Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

The year is 1963. The steady hum of fluorescent lights fills your office at the 43rd precinct, where the morning paper screams of another killing in bold black headlines. Another body has been found, the third this month, and the press is calling it the work of the “Twilight Killer.” Each victim meticulously staged, each crime scene a twisted theater of clues, and each one had a motive.

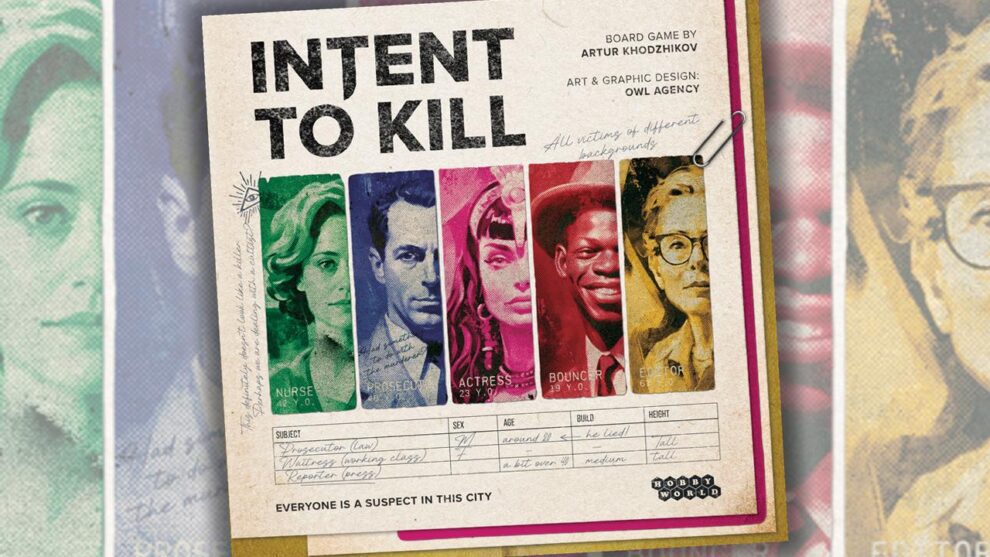

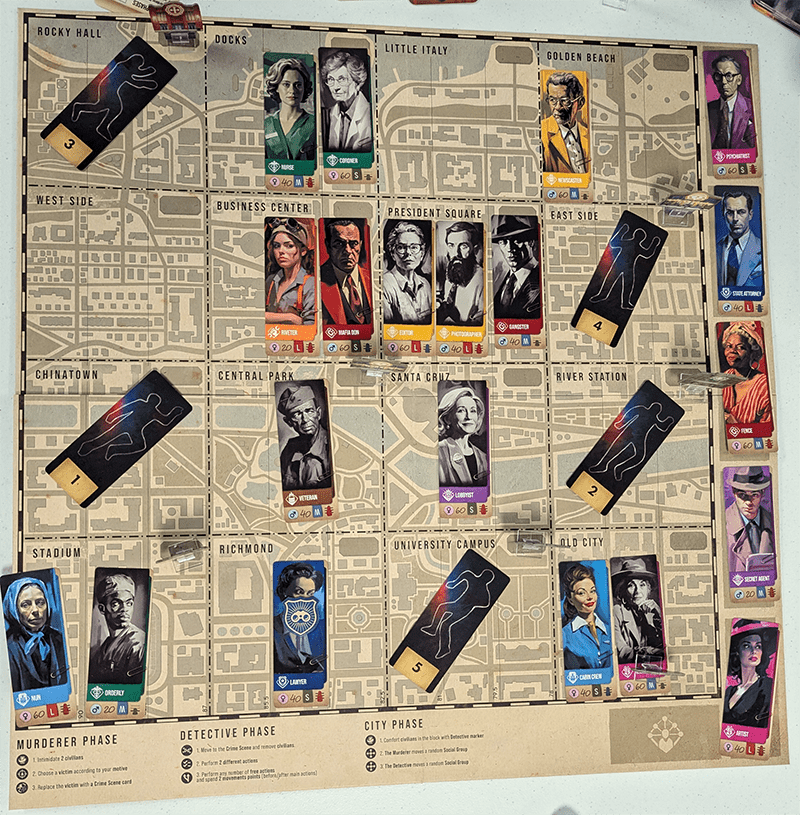

Intent to Kill is a two player game that pits the Detective versus the Murderer in a game of logical deduction. The game board, a grid representing city blocks, serves as the killer’s hunting ground. The Detective must identify which of the twenty civilians is the murderer and uncover their motive. The motive is one of six random cards and this motive enforces the conditions the Murderer player must follow to kill their victims.

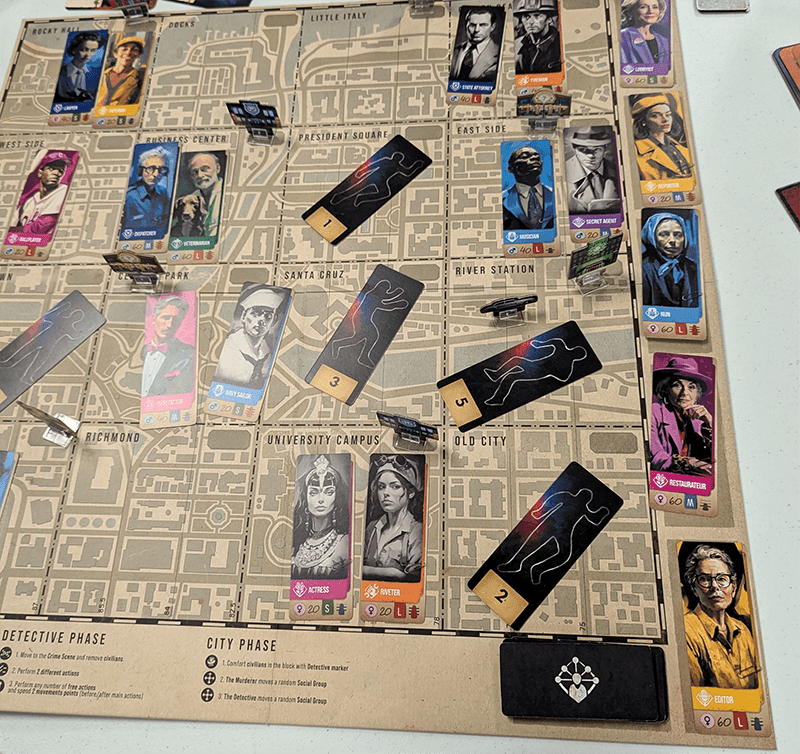

Conditions such as all the victims have been the same gender, all of them in different social groups, or no more than two different age brackets. Every civilian has several traits associated with them: social group, gender, age bracket, build, and height. By questioning the civilians, you can narrow down the suspect. By observing the victims, including where they died, you might see a pattern of the Murderer’s motive.

That’s the ground floor of Intent of Kill. As for playing the game, it’s amazingly simple. Not only are the vast majority of rules written on two player aids, there is also the list of phases printed on the board itself. It’s almost like the designer wanted people to play their game instead of “impressing” them with complexity.

Investigating the Inconsistencies

Each round is divided in three phases: Murderer, Detective, and City.

The Murderer phase lives up to the name, as this is where the Murderer acts. They intimidate two civilians, meaning those civilians cannot be questioned, and kill a victim while following the rules of their motive. The detective marker is then immediately moved to the new crime scene, while any citizens need to scatter to neighboring city blocks

From there, the Detectives come into play. They have two movement points to, you guessed it, move around the board. There are also two actions they choose from and they must be different. Four of those actions use a building type, assuming you are in a block with that building, while the fifth action is questioning civilians.

Questioning civilians is the beating heart that pumps the blood into this game. You question all the civilians in a block, asking them one specific trait of the serial killer followed by a simple yes or no answer. Was the killer a male? Was the killer in their 40s? Was the killer tall?

For the most part, the Murderer player must answer truthfully, and it’s here where things get a tad bit more difficult for the Detective. The Murderer has three distinct chances to deceive: they can lie when questioned directly by the Detective, through a special civilian marked as a Person of Interest, or by speaking as a member of their supporting social group (such as the Authorities or Medical Staff). As you can probably tell, it’s an uphill battle for the Detective, at least at first glance.

Dining Out

Each of the four buildings offers unique support to the Detective’s investigation. At the Diner, they can question any civilian in the same or adjacent block, offering the opportunity to do back-to-back questioning. The Hospital can calm down an intimidated civilian. By revealing a social group token at the Fire Station, the Detective can move civilians throughout the city – and notably, these revealed groups do not lie for the Murderer. The Police Station, while seemingly simple, often proves invaluable at crucial moments.

The Police Station permits the Detective to put a surveillance token on a civilian. This token can be used right away or later on, but the function is powerful. When activated, it forces the Murderer to reveal, without any chance of deception, whether their motive would allow them to kill that civilian. Used strategically, this direct information can help eliminate up to half of the possible motives in a single action.

Once the Detective has done their bit, the City phase takes the spotlight. Two social groups are revealed, allowing both the Murderer and Detective to move the social groups around. Most importantly, it also tells the Detective which social groups do not support the Murderer.

This cycle repeats for five rounds, representing the five murder victims. At the end of it all, the Detective has one opportunity to guess the suspect and motive. If the Detective is correct, they win, otherwise the Murderer disappears into the night with their crimes remaining unsolved.

Cracking the Case, or Lacking the Clues?

As a fan of deduction games, especially as a player that often takes on the role of the “one” player in a one-vs-all game, Intent to Kill is one of the simplest deduction games I can introduce to people. The majority of actions are easily explained in a sentence or two, with the only complications being the conditions the Murderer can lie to the Detective. Otherwise, once the rules are figured out, the rest falls into place with ease.

From there, the game feels like a Sudoku puzzle that despises your existence. Both the Murderer and Detective have to follow strict logical rules and utilize them to outsmart their opponent. Insert chess metaphor here.

From the Murderer’s perspective, who they murder and where become vital pieces of meat for the Detective to chew on. The optimal play here is to make sure your victims land on several motives at once. If the potential six motives involve killing people alone and all your victims have to be one gender, start murdering all the males alone in a block. Keep them guessing and force the Detective to waste their precious actions on the Police Station instead of questioning the civilians.

Questioning civilians is another crucial battleground where both the Detective and Murderer seek to gain an edge. The Detective aims to question as many different people as possible, while the Murderer attempts to steer the Detective towards the wrong civilians.

The Murderer has two key methods to achieve this. First, when a murder occurs, the Detective marker is relocated to the new crime scene, potentially limiting them to questioning civilians willing to lie on the Murderer’s behalf. Secondly, the Murderer intimidates two civilians per round, shutting off those potential leads. Astute Detective players may even discern hints about the Murderer’s allies based on intimidated civilians.

When the Evidence Doesn’t Add Up

All this sounds fantastic, and for the first few plays it was. Like all of my reviews, I play games often to see if their designs hold up, and Intent to Kill doesn’t always hit that mark. It’s good, but could’ve been better.

Everything I described about the strategies and tactics regarding the Murderer and Detective are the same in every session. The Murder will always kill targets that fall into several motives while relocating the Detective to a block where their turn is unproductive or worse, misleading. The Detective reacts by questioning civilians and doing some cross-examination in order to enact the process of elimination. Building actions are used to further compound the elimination, such as the Fire Station, to remove social groups supporting the murderer or Police Station to narrow down the motive.

The central issue with Intent to Kill is it tries to be a detective story without the story. The core elements – the murder suspect, person of interest, motive, and supporting social group – are all randomly determined, rendering the classic “red string” of deductive reasoning to be a myth here.

The civilians themselves lack any distinct personalities or narratives, serving merely as vessels of statistics, numbers, and social affiliations. This means that seemingly nonsensical pairings, such as a cannibal Mayor as the murderer, the Cat Lady as a person of interest, and the medical staff secretly supporting the Mayor, can occur without any coherent thematic logic.

Intent to Kill seems to acknowledge this issue because they have scenarios with a special rule or two, and an Intuition mode. Everything I described so far is the Logic mode, and Intuition adds more tools for both sides to use.

Blurring the Lines Between Logic and Intuition

Intuition provides both the Murderer and Detective with special deck-drawing abilities. These cards allow them to enact powerful effects, such as forcing an entire city block into silence or directly interrogating the Murderer about their motive without any opportunity for deception. While not the most creatively game design approach, this Intuition variant does at least inject a higher level of complexity into its veins that somewhat compensates for the baseline narrative incoherence.

Does this make Intent to Kill a bad game? Absolutely not. As a critic, it’s my duty to highlight perceived issues, but I can’t ignore the game’s widespread appeal among my peers. This is an exceptionally accessible title with a frictionless set of rules set that anyone can glide on.

While it may not unseat the titans of hardcore deduction gaming like Detective: City of Angels or Tragedy Looper, Intent to Kill doesn’t need to. Its shortcomings in narrative coherence are simply a compromise, and the game still manages to deliver a satisfying investigative experience – one where the clues may not always lead where you expect, but the thrill of the hunt remains ever-present.