Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

Ironwood represents a bit of a departure for Mindclash Games, publisher of such weighty and extended faire as Trickerion, Anachrony, and Voidfall. Ironwood is for two players. It lasts about an hour. It has only one rulebook, and that rulebook would make a lousy doorstop. While Meeple Mountain usually leaves Mindclash releases to Justin Bell—frankly, nobody else has the time to play any of them enough to write a review—Ironwood seemed like a good opportunity to let someone with fewer friends step up to the plate.

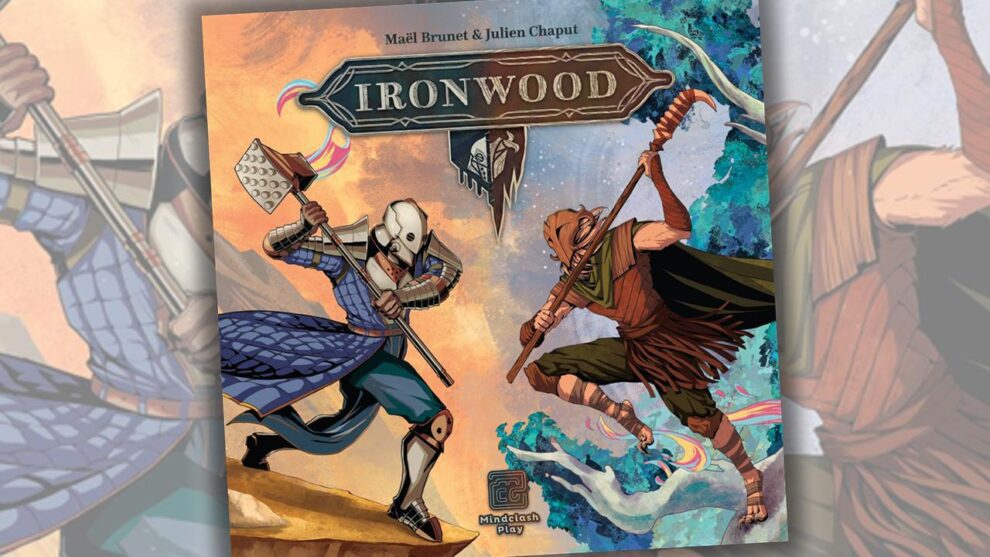

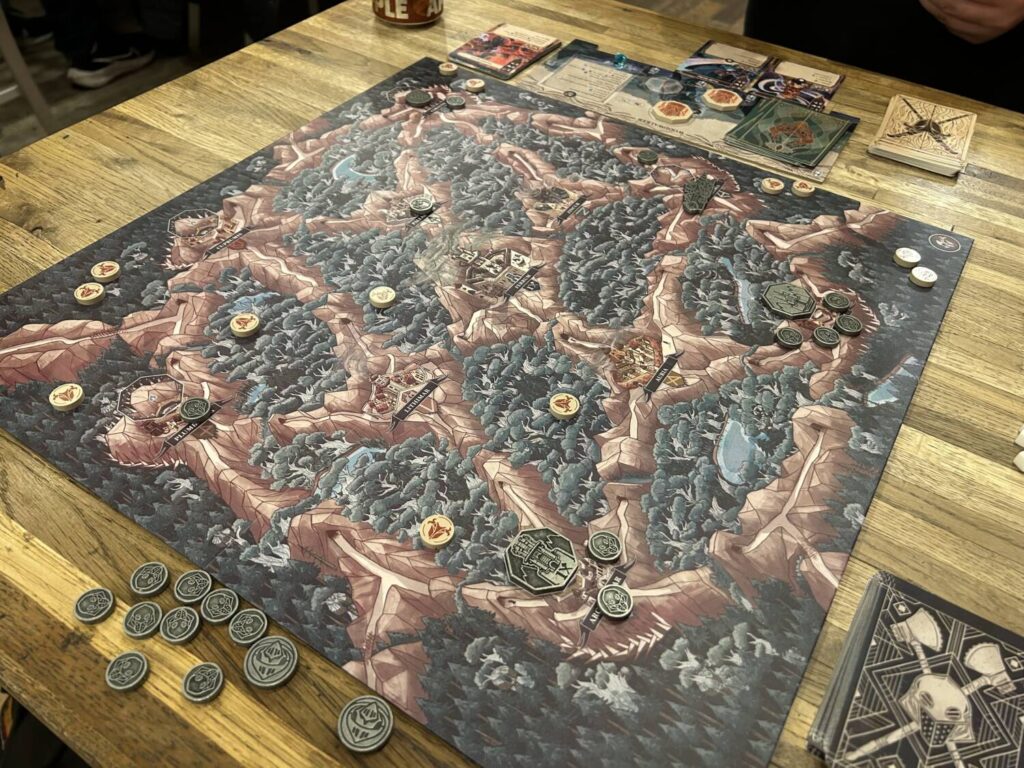

The whole of the premise is there in the title. Ironwood is about the clash between industry and nature, between the Na’vi and the Resources Development Administration, between Storm Troopers and Ewoks. It’s a tale as old as time, or at least 1977. The Ironclad and the Woodwalkers, as they’re called, vie for control of a heavily-forested mountain range. Or maybe that’s a heavily-bemountained forest. It’s hard to say.

Ironwood is a card-driven war-game, and specifically intends to be one that new players can approach without fear and that old pros will find engaging. The turn structure is nice and easy. The Woodwalkers play a card and perform the indicated action(s), then the Ironclad do the same. Back and forth it goes. The Ironclad attempt to construct three towers, while the Woodwalkers search the trees for three totems, which they then have to extract. If either player manages their goal, the game immediately ends, but it’s seldom that simple.

As you may anticipate from that cover, there’s a lot of fighting. Combat in Ironwood is smart. When combat is declared, each player plays a card facedown from their hand. Every card has three stats: Damage, Defense, and Control. The fight resolves simply: I deal damage to you based on my Damage value minus your Defense, while you do the opposite to me. Then, provided both armies have survivors—hardly a safe bet—the number of fighters in each unit is added up and combined with the Control value to determine the winner. This simple system borrows heavily from Kemet, which, why shouldn’t it? If you’re going to steal, steal from the best. Choosing what card to play in combat is a satisfying and harrowing decision point, rooted in fear of losing access to a card’s ability and in trying to guess what your opponent intends to do.

Every third turn, there’s a slight bit of maintenance. Each faction draws new cards, gains some of the crystals that serve as currency, and picks up any starting cards they may have played that round. The starting cards are one of my favorite design choices in Ironwood. Rather than give players a list of generic actions they can use on their turn, à la most GMT designs, Ironwood gives you three reusable cards, each of which features your faction’s basic actions. It’s a smart way to make the game more approachable for the uninitiated. Rather than spend half the game forgetting about the actions available to you outside of your cards, they’re right there in your hand.

The factions feel distinct. The Ironclad are slow and steady, working their way inevitably towards their goal. You rarely have showy turns, but you almost always manage to accomplish something meaningful. Meanwhile, your opponent can see you gaining on your goal, step-by-step, but it’s entirely possible they’re powerless to stop you. The Woodwalkers are guerrilla fighters, on the margins until they suddenly uncork an explosive turn or two. Both suit different temperaments of players.

As we’ve come to expect, Mindclash put tremendous energy into the production of Ironwood. Ironclad units are represented by hefty metal tokens, while the Woodwalkers are screen printed wood. The art on the cards, by Villő Farkas and Qistina Khalidah, succeeds in suggesting bursts of narrative. You find yourself filling in the edges of what’s shown, the foremost sign of terrific narrative art. My only complaint is that the metal tokens aren’t the easiest to see against the board. We can’t have everything, you know?

Like most card-driven games, Ironwood isn’t for the determinists. While it’s unlikely an entire game will come down to luck of the draw, a round certainly can, and if that happens to be the final round, well… The good news there is that the decks aren’t full of unique cards. You can learn both decks, become familiar with their strengths and weaknesses, and begin to engage with what your opponent seems well-positioned to do. Though I haven’t had the chance to do this myself, it seems entirely possible that Ironwood could reward repetition on a level close to its more involved cousins, War of the Ring and Twilight Struggle. I personally don’t find it compelling enough to put in that time, but I wouldn’t bat an eye if someone else did.