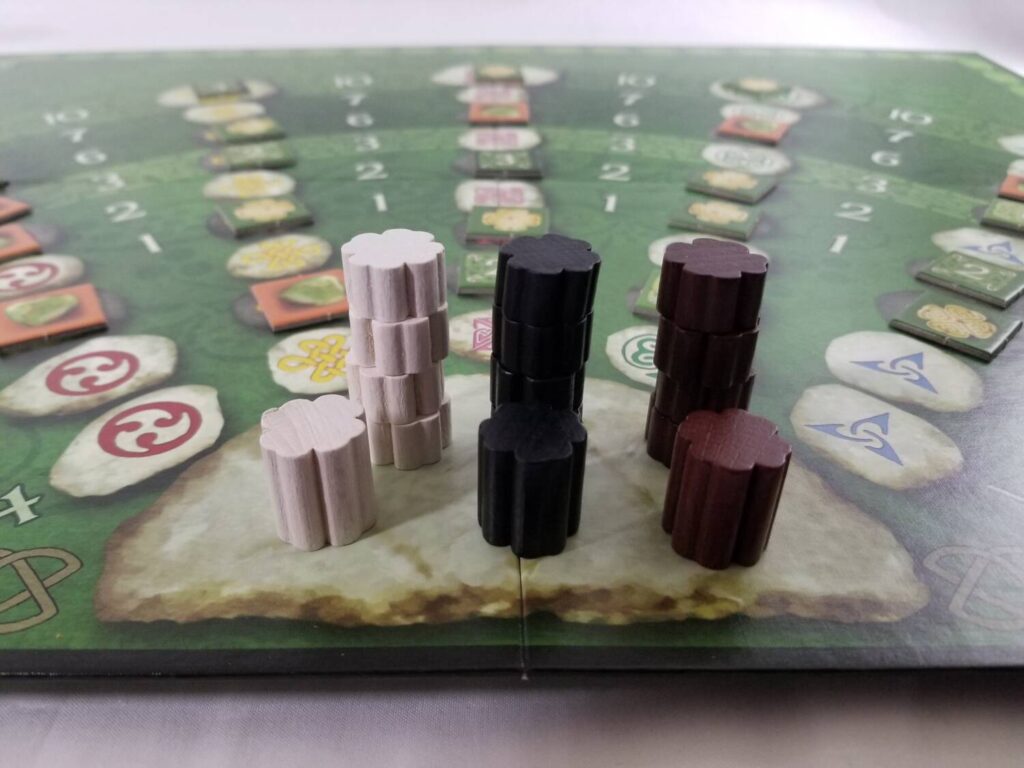

Keltis’s board is divided into several concentric rings. As each stone enters into a new ring, it becomes worth more points. Those outer rings are worth a hefty amount of points, but those first few are worth -4, -3, and -2. So, if you decide to move any of your stones out of the starting area (where they are worth 0), then it becomes imperative to move each of them at least four times if you hope to avoid a negative penalty.

These rings also function as one of the game’s two end game timers. Once the fifth stone (regardless of its ownership) has entered into one of the last three rings, the game ends immediately. The second end game trigger is if the draw deck ever runs out of cards.

Once the game ends, points are tallied up to determine the winner. Each stone earns points based on its position. However, each player also has a large stone that scores double. If this winds up in a negative space, then it’s worth twice the amount of negative points. These points are added to the points you may have earned during the game from certain Bonus tiles you may have landed on as well as points earned from certain Bonus tiles you may have collected.

There are a couple of other subtle differences. For one, in Lost Cities, once you laid down a card, you were committed to always playing a card that was higher than the previously played card. Not so here. In Keltis, the first card only indicates that you intend to play further cards of that color. The second card dictates whether future cards are going to be played in ascending order or descending order. This slight change eliminates the kinds of useless hands you’d sometimes find yourself with in Lost Cities where you’re holding nothing but high value cards.

The second small difference is that you’re not just relegated to playing a card of higher or lower value (depending on which direction you’re going), but you can also play a card of equal value as well. The card deck contains two copies of each card in each suit.

Bonus Tiles

The Bonus tiles (of which there are three types) have been mentioned several times now. So, just in case you were wondering what all they entail, here are some detailed descriptions of them:

Number tiles – landing a stone on a Number tile allows you to move your score tracker up the score track a number of spaces equal to the number printed on the tile.

Cloverleafs – landing on a cloverleaf allows you to move any one of your stones an additional space on whichever track they’re on, carrying out any bonuses from any Bonus tiles they may land on.

Wishing Stones – these are collected by the player that lands on them first. During final scoring, you will earn (or possibly even lose) points based on how many you have collected.

Thoughts

In my review of Lost Cities, I spoke at length about all the things I enjoyed about the game. All of those sentiments apply to Keltis as well. The decisions of which cards to place out where, and when (if ever) versus which cards to discard—as well as the timing of those decisions—remain the same. That’s because, by and large, they’re the same game.

In Keltis, Reiner Knizia sticks with the formula that he knows works, and then, as is his wont, he improves upon it. The addition of two extra players not only allows me to show my love of Lost Cities with even more people, but it cranks the difficulty of those decisions I mentioned in the previous paragraph up even more.

For instance, in Lost Cities, you can reasonably expect that the discard decks aren’t going to change very much before it gets back around to your turn. In Keltis, though, the board state shifts constantly, and often in dramatic fashion. That thing you were hoping to snag on your turn is most likely going to be buried beneath a pile of cards when it comes back around to you or, as is more often the case, someone else will have snagged it.

While that may seem bleak and hopeless, it isn’t. Knizia gives you the tools to overcome these frustrating obstacles. Firstly, being able to decide if your pile of cards will be moving in ascending versus descending order gives you a lot of tactical wiggle room that isn’t present in Lost Cities. Secondly, being able to play duplicate cards into your spread really helps to alleviate some of the pressure—not to mention it’s amusing when you’re holding both copies of the card someone else is obviously desperate for. More than anything, though, your greatest weapon is the bonuses.

Keltis’s Bonus tiles are what make the game stand out against its two-player counterpart, even more so than the fact that it can accommodate twice the number of players. In Lost Cities, the only real competition is for points. In Keltis, that competition for points is still there, but now some of it has been moved to the game board itself. While the actual tiles that score you points are valuable, their actual value is fairly negligible as everyone has the ability to also touch them. As far as the Bonus tiles go, these are the least impactful. The other two types of Bonus tiles, though… that’s a different story.

In every game of Keltis I have played, the quest for Wishing Stones becomes all-consuming. Possessing five of these at the end of the game can net you an easy 10 points. Getting your hands on five of them, however, is no easy feat, as there are only a total of nine Wishing Stones in the game. 10 points is a lot. But, it isn’t until you’ve played a few games that you begin to realize the true impact of the Wishing Stones. Players having only one (or fewer) of them in their possession at the end of the game are going to lose points. If you can control the flow of stones, you can also control the flow of points to your opponents.

This means you’ll likely find yourself focusing much of your efforts on paths that have Wishing Stones on them and largely ignoring others. That’s where the third Bonus tile type, the Cloverleafs, comes in clutch.

In one game of Keltis I was playing, I found myself in a situation where I had cards in my hand that could move me up the red, pink, or blue paths. Surmising my current situation, I realized that I was one step away from a Cloverleaf on the blue path, a Cloverleaf on the yellow path, and a Wishing stone on the pink path (which I hadn’t been paying a lot of attention to). So, I opted to play a card to go up on the blue path which triggered the cloverleaf. That allowed me to move up on the yellow path (which I didn’t even have cards for), triggering another Cloverleaf. Then, I used that action to move up one on the pink path, collecting a Wishing stone in the process. That Wishing stone moved me from the -2 point tier to the +3 point tier. So, collectively, because of the Bonus tiles, my single card netted me a total of 18 points—from my stones (including my big stone) moving up into different tiers added to having moved into the new Wishing stone tier. Suffice to say, it felt pretty awesome.

Keltis is chock full of these moments.

Another thing Keltis has going in its favor: if you’ve got the 2012 edition of the game, the ‘Keltis: Neue Wege, Neue Ziele’ expansion comes with it. This expansion adds a new board (printed on the flipside of the base game board), a few new mechanics, variable paths, and also introduces a set collection element into the game. Whereas the base game only features a single type of Wishing Stone, the expansion features five distinct colors. Having multiples of the same color at the end of the game will score you points, as will having complete collections of all five colors.

Keltis is such a great game that the only negative thing I can think of to say about it is that it was only ever published in German. Even that isn’t such a bad thing as the file sections of BGG have provided me with very good English translations of both the base game and expansion. I like the game so much, in fact, that I actually prefer it over Lost Cities.

Keltis is Reiner Knizia at the top of his game. It’s one of those games that I am always happy to bring down off the shelf; it’s a joy for newcomers and experienced games alike. I highly recommend it.

This review convinced me to buy it on amazon.de. Thanks.

Fantastic. That’s one of our main motivations for publishing a review: could this convince you to buy (or not buy) a game.

Indeed. I don’t always comment, but love the reviews. Please keep up the great work!