“Kingmaking” is a term that gets bandied about in board gaming circles, often with a snort of derision. It refers to a state within many board games where a player who is not in the running to win the game gets to make a decision that ensures (or makes pretty darn sure) that another player will win; thus, kingmaking.

This occurs in many games, and can generate soreness around the table. Kingmaking can often break immersion. If we’re playing a game where we’re big noble space empires fighting over a map, and someone’s choice of a “culture card” or an “auxiliary action” causes the dominant player to lose the game, that takes you out of what can be a powerfully immersive experience.

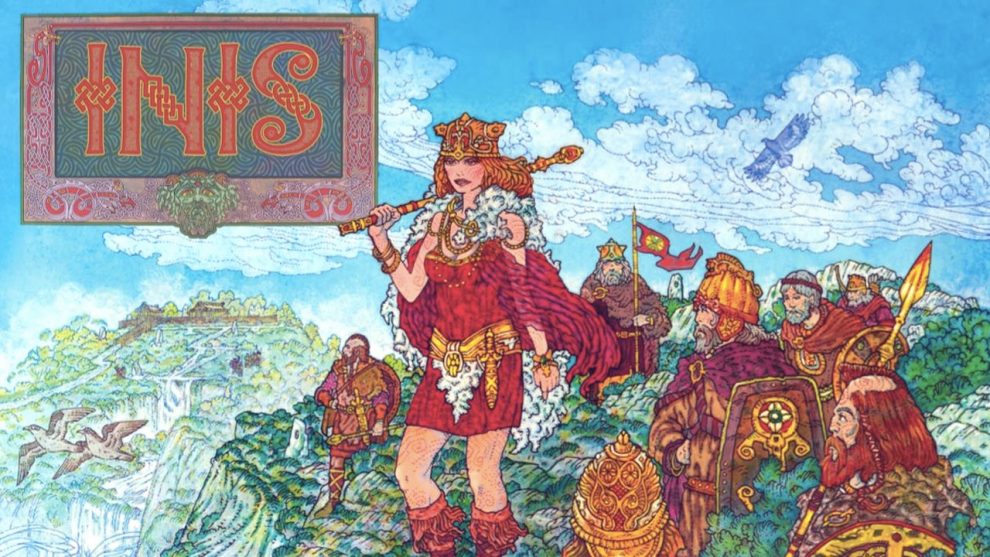

Now, Inis (pronounced in-ish) is a fantastic game, because it takes the kingmaking problem and explicitly makes a game about making a king, though not exactly in the way you might be thinking.

Let’s Be Pretenders to the Throne

Inis is a deep game. It’s a deep game about power struggles, and it’s one that makes a very interesting statement about them. 2-4 players are competing to become ruler of the island, and each player is a pretender to the throne. I’m not going to dive too deeply into the specifics of the rules, but I will outline the three different victory conditions with some granularity.

Two of them revolve around having board presence:

- A player has units present in at least 6 different territories.

- A player has units present in territories with at least 6 sanctuaries (a type of building in the game).

The other requires dominance:

- A player is considered “chieftain” of a given territory when he has more units there than any other player. Be chieftain over 6 of your opponents’ units, and you have satisfied another victory condition.

These conditions do not in themselves win you the game. Each time you accomplish 1 or more of them, you can take a pretender token, which allows you to win at the start of the next round, provided you don’t tie with another player for most total victory conditions. Unless that player is the Brenn, a player who is chieftain of the capital territory. That player can win in the case of a tie.

Hopefully, I didn’t lose you through that, because those specifics are important to know to understand why the game is interesting. Inis is about determining a ruler, and the fundamental premise of this game is a good ruler understands that timing is everything. Inis is not just about fielding massive armies and smashing your opponents; it’s about outsmarting them and outmaneuvering them—because, oddly enough, this is a game with fighting that believes that fighting is bad.

Savvy is Sexy

Play is driven by drafting cards (leaving you with a hand of four) and then playing these cards to change the board state in the main phase of the game. Cards in Inis will do everything: adding to the map, moving units, making a territory a safe space, adding buildings, and more.

On your turn you can play a card, pass, or take a pretender token if you meet a victory condition. But remember this doesn’t let you win until another phase, so other players can potentially take your hard-earned victory condition away.

STOP.

One of the most common criticisms of this game is that if everyone is good enough, it never ends. You can respond to each other in perpetuity. This is a poor criticism, because it forgets that this game is about timing, and that you can pass. Passing does not forfeit the rest of your actions unless everyone else passes, which would end the round. If other players keep going, you get to jump back in once the round comes back to you. Passing gives you hand advantage, and it gives you a timing advantage. You now are better positioned to make good moves!

Bad games of Inis are thematically appropriate, funnily enough. I’ve seen games with four players where nobody passed, and just kept responding to each other, smashing armies and swapping control of territory with nobody getting the lead. Inis is saying that this is a bad way to find a ruler–squabbling despots only lead to more death and don’t let people get on with the business of living under some sort of organized system.

Epic Tales and Farcical Fights

There are several components of the game I am glossing over in this review, not because they are bad, but because in evangelizing for this game, I have to focus on what it’s about— getting overly bitty about the bits will distract from what’s cool.

Fights are ludicrous and make everyone suck air between their teeth. Units can share the same space and do not necessarily have to fight. In a fight, when a player is attacked, they have to choose between losing a unit and losing one of their action cards. Both are horrible, and lead to some remarkably catty table talk.

There are also Epic tale cards, which are like superpowered god-mode versions of the other cards that you can hold between phases. When somebody piles up enough of these, they can chain together and win the game.

So Inis is not about bashing each other over the head–it’s about watching your opponents closely, seeing when they are weak, and jumping in to win. Bluffing is a big part of it; playing dead is another. Attacking when you know somebody is about to plan some big moves is both savage and delightful.

Of Art and Groupthink

Board gaming is inherently a consumptive industry. There are too many games, too many of them are OK enough to buy, and it’s hard to tell what you will like. Inis is an undeniably beautiful game, with art by Jim FitzPatrick, world-class artist (and creator of the famous Che Guevara poster). All of that art, and all of that promise, makes a claim about what it is trying to be: a game about how to wield power in an intelligent, meaningful way. It’s a deep and thought provoking experience that you will think about when you’re not even playing it. Inis knows exactly what it is trying to be, and in my opinion it proves that it is what it’s claiming to be, which you can’t say of very many games.

Get out there and try Inis! That is, if you’re like me, and think about power, and how we’re supposed to deal with it. Hopefully you and your friends can find a leader instead of a despot.

Add Comment